The Columnists : These Days, They Jump Teams, Earn Big Money and, for Better or Worse, Write Their Own Ticket

As the year began, commercials heralding “The Move” appeared on Dallas television screens. A big sports celebrity was about to change jobs.

The use of such prominent Dallas sports figures as Cowboy receiver Drew Pearson, Texas Ranger Manager Doug Rader and Maverick basketball Coach Dick Motta in the commercials led to the suspicion that it was someone the stature of, say, Tom Landry or Tony Dorsett.

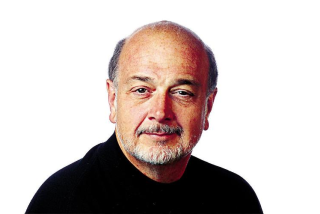

It was. Blackie Sherrod, the fellow making the much-publicized move, is as well known in Dallas as the Cowboys’ coach or their star running back. But Sherrod is no athlete or coach. In the commercials, in fact, he sat behind a desk in the back of a moving van, typing away on a computer terminal.

Remarkably, all the fuss was over a sportswriter who was moving his column from one newspaper to another in town. As Sherrod passed through the streets in the truck, pedestrians Rader, Motta and Pearson looked up in surprise and did double takes.

Sherrod, 65, has been writing columns since 1948. He is as popular in Dallas as Nieman-Marcus, and his move from the Dallas Times Herald, where he had been a fixture for a quarter of a century, to the rival Morning News was big news.

Dallas is one of the few cities where such a fuss would be made over a sports columnist. The competitiveness of its newspaper market is rare in an era when one paper is usually either dominant or the only one in town. Hildy Johnson probably would just as soon work in a bank today. There are no more “Front Page” wars.

Still, Sherrod’s move was not unusual. In recent years, sports columnists have been changing newspapers about as frequently as baseball teams change managers and, surprisingly, some have moved up to six-figure salaries. For a working newspaper stiff, a salary exceeding $50,000 is unusual and one of $75,000 is as rare as a no-cut contract.

Although some papers have hired the best established columnists money can buy, others have gone out of town to recruit top feature writers and reporters for the job. San Diego papers, to give you an idea, brought in a columnist from Philadelphia and also brought in a reporter from Washington to be a columnist. Alan Greenberg of The Times was recently hired by the Courant in Hartford, Conn. The Detroit Free Press recruited in Chicago, the San Jose Mercury in Cincinnati, the Chicago Tribune in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

All this shuffling of talent has raised salary levels for columnists on large papers to an average of $46,700. Two years ago, the average was $32,000.

Some are earning more than $75,000, and at least three--Sherrod, Dick Young of the New York Post and Skip Bayless of the Dallas Times Herald--are making more than $100,000. Some writers have been given financial-incentive packages and others such perks as country-club memberships and company cars.

There seems to be no dominant reason for this surprising trend. Columnists have long been the stars of the sports department, but until a few years ago there were few examples of management fighting to keep one. If a columnist quit, another writer on the staff usually moved into the job. After all, sports was the toy department.

A column once was chiefly a local thing. Hardly anyone outside his home town ever heard of a columnist from Dallas or Denver. In the 1920 and ‘30s, such famous names of journalism as Westbrook Pegler, Paul Gallico, Grantland Rice, John Kieran and Damon Runyon wrote sports columns, but for many years after World War II about the only nationally known sports columnists were Jimmy Cannon, Red Smith and Jim Murray.

“There are two kinds of sportswriters: those with good sense and the ability to go on to other things, and those with neither,” said Leonard Shecter in his book “The Jocks.” Pegler, Gallico, Runyon and Kieran went on to other things.

But there are today, working in sports departments across the land, a group of hugely talented columnists who write with as much skill and perception as anyone in the newsroom. Why suddenly, after all these years, are they in such demand? What is their appeal? Do they sell papers? Are they earning their big salaries?

“We’re a star-oriented society and (publishers and editors) must think a star builds circulation,” The Times’ Jim Murray said. “They say (gossip columnist) Walter Winchell used to sell papers in New York, but I really don’t know if a sports columnist sells papers. I think the readers would miss him--but maybe not for a long period.”

Said Dave Anderson of the New York Times, one of only three sportswriters to have won a Pulitzer Prize: “Some sports columnists sell papers in some towns. I don’t think my column is a big factor in the Times’ circulation.”

Hubert Mizell of the St. Petersburg Times in Florida said: “If I left my paper tomorrow, it would lose one subscriber--me. But I think I add to the overall quality of the paper.”

Said Mel Durslag of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner: “One guy can’t make a difference on a paper except in rare situations where there are dogfights for circulation.” He added, however, that the cumulative effect of hiring quality writers can make a difference in other towns.

