POP MUSIC : Hard-Core Softies : Orange County punk-rockers Offspring dish up anarchy with a playful (and somewhat polite) attitude.

‘It was fun, it was rad, it was really cool,” says Offspring singer Bryan Holland.

It’s been a year of highlights for the band, but the four members seem especially excited about having opened the Fox network’s telecast of the Billboard Music Awards last month.

Orange County punk-rock bands don’t generally appear on high-profile live specials, and when Holland recalls his sudden stage-dive into the unsuspecting Universal Amphitheatre audience, his band mates utter spirited exclamations of admiration.

“At our regular shows there’s a bunch of skater kids in front,” Holland explains. “At this show, since we were playing with Warren G and Melissa Etheridge and stuff, there were all these people in nice evening gowns in the front, and I don’t think they were really expecting me to dive on their heads.”

Holland’s surprise maneuver was pretty much the same thing Offspring did to the music business in 1994.

The unknown quartet from the Garden Grove area released its third album, “Smash,” in April on the independent Epitaph Records label. By year’s end, it had sold an astonishing 3 million in the U.S. and 5.2 million worldwide, becoming the biggest-selling rock album ever released by an independent label (one not affiliated with the six major conglomerates that dominate the industry). Even friendly rival Green Day, ‘94’s other big punk-rock breakthrough band, had the benefit of a major label behind its 3 million-selling “Dookie” album.

The theories poured in. The success stemmed from the music business’ new marketing and distribution realities. It was a lucky stumble into a vast audience primed for the hard stuff by alternative-rock’s advance. The band somehow gave voice to young fans’ rising mood of disaffection.

What do the perpetrators think?

“I don’t know,” says Holland. “We just tried to write the best songs we could. Looking back on it, you know, they are kinda catchy.”

*

For years, the terms catchy and punk rock coexisted about as well as Newt and Hillary.

Exploding into a moribund rock world in the mid ‘70s, punk rock reacted against the values of virtuosity and broad appeal, signaling its defiance with abrasive textures, tuneless singing and warp-speed tempos. But inevitably, musicians bristled at punk’s orthodoxy. New York’s Ramones and England’s Clash and Buzzcocks, among others, expanded the horizons with an affectionate embracing of commercial-pop and roots-rock strains.

In Orange County, early-’80s grass-roots bands started harnessing punk’s energy to the region’s surf-music tradition and buoying it with melodic pop elements. Independent records and live club shows by Long Beach’s Vandals and T.S.O.L., Fullerton’s Adolescents, Social Distortion and Agent Orange and Cerritos’ Channel 3 escorted kids like Holland and his friend Greg Kriesel through adolescences of middle-class ennui and misfits’ insecurity.

Now that they’re in the driver’s seat, Offspring is opening things up even more, bringing in instrumental hooks, vocal chants and a wide variety of tempos and textures.

“Early punk rock was like a burst of expression, but they didn’t worry too much about things like songwriting, I don’t think,” says Holland, who writes all of Offspring’s songs. “I think we’ve tried to take the elements of punk rock that we like and try to use it with real songwriting. . . . Try to make it what you might call listenable.”

