Mother’s Helper

- Share via

The room, not much larger than a storage closet, was cluttered with outdated surgical equipment, most of it better suited to a museum than the Women’s Hospital at County-USC Medical Center.

Most people walked by, oblivious. But Dr. Richard Marrs, a young obstetrician-gynecologist fresh from Texas to pursue a fellowship in reproductive endocrinology, eyed the tiny quarters with great interest.

He had recently obtained approval to launch an in-vitro fertilization program and had already assembled some basic equipment.

What he needed was space for a laboratory.

This broom closet might be just the digs.

He broached the topic with the operating room supervisor, who needed some persuading. Where would the stored equipment be put?

Quickly, Marrs found a final resting place: the hospital roof, where other abandoned pieces of equipment were already soaking up the smog and sun of East L.A.

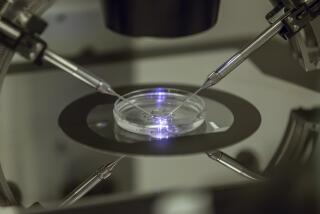

After a long weekend of scrubbing and disinfecting, the IVF team set up shop. Then things happened quickly. Marrs can still recall one of his first attempts to join egg and sperm outside the body: “I couldn’t sleep that night.” In the morning, he hurried back to the lab. “The egg was fertilized. And I thought, ‘This is unbelievable. We can do this.’ ”

The fifth patient treated got pregnant and gave birth in June 1982 to the program’s first IVF baby--the first one born west of the Mississippi.

*

Since that success, Marrs has remained on the fast track. While he is not a household name, he is definitely a VIP in fertility circles. Four years after the USC program’s first successful IVF pregnancy, Marrs helped produce the country’s first frozen embryo pregnancy. Over the years, he has published more than 100 articles in medical journals and textbooks and helped to draw up a code of ethics for a fledgling specialty.

When he presented data at scientific meetings in the early days, the room fell silent, say people who were there. “Marrs would go to meetings, and he’d be like the Pied Piper,” recalls Dr. Daniel R. Mishell Jr., USC professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology, who gave Marrs approval for the IVF program back in 1981.

Now 49 and silver-haired, Marrs is medical director of the Center for Assisted Reproductive Medicine at Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center after stints at two other L.A. hospital fertility programs. He also heads California Fertility Associates, where he practices with three other physicians.

Just published is his new book, “Dr. Richard Marrs’ Fertility Book” (Delacorte), co-written with a former patient (now the mother of twins) and her television-writing partner. Next month, the West Coast’s first “test tube” baby turns 15, and Marrs is busy organizing an international scientific conference in Hawaii for later this year, where presenters will glance back and look ahead.

The saga of the broom-closet-turned-lab not only reflects Marrs’ tenaciousness but demonstrates just how quickly the IVF technology has evolved, thanks to the efforts of Marrs and others. Back in 1981, IVF centers were often the target of protesters, some of whom contended the technique was “going against nature.” Within the span of a decade and a half, the burning question has evolved from “Should IVF be used to help a woman conceive?” to “How old is too old?”

But there’s no reason nor time, Marrs contends, for laurel-resting. He lobbies for better insurance coverage for infertility treatments, tries new approaches to achieve pregnancy and denounces the money-back guarantees offered by some of his competitors. In a cutthroat field that has been subject lately to investigations for fraud and theft of eggs and embryos, Marrs is a fertility doctor above reproach, even his most jealous competitors acknowledge. And even with three other physicians in his Santa Monica private practice, he still works, by all accounts, like a young gynecologist on a fellowship with something to prove and a demanding department head to please.

One co-worker estimates that Marrs works 14 hours a day, seven days a week.

Pure hyperbole, Marrs at first insists during an interview in his office across the street from the Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center.

“I do work seven days a week,” he says, “but that’s because for 15 years I’ve tried to figure out how to make women ovulate Monday through Friday, and that’s been one of my biggest failures. If I’m going to do this work, I need to be here when the patient’s ovulating.”

In practice with Marrs are his wife, Dr. Joyce Vargyas (from whom he is separated but on friendly terms), Dr. Andrea Stein and Dr. Guy Ringler. Vargyas was a senior resident at USC when she met Marrs; they married soon after and spent the next decade together working and researching. When they separated five years ago, they decided the split should not extend to their practice nor to the parenting of their two children, Ashley, 15, and Austen, 9 (both conceived without IVF).