“The quality of a paper’s product would suffer if its star columnist leaves,” said Dave Kindred, once the star columnist for the Washington Post who recently left for the Atlanta Constitution.

Kindred believes only two columnists sell papers today: Young of the New York Post, who was wooed away from the New York Daily News a few years ago, and Murray of The Times. Of Young, Kindred said: “He is gritty, has opinions, and people read the Post to see what he has to say.” He called Murray unique, imaginative and fabulously funny.

In the view of the Washington Post’s Tony Kornheiser and others, the only three papers that don’t depend upon a sports columnist to boost circulation are the New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, which successfully market the excellence of their entire editorial package.

“I feel I do sell some papers,” said Bayless of the Dallas Times Herald. “Dallas is a cutthroat, competitive situation. They keep talking about a war. They have marketed sports columnists as controversial.”

Sherrod said: “A columnist can’t make or break a paper but he can help one. Most of us have an exaggerated idea of our own importance.”

Art Rosenbaum, a columnist for 47 years at the San Francisco Chronicle, said he doubts if a sports columnist can increase circulation. In fact, Rosenbaum doesn’t believe any single writer can carry a newspaper.

Herb Caen, the Chronicle’s popular general columnist, was generally believed to have the most circulation clout when he jumped to the San Francisco Examiner in 1952, then back to the Chronicle in 1960. Rosenbaum kept a record. In the eight years Caen wrote for the Examiner, he said, its circulation increased by 58,637. In the same period, however, the Chronicle’s rose 124,000 without him.

“As big as Caen is, he was not as big as the paper itself,” Rosenbaum said.

Said Burl Osborne, president and editor of the Dallas Morning News: “In terms of having a complete newspaper, the sports columnist is very important. The circulation department has a much easier time selling papers because of them.”

Probably no paper markets sports as aggressively as the Philadelphia Daily News, which recently hired John Schulian, late of the Chicago Sun-Times, as its fourth columnist. Street sales account for 80% of the paper’s circulation, and on Mondays after the Eagles win, circulation goes up about 10,000, Managing Editor Tom Livingston said. The day after the 76ers won the National Basketball Assn. championship in 1983, the Daily News sold an extra 80,000 copies.

“We’ve been aware of Schulian’s writing for years,” Livingston said. “He’s one of the best. Good sports writing is a tradition with us. It can mean direct sales.”

By all accounts, the Daily News publishes some of the best sportswriting in the country, but its circulation is only 295,000. Its rival, the Inquirer, sells more than 500,000. Newspapers cannot live on sports alone.

Still, there is little doubt that the sports columnist has a strong appeal. Why not? Sports is a major segment of any newspaper. It is as important to sales, probably, as international, national, local, entertainment and business news. There is a growing interest in sports, stimulated by television and the increased leisure time and affluence of fans.

“Newspapers are responding to this new level of interest,” said Phillip L. Williams, senior vice president, newspapers and television, for Times Mirror, which publishes the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Times Herald, Denver Post, Newsday and Hartford Courant. “Sports has taken a position a little higher in the ranks.”

For the readers of a good newspaper, columnists are a fringe benefit. Their essential function is, in 800 or 900 carefully crafted words four or five times a week, to inform, entertain and bring to readers an understanding of the news. The best ones do it with a light touch because, the Nashville Banner’s Fred Russell said, “Laughter cheers the soul.”

Good columnists are opinionated, which is a good thing because their readers are a highly informed bunch who view themselves as authorities and delight in matching their views with the writers’. Wise columnists learn early that it is not easy to fool readers.

An adversary role is useful but not necessary. Empathy and fairness are two of a columnist’s most important tools, and, if he lacks those, he’d better take the time to be brief. Triteness is to be avoided, and self-boredom, Russell said, “can be poison.”

Jimmy Cannon once said: “The worst thing a sportswriter can be is a fan.” Virtually all of the columnists interviewed for this story said that they enjoy their work and that they like sports but are not fans. Prestige, recognition and the freedom to write what they please are the things they like best about their jobs, they said.

Said Livingston: “People enjoy more than a description of a game. They want another view, something they can sink their teeth into. Sports columnists are there because they are read.”

Dave Smith, sports editor of the Dallas Morning News, agreed. “No sports section can compete without a columnist,” he said. “Readers are no longer content with reading about a game. They want opinions because they have them. That’s the fun of sports.”

Jim Murray remembers when, as a reader, he wanted to know what the columnist had to say about a championship fight. “I knew who won it,” he said. “I wanted to know what Bob Considine or Jimmy Cannon thought about it.”

Anderson of the New York Times made a similar observation. “Readers want to see what I have to say that day,” he said. “A reporter is not saying anything; he doesn’t have that freedom.”