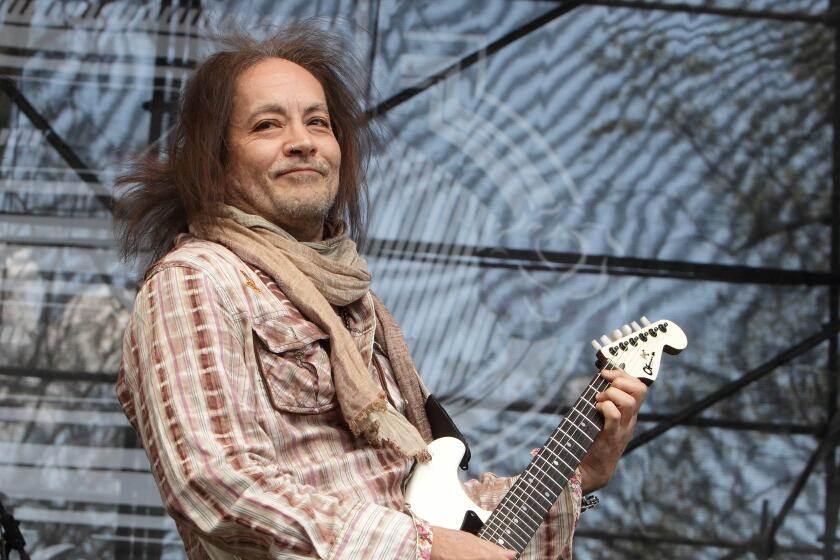

Adds guitarist Kevin Wasserman: “When we were compiling the songs for ‘Smash,’ we thought maybe we should cut out some of these slower things because we don’t want to alienate our hard-core audience. And we just decided, no, isn’t that just selling out in reverse? You know, we like these songs, these songs are fun to play, why don’t we just go ahead and leave them on?”

*

Punk’s players have changed as much as the music has. Sitting around a table at a Mexican restaurant in Hollywood, the four members of Offspring are a million miles from the stereotype of snarling nihilists as they emanate an air of comfortable camaraderie.

Holland, 29, who’s on a leave of absence from his Ph.D studies in microbiology at USC, is tall and talkative, with California beach good looks and long, beaded braids. Friendly and open, he’s clearly the band’s star figure, and by all accounts the one who kick-started the group in its formative days with his drive and determination.

With his thick glasses and long, scraggly hair, Wasserman, 31, fills the role of the nerd intellectual. A single father, he plans to plow some of his Offspring revenue into a university education and become a teacher. Bassist Greg Kriesel, 30, Holland’s partner in the fledgling label Nitro Records, and baby-faced drummer Ron Welty, 23, the father of a 2-year-old son, are the relatively sullen, silent partners on this occasion.

“They’ve got very high ethics,” observes Thom Wilson, who produced all three of their albums. “They’re very honorable people. I don’t think anyone can have all of this attention foisted on them and not be affected by it. But I think that the effect has been minimal. They haven’t turned into big (jerks).”

“When all of this happened,” Holland says, “we’d had the same band members for a long time. We’re a little older, we’re in our late 20s, so we’re maybe a little better equipped to deal with it.”

So why does this wholesome, relatively well-adjusted bunch play songs about police brutality, destructive sexual relationships, isolation, indifference, frustration and disillusionment?

The band’s breakthrough hit “Come Out and Play” is a vignette of gang conflict, punctuated by the ominously spoken line “gotta keep ‘em separated.” Other songs speak from the perspectives of such sociopaths as a freeway gunman and a pyromaniac.

“Yeah, yeah,” Holland enthuses. “That’s colorful. I don’t know. I think I was influenced by the ‘Stealing People’s Mail’ song, you know that Dead Kennedys song? It was mischievous and just kind of dumb and kind of funny. . . . “And people like those songs, they really do. . . . I think they’re very normal feelings that many kids have growing up. That’s really what I’m expressing.”

But Offspring is wary about being depicted as a band with a social/political agenda. The words fun and entertainment keep popping up, and on stage they infuse their scorching intensity with a broad, friendly spirit. They toss in joking versions of Green Day songs, and instead of performing “Come Out and Play” as a sternly cautionary tale, they turn it into a party by bringing fans onstage to try out on the “keep ‘em separated” line.

“We write lyrics that are at least about something,” Holland says, “but we’re not into changing the world or anything like that. We don’t want to be the spokespeople for our generation. . . . The position has been vacated recently, I understand. And I’m not applying.”

Holland means no disrespect by his reference to Kurt Cobain’s grim abdication. He admires Nirvana’s music and he appreciates its role in upending the musical order.

“Punk rock deals with issues that I related to when I was younger, like not fitting in and rebelling, being unsatisfied with the way the world was, complaining about the government and all that stuff.

