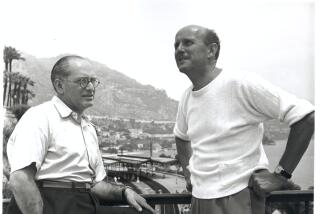

Philip Scheuer, Ex-Times Film Critic, Dies : Witty, Gentle Writer Bridged Eras of Silent and Talking Movies

Philip K. Scheuer, The Times’ film critic for the first four generations of the sound era, died Monday at Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center after a brief illness.

Friends said Scheuer, who would have celebrated his 83rd birthday next month, had been in declining health for some time and was hospitalized after suffering a heart attack two weeks ago.

Witty, literate and a lifelong exponent of good taste in motion pictures, Scheuer began his career at The Times in the early 1920s and was believed to be the last of the critics who had reviewed both silent and talking films.

Born March 24, 1902, in Newark, N.J., Scheuer was the son of a grocery executive and entered the motion picture industry as the result of winning a high school contest.

“The first prize,” he told a friend in later years, “was a trip to Hollywood to interview people in the movie industry. After that, there was simply no chance that I would ever go into any other line of work.”

‘Silents Were Doomed’

Nonetheless, he said, he was unable to find steady employment in the movies and so went to work in The Times’ entertainment department, becoming second assistant film and drama critic in 1927, the same year “The Jazz Singer” broke the silence barrier.

“Some silent films were made after that,” he recalled. “But by the time Warners released its first all-talking film (“Lights of New York”) in 1928, it was obvious that silents were doomed. . . .”

Scheuer chronicled the metamorphosis and labored with dogged determination to help establish motion pictures as a separate and valid art form rather than as a mere commercial adjunct to the performing arts.

“Unfortunately,” said Charles Champlin, who succeeded Scheuer in 1967, “he was The Times’ principal film critic in a time when no one thought there was any sensible film criticism west of Manhattan Island--and also at a time when, to be frank, The Los Angeles Times had a reputation for prosperity rather than editorial greatness. So he was much undervalued as a film critic.

‘Fair and Eloquent’

“Re-reading his clips, however, you see what a very, very good critic he actually was: knowledgeable, fair and eloquent.”

Another problem of the early years, Champlin recalled, was that Scheuer was required to turn out a daily column of movie gossip in addition to handling most of the critical chores.

“It was a real strain over the years,” a friend recalled, “to be constantly interrupting serious critical efforts in order to churn out something about who was seen with whom. He did it with little or no complaint--but he hated it.”

Scheuer’s efforts did not go entirely unappreciated, however.

His fairness and unfailing courtesy made him the friend of the great and near-great of the film industry--regardless of his published appraisal of their efforts--and longtime friend Walter Seltzer called him “the best friend of a neglected species: the movie press agent.

“He was incorruptible. You quickly learned never to lie to him or try to buy or bulldoze him. But through it all, he was always gentle, polite and pleasant. I don’t think there was a mean or ugly side to him. At least, no one I know ever saw it.”

In addition to his work for The Times, where he succeeded Edwin Schallert as motion picture editor in 1958, Scheuer was also film reviewer for Family Circle Magazine and sold numerous articles for such national magazines as Colliers and Saturday Evening Post.

An ‘Important Factor’

In addition, he was a frequent guest lecturer at university film classes.

In 1959, the Screen Directors Guild presented Scheuer its sixth annual Critics Award, citing his “constructive and enlightened criticism” as an “important factor in encouraging higher standards in motion pictures.”

He retired in 1967, and friends said he was not entirely unhappy to do so.

“He wasn’t happy with the way things were going,” a friend explained. “The new system that permitted smut a certain respectability by allowing it on screen with an ‘R’ or ‘X’ rating, and the universal grubbiness and bad language that characterized the supposed ‘new freedom’ in film, was anathema to a man of taste and breeding.

“He hated it.”

Scheuer’s wife, former Busby Berkeley dancer Constance Marie Kraus, died in 1962. He is survived by a daughter, Lucie Scheuer.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.