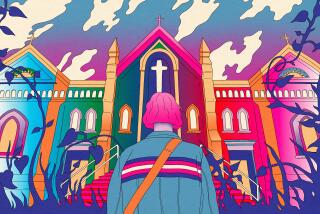

A Profile in Courage : She alone integrated a New Orleans school amid mobs and death threats-- and she prayed for them. Today, Ruby Bridges is a symbol of strength.

NEW LONDON, Conn. — The first time she did this, 35 years ago, Ruby Bridges was surrounded by a mob of screaming people who wanted to kill her.

“You little nigger, we’re going to get you!” they shouted at the 6-year-old girl who had been chosen by a federal judge to integrate a New Orleans public school. “We’re going to poison you until you choke to death!”

Undaunted, Bridges climbed the stairs of William Frantz Elementary School and began the school year, escorted by 75 federal marshals. Her quiet determination marked a turning point in the civil rights movement and, for those who watched closely, it was a stunning lesson in courage and faith.

As the mobs got uglier, Ruby would face them and whisper a few words:

Please, God, try to forgive these people.

Because even if they say those bad things,

They don’t know what they’re doing.

So you could forgive them,

Just like you did those folks a long time ago

When they said terrible things about you.

Television networks beamed footage of the young girl into millions of homes, and President Kennedy pledged federal support for the integration effort. Newspaper editorials told of Ruby from coast to coast, and Norman Rockwell painted a famous portrait of her lonely walk on that first day.

Now, on a sultry August evening in 1995, Ruby Bridges once again climbs the steps to begin a school year. But this time, the 40-year-old mother is being welcomed as a hero--someone who made history and prodded America’s conscience.

In a few hours, Connecticut College would give her an honorary doctorate and thank Bridges for what she did so many years ago. The event also marks an emotional reunion for the New Orleans woman and Dr. Robert Coles, a nationally known Harvard professor and child psychiatrist who befriended Ruby during her ordeal in 1960 and has written extensively about her.

“We want to celebrate the human spirit and I can’t think of any better way than by inviting Ruby Bridges and Dr. Coles to launch our school year,” says Connecticut College President Claire Gaudiani. “Ruby is someone who made a real difference, and the more you learn about her times, the more significant they become.”

As she sits in an auditorium, hours before the speeches begin, the center of all this attention seems shy and more than a little perplexed at the idea that she’s a celebrity. There was a time when Ruby Bridges carried the weight of the world on her 6-year-old shoulders. But that was years ago.

“I’m not a very public person,” she confesses. “And I’m trying not to think about what I’ll be doing in a few hours . . . you know, standing up here and talking to a lot of people. That’s not the kind of thing I normally do.”

Currently, Bridges is a parent-teacher liaison in the same school system she helped integrate. Coles has written a children’s book about her, “The Story of Ruby Bridges,” (Scholastic, 1995), and the royalties will fund the Ruby Bridges Educational Foundation, which spurs parental involvement in schools.

A quiet, thoughtful woman with a sly sense of humor, Bridges has traveled a long path since celebrity first burst upon her. A high school graduate, she had two children as a single mother before turning 20. Two years ago, her younger brother was murdered in a New Orleans housing project, and she fought a bitter, unsuccessful battle for custody of his four young daughters.

Previously a travel agent, she’s married to Malcolm Hall, a building contractor, and has four children. Like many civil rights heroes, Bridges’ life went on after the spotlight faded. Yet the past is never far behind.

“We had a CBS-TV camera crew out to our house in New Orleans several days ago,” Bridges says, fiddling nervously with a paper cup. “At one point the reporter turned to my husband and asked, ‘When did you find out who your wife was?’ My husband looked at me with surprise and said, ‘Who is she?’ ”

*

Ruby Bridges was born in a small cabin near Tylerton, Miss., the oldest of seven children. Her family were sharecroppers, and they moved to New Orleans when her father suddenly lost his job. Two years later, as political pressures mounted to integrate the city’s public schools, her life changed forever.

Sparking a furor, Judge J. Skelly Wright selected four girls from the rosters of all-black schools and ordered them to integrate two all-white elementary schools. Three students went to McDonough No. 19 and Bridges was sent by herself to William Frantz. A spitting, cursing mob awaited her on the steps.

“I’m often asked what I remember from that first day, and mainly it’s that we were riding to school in a car with federal marshals and my mom,” says Bridges. “They were telling us where we’d walk, where we’d go once we got out of the car to get into the school. It was all done for our protection.”

There was no talk from her mother about racism or the need for school integration, she adds, because it would have been tough to explain.

