Waits, Crowding Worsen Tensions in INS Centers

EL CENTRO — A new law designed to deport immigrants convicted of crimes is creating a volatile climate at federal detention centers by filling them with an increasingly hardened and desperate population, including many longtime legal U.S. residents who are fighting to stay, but have little chance of success.

Although immigration officials boast of removing 1,000 criminals a week by aggressively enforcing 1996 federal reform laws, some are fretting about how to house the thousands of people who pass through the system each month, and how to maintain order and calm in the crowded detention centers.

Twice in the past two months, detainees, many of whom have little connection to their home countries, have rioted at the Immigration and Naturalization Service detention center in El Centro, where nearly all of the 620 men being held for deportation have felony records. In the most recent incident Monday, three guards were beaten before the 180 detainees surrendered.

“We’ve in effect made our facilities like prisons, but they’re not designed like prisons,” said Kim Porter, deputy assistant director for detentions and deportations for the INS in San Diego.

The new laws, part of an immigration reform package passed by Congress in 1996, greatly expanded the list of crimes for which noncitizens can lose their legal residency status and be deported. The list, which had previously been limited to murder, rape and other major felonies, now includes such crimes as selling marijuana, domestic violence, some cases of drunk driving, and any conviction carrying a sentence of a year or longer.

Effects of Law Become Evident

The law applies retroactively. Some legal residents who finished their sentences 20 years ago have suddenly found themselves being detained and deported.

Immigration judges, who are employed by the U.S. Department of Justice, are allowed almost no discretion in such cases. And most of those detained for deportation hearings are not permitted to post bond.

“It treats shoplifters and murderers the same, and that doesn’t fit anybody’s idea of justice or common sense,” said former Rep. Bruce Morrison, a Democrat from Connecticut who chaired the House immigration subcommittee in the late 1980s and who served on the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform until it disbanded in December.

Morrison called the detentions and deportations “a disaster” that will lead to further overcrowding and uprisings. “We are seeing, and we’re going to see increasingly, the folly of misdefining the problem and overreacting,” he said.

Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), who now chairs the House immigration subcommittee and was a sponsor of the immigration law, counters that crowding and security problems could be resolved by acquiring more detention space.

Smith said the majority of those detained and deported are serious felons who would be likely to commit more crimes if allowed to remain in the United States. “[Deporting criminals] is one of the most popular parts of the law,” he said. “The American people like a law that keeps criminals out of their communities.”

Criminal deportations have soared under the new law. The INS removed about 51,000 ex-convicts in the last fiscal year--nearly double the number of five years ago--and the pace has held steady this year, said INS spokesman Russ Bergeron.

Finding space for all those criminals while their deportation reviews and appeals work through the system has been “challenging,” Bergeron conceded, even though the INS has been adding thousands of beds a year by leasing space from prisons and jails around the country.

The INS is now able to house about 13,000 criminals at any time, with about 3,400 in the agency’s nine detention centers and the rest in leased prison and jail space, Bergeron said.

The patchwork of detention space and high turnover rate--about 60 days on average for criminal illegal immigrants--means a daily juggling act by INS detention and deportation officers such as Kim Porter in San Diego.

On any given day, Porter watches over an average of 1,000 detainees, about 80% of whom are criminals. They take up El Centro’s 650 beds and leased space in jails and honor camps around Southern California, including the Santa Ana jail. Occasionally, motel rooms are used to house low-risk female detainees.

Officials Search for More Space

Almost every morning, Porter said, he calls a long list of prisons and jails, searching for beds. “I just sent 50 up to Seattle on Monday,” he said recently.

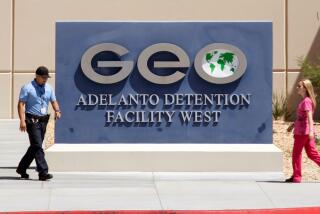

Two INS detention centers are in California--the El Centro facility and a 500-bed center at San Pedro. The Los Angeles district also leases 500 beds for criminal immigrants at the county jail in Lancaster, said INS deputy assistant director Leonard Kovensky.