“We’ve worked together so long, it’s easy for me to take care of his patients and vice versa,” explains Vargyas, who sees their skills as complementary. “I tend to be more verbal; he is technically very good. I’m good at cutting to the chase; he’s good at keeping patients calm and giving them hope.”

Even with four doctors in the practice, Marrs is considered by many patients as the “name” doctor, the one to see.

Stories abound from other fertility doctors about Marrs’ ego, but he’s described quite differently by some of his staff. “Reserved” is the first word used by Carmen Rodriguez, who has worked in Marrs’ office for seven years, handling administrative and other tasks.

Other workers describe him as ethical and level-headed. Jody Greene, an embryologist who helped Marrs clean the broom closet and has worked for him ever since, calls him “intense” and “a hard worker” who has high expectations. (His diet, she points out with a laugh, could improve. Diet Coke is a staple, and she remembers his offer to share his Twinkies during one especially hectic day.)

In the operating room, Marrs is completely at ease. On a recent morning at the hospital, he greets his first patient, a donor who has come in for ultrasound retrieval of the eggs. “We’ve got some great music for you,” he says with a grin. The greeting draws smiles from his staff, who say the OR boombox is turned permanently to Marrs’ favorite country and western station. (And, should anyone be foolish enough to switch stations, says nurse Barbara Perini, a notch marks the preferred spot on the dial.)

By now, Marrs has inserted the probe and is looking at the ultrasound screen. With a practiced eye, he predicts the yield: “She’s going to have at least 20.” She has 22.

Retrieving eggs--each tiny one carrying the potential for a life--is still heady stuff for Marrs.

But later that morning, during office visits, he has to deal with the other end of the spectrum: the long-term patient who has not maintained a viable pregnancy. This day, however, he has some promising news for the 40-year-old Los Angeles homemaker who has been his patient for 13 years--and is still childless.

“Well,” Marrs says, examining the ultrasound screen, “you have ovulated.” Next comes retrieval, insemination and a large dose of hope.

At some point, Marrs says later, this woman probably should give up. And he’s told her that. But it’s a tough decision for them both. “I feel inadequate every time she walks in the door,” Marrs says. One of the hardest lessons of his career, he says, is “realizing you can’t produce a baby for everybody. You have to face those failures.” Complicating this case is the inability of the woman’s husband to consider egg donation or adoption as alternatives.

*

Under the best of circumstances, IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies are not easy on patients--physically, psychologically or financially. So Marrs tells patients, straight out, the chances for success.

“If the woman is under age 34, she has about a 40-plus percent chance of being pregnant each time she has embryos. So she may take one or two cycles, or three at most. If the woman is 41, she may never get pregnant, or it may take her five or six cycles with her eggs. If she’s using an egg donor, it’s a 50% outcome per cycle, so it may take one or two cycles.”

His personal comfort level, age-wise, stops at 50 to 55, he says, even in the wake of a 63-year-old’s recent delivery after obtaining eggs from a donor. But each case is evaluated individually.

Fees are also discussed upfront.

“Last year, we were able to reduce our IVF cost by about 22%,” he says, partly the result of contract renegotiation with the hospital. On average, it’s $6,500 per IVF cycle. “That same cycle in New York City will cost you about $12,000,” says Marrs, but partly because insurance coverage tends to be better there.

For years, he has crusaded to persuade insurance companies to treat infertility as the disease it is, not elective surgery. “No matter what causes it,” he says, “there is a disease associated with it.”

When health care reform talks were underway during President Clinton’s first term, Marrs helped organize Advocates for Infertility, a physicians’ group, and flew back and forth to Washington to persuade officials to include coverage.

“Since then, more and more companies have started to add infertility coverage,” Marrs says. About 20% of his patients have coverage.

It’s difficult to determine what irks him more--the insurance situation or the money-back guarantees offered by some of his competitors if pregnancy is not achieved.

“I may as well be selling used cars,” he says of the arrangement. In theory, a money-back guarantee could work, he says, but complains that his competitors “front-load” the package so they’ll make a healthy profit either way.

*

It is the kind of attitude one would expect from someone born in tiny Paducah, Texas, the middle of three children. Later, his family moved to Kerrville, where Marrs went to high school and community college before transferring to the University of Texas, Austin, for his bachelor’s degree and medical school.