“That used to be the kind of thing that only a very small minority of kids were into back when I was in high school. And now it seems to be more of a thing that the public in general kind of relates to, I think. Maybe that’s why. It’s relevant to more people.”

Still, success didn’t fall into the Offspring’s laps while the band members sat back and waited for the culture to lock on to their frequency. From its inception, it has been on the attack.

The band sought out its manager, Jim Guerinot, because he had handled bands they admired, including the Vandals and Social Distortion. They tracked down Thom Wilson to oversee their recordings because a decade earlier he had produced the seminal Orange County punk records that inspired them as teens.

Before anyone knew who they were, Offspring hit the road in Holland’s ’78 Toyota pickup, searching for change under the floor mats to pay for gas, sleeping in parks or on pool tables in the clubs they played.

“The thing that I liked was they weren’t gonna wait for someone to do it for ‘em,” says manager Guerinot. “(Holland) was a self-starter. If they needed dates, he booked ‘em. If they needed records sold, he sold ‘em. He was gonna take care of business.”

Holland and Kriesel, high school friends and cross-country teammates at Pacifica High School in Garden Grove, decided to form a punk band in 1984, but they didn’t really get into gear until Wasserman and Welty joined in ’85 and ’87 respectively.

They released their own single, “I’ll Be Waiting,” in 1987, but they couldn’t attract the interest of any of the established punk labels and ended up financing their first album “The Offspring,” which was pressed and distributed by Long Beach’s Nemesis Records in 1989.

They finally caught the ear of Epitaph Records head Brett Gurewitz, until recently the guitarist for the popular and enduring L.A. punk band Bad Religion. Hollywood-based Epitaph released the “Ignition” album in 1992, and the band’s reputation grew in the punk community behind its steady touring and its music’s presence in a slew of surf, skateboard and snowboard videos.

Encouraged by their progress, they were primed when they went in to record “Smash.”

Says Holland: “You could tell as the tracks started going down that there was something kind of neat going on. And like when we got done we thought, ‘Wow, we made a neat little record.’ ”

Though no one in the band had strong feelings about “Come out and Play,” Epitaph pitched the song, with its sneaky, syncopated drum signature, surf-cum-Arabic guitar lead and memorable vocal hook, to L.A. alternative-rock power KROQ. As soon as the station began playing it, listeners responded, and Offspring was off.

“We thought, ‘KROQ and MTV, that’s the end all for getting a song out,’ ” Holland says.

“But then it started going on AOR stations and started going on commercial stations, started showing up on ‘Entertainment Tonight’--they started playing it in between stuff. Rick Dees was playing it in one of his stupid things. We heard about bands playing it at football games. It was this huge summer hit or something. Really amazing.”

What about staying power? For the moment, Offspring has kept doubters at bay by doing well with the follow-up singles “Self-Esteem” and “Gotta Get Away.” They plan to tour solidly through August, then Holland will write the songs for the next album.

It will be the last record due on the original contract with Epitaph. But so far the band has resisted the intensive courtship of the major labels and is in the process of negotiating an extension of the Epitaph deal. A lot of people also assume that the band is bound to go with Guerinot’s new label, which is affiliated with the major BMG--speculation that Guerinot denies.

While the band has managed to remain relatively unaffected by its dizzying circumstances, its sudden prominence has cast a small shadow on the future. Holland realizes that the fun won’t come as easily as it did in the past.

“Sometimes we feel the spotlight,” he says. “It gets kind of uncomfortable, you know, having people watch you all the time. It didn’t matter before if I was the biggest (jerk) in the world. . . .

“On the one hand it’s exciting, and it’s also very scary to think that what we do next time is something that may influence people or be incorporated as part of American culture or something like that. That’s kind of a scary feeling.”

* Times Line: 808-8463. To hear an excerpt from Offspring’s album “Smash,” call TimesLine and press * 5711.

TimesLine is available in the (213), (310), (714), (818) and (909) area codes. From other regions, call TimesLine using the area code nearest you.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.