A pending federal lawsuit alleges inadequate access to medical attention, legal assistance and other shortcomings at all INS lockups in the agency’s Los Angeles district, including the facilities in San Pedro, Lancaster, the basement of the Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles and a converted motel near Los Angeles International Airport. Settlement negotiations are continuing in the class-action case, said Niels Frenzen, an attorney with the Public Counsel Law Center in Los Angeles who represents INS prisoners.

San Pedro has not experienced the same degree of problems as El Centro, but it is better suited for a criminal population and holds fewer criminals, Kovensky said.

Although nearly all detainees in El Centro have criminal records, only about 60% of those in San Pedro do. The rest are immigrants without visas who are seeking asylum, claiming they would be endangered if returned to their home countries.

Even so, Kovensky said the climate at the San Pedro center is vastly different than it was five years ago, when the population was dominated by illegal immigrants picked up at the airport or job sites, along with the asylum seekers. “Obviously we’re more alert, more concerned,” he said. “You have to be aware, and look for signs of depression among other things.”

Hector Najera, director of the El Centro center, said that when he began working there 20 years ago, most detainees were migrant farm workers whose only offense was crossing the border illegally. Generally, they were released back to Mexico within 24 hours.

Now, many come with long criminal histories and fears. Dressed in color-coded jumpsuits--with red signifying the most dangerous--detainees are carefully segregated to avoid clashes between rival cliques. Most were convicted on drug charges, Najera said, but others include suspected murderers and child molesters.

Several years ago, the chain-link fence surrounding the set of squat brown buildings just north of this border agricultural city was nearly doubled to 10 feet and topped with thick rolls of concertina wire. Construction workers will soon add the center’s first visitation rooms.

Although some detainees are deported within three days of arriving, many with appeals pending have been at the El Centro facility for a year or longer, Najera said.

Those from Cuba, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia have become “virtual lifers,” he said, because their home countries have limited or no diplomatic relations with the United States. They can’t be deported, but under the new law, they can’t be released.

“These people are on edge, and they know they have no hope,” Najera said.

In late January, about 50 such “lifers” barricaded themselves in a dorm room and set fire to blankets and mattresses before guards were able to restrain them. Those detainees were dispersed to jails throughout the West.

Again on Monday night, detainees--including Mexican, Central American and European nationals--took over a dorm, this time wounding three guards before they were persuaded to surrender Tuesday morning.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is looking into the uprising, and ringleaders will be prosecuted, said Porter, the detention official. “But sooner or later, we’ll get them back,” he said.

For those held at the center, life is a monotonous grind broken up by three meals a day in the large open cafeteria and occasional recreation time in the bare dirt yard. Most of the day, detainees are confined to stuffy, dank dorm rooms, where cots are arranged in tight rows about 20 across.

Louis Nine, whose godfather, Leonardo Lazo, has been in the center since late December, said Lazo has complained of frequent lock-downs and said “frustration is running very high.”

Lazo, 42, emigrated from Cuba with his family when he was 10 years old, Nine said. A carpenter, he was arrested in October when he tried to bring 56 pounds of marijuana across the Mexican border.

Under a plea bargain agreement, Lazo was convicted of a misdemeanor and served 28 days, Nine said. After finishing his sentence, he was immediately transferred to El Centro and held for deportation. Now he is among the virtual lifers.

A number of immigration attorneys also take issue with the new law, but said they can offer little hope for people affected by it.

“Every day I’m contacted by people in this situation, and 95% of the cases I cannot take,” said San Diego lawyer Lilia Velazquez. “If they’re convicted aggravated felons, they’re not eligible for a waiver. My only role would be to hold their hand when they stand before the judge. With or without me, they’re going to be deported.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

More Being Sent Home

New laws meant to remove criminal immigrants from the United States have produced a dramaticrise in the number of deportations of criminals.

Source: Immigration and Naturalization Service

*

Times staff writer Patrick J. McDonnell contributed to this report.

*

* THE HUMAN TOLL: Deported loved ones leave behind shattered families. B1

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.