Murray was a reporter and feature writer for Sports Illustrated when The Times hired him as a columnist in 1961. The prestige of his new job appealed to him, he said. “If you feel you’re a good writer, it is the ultimate showcase for it. It’s the top of the line.”

On his style, Murray said: “I always try to entertain rather than inform. I write about people.”

Nothing pleases Kindred more, he said, “than having a lot of great facts and forming an opinion on them.” He does it in a style that is “light, critical and opinionated.”

Kindred has a strong feeling for the games and people he writes about. “I see greatness in sports,” he said. “I see human excellence.” He tries to make his readers feel what he feels. “I evoke strong emotions--anger or whatever,” he said. “I try to move people. If I’m mad or happy, I want them to share it. I try to give them some views and news and make them smile.”

Anderson, whose style is simple, quiet and graceful said: “Basically, I write about people. If you don’t like people, what do you write about, the ball? I don’t think you have to save the world every day. You can have a viewpoint without having a strong opinion. There are not many stands worthwhile in sports.”

The Washington Post’s Kornheiser said: “For a natural columnist, a column is a forum for his opinions and ideas, and a chance to have influence on the community.

“It is a tradition of our business that the column is a paper’s way of saying, ‘This is our best writer.’ ”

To Kornheiser, a natural columnist is one “who can articulate his opinion, consider the other side, then reject the other side with his column. Jim Murray is one. I am not.”

Kornheiser, in fact, would rather write a good feature story than a good column but said: “Columns pay. How can you avoid listening to six figures?”

Pete Axthelm is a sports columnist for Newsweek magazine, which frequently uses his writing skill on news stories. He recently covered the New York vigilante story, and he finds nonsports assignments more satisfying. “I had more reaction to my vigilante piece than any story I’ve ever done,” he said. “But it is easier to write a column because you can substitute opinions for reporting.”

The appeal of a column to Bayless is the lift he gets from writing one. “A column gives you gratification immediately,” he said. “People want to know what I have to say, my sports editor tells me.”

To Durslag, a column offers more latitude for editorializing. “It’s opinion. You hang it out there for better or worse. You have more directions to go. You can be light or serious.” His job, Durslag said, is to offer more comment and observation than quotes. “I don’t see a columnist as one who goes into the locker room.”

Rosenbaum said: “Certainly ego is involved,” and cited the ability to express thoughts freely as appealing.

Money is part of the appeal, “but not all of it,” for the Miami Herald’s Edwin Pope, who puts the freedom of the job ahead of everything else. “It is a good feeling to create something of my own without being told what to do,” he said.

To Mizell the appeal is in the recognition. “People identify with a columnist,” he said. He also feels pressure, though. “Your head is on the chopping block five days a week,” he said. “It is the power position on a newspaper, the job everybody is shooting for.”

Said Bob Hurt of the Phoenix Republic Gazette: “Essentially, you must have a reasonable subject and a thought to express--yours or somebody else’s.”

Hurt said he may not have the appeal of some columnists because he is not controversial. “I am from the old school,” he said. “I like to talk to athletes and quote them. I realize that is not the role of a columnist today. I’m in the minority. What bugs me is the guy who goes out to create a controversy. To do it to attract attention bothers me.”

Columnists are sensitive to their adversary roles and most of them resent, as Hurt does, those in their business who deliberately stir up a fuss to attract attention.

There is more harsh commentary today because many columnists are young--the Dallas Morning News marketed Bayless as a celebrity when he was only 26--and in an attempt to impress their contemporaries by exposing all the evils of sports, some substitute controversy and confrontation for perception, knowledge and experience.

Sherrod calls them slashers and blames their hard-hitting style on Watergate. “I’ve never been a slasher,” he said. “I don’t take sports that seriously. They are not that important.”

Anderson blames the hostility of young writers on inexperience. “You shouldn’t be a columnist at 26,” he said. “You haven’t been around long enough to have the perspective a columnist is supposed to have. A lot of guys could be very good columnists if they waited five or 10 years.” Anderson was a reporter long before he got a column.

Anderson also said that many of the angry young columnists today don’t like sports. “You should enjoy them if you’re going to be a columnist,” he said.

To Anderson, conflicts between newspapers and sports, are inevitable. “We are natural adversaries,” he said. “You should disagree once in a while. Some teams think papers are an extension of their P.R. departments.”

Murray also sees evidence that Watergate influenced some columnists. “There is a tendency to take a sour attitude in all of journalism,” he said. “It’s Watergate. Everybody wants to become famous.”

Murray became the most famous sports columnist in the country by having fun with the events and people he writes about. Hyperbole, literacy, humor, similes and a deft needle are his staples. He saves his anger for injustice. As the late Red Smith might have said, innumerable rabbits have bared their fangs trying to replace Murray. None has succeeded.