He played high school basketball and can still find his way up and down a court. Recently, he suited up for a benefit basketball game between the Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center and the Santa Monica Police Department, only a little bothered at game’s end that he was the oldest guy on the court and that the opponents were more buff and better shooters.

He was raised Catholic but has trouble with the church’s “rigidity” and does not attend Mass regularly.

Marrs and Vargyas try to maintain a flexible schedule that allows Ashley, a high school freshman, and Austen, a third-grader, to go back and forth between Vargyas’ place in Brentwood and Marrs’ home in Pacific Palisades.

“Ashley will call and say, ‘Dad, can I come over tonight?’ and I’ll say, ‘Sure, Ashley, what’s going on?’ ‘Nothing, I just want to be with you.’ Then she’ll get over here and say, ‘Dad, I’ve got this paper due. . . .’ ”

Marrs coached Austen’s basketball team this year and remains his son’s favorite barber. But when Austen asked for something a little different than Marrs’ standard buzz cut, Dad had to confess his haircut repertoire has a single entry.

Hair is also a frequent topic of discussion these days between father and daughter. Before Valentine’s Day, Ashley streaked a bit of her long brown hair a rich red and assured her freaked-out dad it was only temporary. Marrs waits--and frets--and can’t help asking, “Ashley, when’s it going to wash out?”

Once a month, Marrs tries to travel to Springville, Calif., to work on the ranch bought three years ago with two partners, always asking Ashley and Austen along. But often, the trips get canceled because a patient needs him in L.A.

It was one of his patients, Lisa Friedman Bloch, who first brought up the idea of a book. An agent obtained a “healthy six figure” advance for Marrs, Bloch and her writing partner, Kathy Kirtland Silverman.

For two years, the trio collaborated, with Marrs often providing burritos grandes to keep up everyone’s energy. Marrs typically wrote from 10 p.m. until 1 a.m. “When I’ve got something to do, I get five hours of sleep . . . and it doesn’t bother me.”

A book signing party at 72 Market Street in Venice in late March drew many former patients--and their offspring.

*

Most former patients with children clearly adore him, but even his fans don’t think he’s perfect. One patient praises his bedside manner but complains that Marrs is “hard to get ahold of.” When she calls the office with questions, it is often the nurses, not Marrs, who respond to her calls, she says.

As he’s changed hospital affiliations, he knows he has left some ill will in his wake. From USC, he went to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, but left after a year because a contract provision about research funds, he says, wasn’t met. Next, he set up shop at Good Samaritan Hospital, then moved to the Westside seven years ago.

But even people with whom Marrs has not always seen eye to eye praise his work.

“He’s got a great personality,” says USC’s Mishell. “He was a hard worker then, and I think he still is.”

Among those thanked on the acknowledgment page of Marrs’ book is Dr. Charles March, a USC professor of obstetrics and gynecology and a Glendale fertility expert. Over the years, he says, Marrs has provided a good image for the specialty.

“When you’ve got picketing [in the early days], real or imagined abuses, followed by cloning and a new wave of reproductive ethicists being spawned, you need a high-profile, untainted person to go to government meetings and to keep some of this in perspective.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Dr. Richard Marrs

Claim to fame: Pioneer in in-vitro fertilization and other assisted reproductive technologies. Produced one of the world’s first “test tube” babies; helped create the first pregnancy in the U.S. from a frozen embryo.

Back story: Born 49 years ago in Paducah, Texas; moved to Southern California in 1977 to pursue a fellowship in reproductive technology at USC. Now lives in Pacific Palisades.

Family: Separated, but shares parenting with Dr. Joyce Vargyas of their two children, Ashley, 15, and Austen, 9.

Passions: Listening to country-western music, visiting his ranch, crusading for IVF issues, coaching his son’s basketball team, persuading his daughter not to color her hair.

On his view that age 55 is generally a good maternal age limit for assisted reproduction: “I do not believe that women or men are good parents of a toddler when they are toddling around at age 60 or 65.”

On what he sees as inadequate health care coverage for IVF patients: “The powers that be decided that having a child is elective. Ask them how they would feel if they didn’t have their children.”

On the frustration when IVF techniques are not successful: “These women are 43, 44. They look 34. They’re healthy, they’re active, they exercise. Why can’t their eggs work for them? They feel young.”

On treading the fine line between fertility specialist and counselor: “I tell the patients, ‘I will never tell you what to do. I will only tell you what the statistics are, what our success is, what my experience is and what my feelings are. But you have to make the decision of how and what you are going to do.’ ”