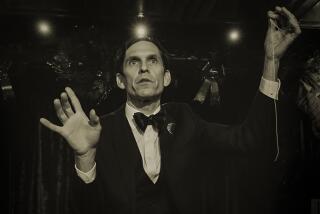

Magician Doug Henning Dies of Liver Cancer at 52

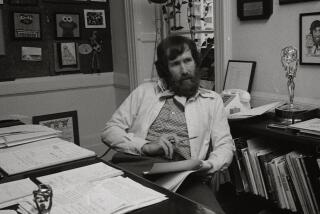

Magic plus theater equals art, the 20-year-old psychology major argued, convincing the government in his native Canada to give him a $4,000 study grant with the goal of reviving magic as a theatrical art.

The diminutive Doug Henning soon landed at Hollywood’s Magic Castle, grant in pocket, for a three-month cram course. He was determined to learn enough from the veterans to put magic in a play.

The result was “The Magic Show,” which lured mesmerized audiences to Broadway for 4 1/2 years and earned the young illusionist the first in a string of annual NBC television specials. Lloyd’s of London would soon insure his hands for $3 million, or $300,000 per finger.

Canada’s investment in the arts paid off. Henning had revived magic in a big way.

“When Doug opened that show on Broadway, that was the starting point of a huge boom in magic that has continued to this day,” Las Vegas magician Lance Burton said Tuesday. “Every magician that’s out there working today owes Doug Henning a great debt.”

Henning, the man who performed Harry Houdini’s legendary water torture escape on national television before a live audience and later became a spokesman for the spiritual leader Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, died of liver cancer Monday in Los Angeles. He was 52. He is survived by his wife of nearly 20 years, Debby.

Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Henning became intrigued by magic as a child when he saw a magician levitate a woman on television’s “Ed Sullivan Show.” His mother bought him a magic kit. But the boy was more interested in sports and then began premed studies and earned a psychology degree at Canada’s McMaster University. Shut out of basketball by his size, Henning revived his interest in magic.

He was credited with updating an old-fashioned vaudevillian entertainment by modernizing its image with his long hair, tie-dyed T-shirts and jeans instead of the magician’s traditional top hat and tails. He added stage sets and dancers and speeded up the illusions. (Houdini traded places with a prisoner in a trunk in 20 seconds; Henning did it in one-third of a second.)

Henning’s television shows won him an Emmy and seven Emmy nominations. He crisscrossed the country with his show and returned to Broadway in the 1980s with “Merlin,” which was nominated for five Tony awards, and “Doug Henning’s World of Magic.”

He also created special effects for tours by his friend, Michael Jackson.

Wonder, Henning always said, is necessary in life, and magic can reawaken the wonder that occurs naturally in children but is lost to cynicism as people grow up. Henning’s own sense of wonder fueled his professional success and personal appeal.

“It’s important to me to create the largest wonder,” Henning told The Times in 1984 before appearing at the Los Angeles Music Center’s Ahmanson Theater. “If I produce a 450-pound Bengal tiger, it’s going to create a lot more wonder than if I produce a rabbit.”

So he traveled with two tractor-trailer loads of 15 sets, equipment for 30 illusions and a menagerie. In that Ahmanson show, for example, he turned a woman into a black panther, sawed two women in half and reassembled them on each other’s legs, walked through a mirror, suspended his wife in midair before making her vanish and reappear in a box hanging over the stage, escaped from a chained trunk like Houdini and conjured up the Bengal tiger.

“The reason I can give wonder,” Henning told The Times in 1980, “is that I feel wonder about the world: the stars, a tree, my body--everything.”

At the height of his popularity in 1987, Henning dropped out. He abandoned his “illusion magic” for what he saw as “real magic”--the transcendental meditation and levitation ability of his friend and guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, with whom he began to study in the early 1970s.

“Magic is something that happens that appears to be impossible,” he said in an interview with The Times. “What I call illusion magic uses laws of science and nature that are already known. Real magic uses laws that haven’t yet been discovered.”

Henning went to India for a time to work with the maharishi, telling The Times by telephone in 1988: “It was the fulfillment of my career to do this. I’ve spent my time learning new card tricks and entertaining all the kids in the mountains. The people are so pure. They haven’t been touched by cynicism.” He also tried to help the maharishi develop a series of theme parks to be known as Vedaland with pavilions devoted to enlightenment and transcendental meditation--first in India, then in Orlando, Fla., then in Niagara Falls, Canada. The Canadian version even promised a building that would levitate.

Henning performed occasionally in the mid-1980s to raise funds for the maharishi, but also sold many of his illusions to magician David Copperfield.

In further support of the maharishi, Henning also ran (unsuccessfully) for political office in England and Canada as a member of the maharishi’s Natural Law Party. At one point derided as “crazy” and a has-been, Henning insisted to one Canadian political reporter in 1994: “I’m a visionary.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.