“A lot of columnists resent sports,” Kindred said. “They think they should be doing something more important. When you don’t have an idea, it is easier to find fault.”

Kindred doesn’t pick fights, he said; he just doesn’t avoid them. “If there is a public controversy, it’s the columnist’s job to take a side. That’s a lot different than creating one. Columnists with that style are shouting to be heard. You see more cynical, controversial columns on sports than anywhere else. Perhaps that’s a reflection on sports. There are a lot of good columnists. What bothers me most is, I don’t think there are a lot of good reporters.”

Bayless said he has an adversary relationship with all teams. “It’s difficult,” he said. “I struggle with it. But readers want the truth. They trust me to tell them what’s really going on at SMU, at Texas, or with the Rangers and Cowboys.”

In Durslag’s view, columnists’ styles change over the years. “The attitude now is to hit ‘em hard; don’t hold back your punches,” he said. “That’s all right, but if you go looking for people to stick as a daily fare, you’re going to make mistakes.”

Durslag, alluding to his fight with Commissioner Pete Rozelle over the treatment of the Raiders by the National Football League, said: “I’ve been called (Al) Davis’ hatchet man for years. That’s not typical of my work.”

Young columnists today are mostly decent, incorrupt people, Durslag said. “They pick fights for fear they’ll be called a house-man. Humor is not part of their styles. They say, ‘Hey, look at the number I’m doing on this guy.’ They want the focus on themselves.”

Pope has been writing about games for 45 years and said it took him 40 years to learn how--”If I have learned.” He said: “A lot of young columnists try to make a name by being mean, and sports are not important enough to be mean about.”

Michael Novak, who wrote “The Joy of Sports,” sees in today’s sports sections a “rage against sports. There is a virulent passion for debunking in the land. It seems astonishing to read writers who do not love their subject.”

Sportswriters aren’t the only critics who rap the events and stars they cover, of course. Trenchant commentary abounds on pages devoted to the arts, music, movies and television. A critic named Percy Hammond once said in a review of a musical comedy, “I have knocked everything but the chorus girls’ knees, and God anticipated me there.”

While some papers pay a premium for quality writing of all kinds, most give the highest salaries to columnists. Are they worth it?

“I don’t know if I’m worth my salary or not,” Bayless said. “I guess I am, because someone is paying me. Is it justified? I don’t know.”

Kindred wasn’t sure, either. “It is hard to justify in (circulation) numbers,” he said. He moved to Atlanta for less money than the Post paid him but got “an imaginative package of financial incentives” and the prospect of becoming an editor.

Anderson said his business is “the most underpaid business in the world.”

Kindred has an idea why. “Newspapers are made up of young people who think they’re going to change the world,” he said. “They are dreamers and idealists. They will work for nothing for a byline. Too many people, in fact, have worked too long for too little money. It’s not a case of me being overpaid. It’s a case of editors being underpaid.”

In an extraordinary session at an Associated Press convention last November, Bayless, Kindred and Schulian were put on stage by the editors and asked to defend their salaries. The writers, Schulian said, were like lambs in a lions’ den. “I would be kind of curious to see if three of you would come to a room full of sportswriters to defend your salaries,” he told the editors.

Cannon often said: “A sportswriter is entombed in a prolonged boyhood.” To columnists, however, the job is not all fun and games. Kornheiser, accustomed to writing 5,000-word features two or three times a month, said: “It is damn hard. The space is being held. You can’t take another day. They’re putting your name in lights.”

Deadlines affect Kindred the most. “You feel you’re always compromising and taking a shortcut,” he said. “You don’t have enough time. You seldom write a sentence the way you want to write it.”

Bayless has trouble coping with the mental burden. “The column is seldom out of my thoughts,” he said. “It hasn’t been good for my personal life. It wrecked one marriage and one serious relationship. I don’t take myself seriously, I take the job too seriously.”

The hardest part of the job for Sherrod is finding a good subject. “And the travel is difficult,” he said. “It seems the older you get, the more you travel.”

Pope finds that a negative, too. “The travel is hard on my family,” he said. “I was on the road 37% of the time last year.”

Although he usually writes five columns a week, Pope wrote more than 30 straight as the Miami Dolphins made their way to the Super Bowl. At San Francisco last month, he said: “It’s hard to lock yourself in a hotel room. That’s all I see here.”

For Anderson, the actual writing is difficult. “I don’t like writing,” he said. “It’s a struggle. You like it when it’s done. It’s like climbing a mountain.”

As for ego, would-be columnists can learn from Fred Russell that a columnist can go downhill fast. After writing 18,000 columns in 51 years, Russell was approached by an elderly woman who told him, “Every column you write is better than the next one.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.