“Think about it.” Bridges says, “What do you say to a 6-year-old? That there’s going to be an angry crowd of people and they don’t want you to go to school because you’re black, simply because of the color of your skin?”

Instead, her mother told her to do what she always did in a moment of fear or confusion--to pray. As weeks passed, Bridges got used to the marshals. She spent two years alone in a classroom with a teacher, because all of the white parents at William Frantz had pulled their children out of the first grade.

Even though crowds continued to scream, she ignored them. The daily prayer Ruby recited seemed simple enough to her, yet it was a revelation for Coles, who happened to be driving by one day when he saw the mob outside her school.

A psychiatrist finishing a tour of duty with the U.S. Air Force, he grew curious about how Ruby was handling the strain. Everything in his clinical background taught him that she would show signs of disintegration, and he set out to chronicle her experience. He also interviewed several members of the mob, carefully documenting the daily abuse they heaped on the girl.

To his amazement, Ruby only got stronger.

“What can you say about a child who prays for those who want to kill her?” he asks, watching Bridges cross the Connecticut campus green. “In its purest form, this was courage and faith. Something many adults never experience.”

A rumpled man with a hoarse, gravelly voice, Coles talks about Ruby to his Harvard students, business executives, theologians, and anyone else who will listen. He becomes almost evangelical in the retelling, firmly believing that he can sway even the most hateful minds with the tale of her courage.

“I wish that [retired Los Angeles police detective] Mark Fuhrman could have seen Ruby go through that mob at the age of 6,” says Coles. “I wish he could see her now. I could only hope he would be given some moral pause.”

Coles’ chance encounter with Bridges in 1960 certainly changed him. Since then, he has devoted himself to the study of children in crisis, focusing on civil rights struggles, migrant labor camps and Third World societies.

He has gone on to win the Pulitzer Prize and numerous accolades for his work--all of which he attributes to the girl from a New Orleans housing project who made a mockery of accepted psychological theories 35 years ago.

“If it wasn’t for Ruby,” he says, “I’d be just another academic watching the clock creep toward 5 p.m. every day. She has utterly transformed me.”

Bridges, in turn, says Coles helped her cope with difficult times, and calls him a father figure, having lost her own dad in 1978. Both private people, Bridges and Coles shyly confess that they love each other very much.

*

The story moves adults, and now children can learn from it as well. This summer, Connecticut College, Scholastic Inc. and the New London public schools sponsored a program during which students read Coles’ biography of Bridges. Afterward, they wrote essays about courage and the book’s message.

Beautifully written and illustrated, “The Story of Ruby Bridges” is no ordinary children’s tale. It tries to explain racism without frightening youngsters. Several hours before the day’s ceremonies begin, Bridges and Cole gather on a patch of campus lawn with 18 young essayists, and listen to them read aloud:

“One time me and my friends were going to steal something from the store,” says Courtney Glenn, 10. “I told them no. They said if you don’t steal anything, we are not friends anymore. So I said, ‘Forget you,’ and left. . . . To be brave you must listen to your conscience and do what’s right.”

The gathering holds its collective breath when Qiana Holland, 11, recalls the time her drunken father exploded with rage and began beating her mother:

“I was stopping my father from hitting Mom. When it was over, I was glad. It took me a lot of courage to be away from my father and to be split up.”

Bridges gives Qiana a hug and tells the group there are times when people pay a price for courage. Although school integration was eventually accepted, she says, her father lost his job as a gas station attendant because of pressure from irate white customers. The tension and humiliation ultimately led him to divorce Ruby’s mother, who had to raise seven children by herself.

Recognizing their plight, neighbors and others pitched in to help. Ruby became a cause celebre, and her family got generous donations of food, clothes and money. Yet she never let the notoriety turn her head, she says.

“We’d get these boxes of clothing in the mail, and my mom would say, ‘What makes you think all this is for you? You’ve got a sister right behind you.’ So then I realized, we’re all in this together. We have to help each other.”

It’s a lesson Bridges hopes to share with others, especially in the African American community. She urges parents to play more of a role in their children’s public school education. She wants black people to take better care of each other, on issues such as drug abuse, teen pregnancy and juvenile crime.

Her brother’s death galvanized her to become more involved in schools, she says, and Coles’ offer to help the Ruby Bridges Foundation launched her on a new career. The world has come full circle for the 6-year-old who climbed the school stairs that ugly day in New Orleans. Now, after hours of nervous waiting, the moment has arrived in Connecticut when she would do it once again.

As Bridges walks down the auditorium aisle, 1,600 students are on their feet, cheering her on. Many have tears in their eyes, and Coles is overcome with emotion. Above the din, President Gaudiani fights to be heard:

“Please join with me in welcoming Ruby Bridges--the right way.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.