Job-Rich, Housing-Poor

The steady succession of announcements that the prices of homes in Orange County are marching ever upward may be splendid news for homeowners, but it also signals that the affordable-housing problem is getting even worse.

More than 60,000 new jobs were created in Orange County last year, an impressive number that testifies to the vitality of the county. There has been a roaring comeback from the economic downturn of the early 1990s and the bankruptcy of county government five years ago.

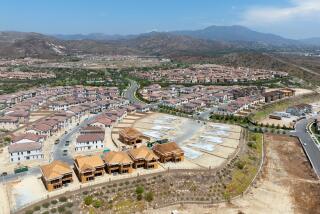

But only 10,000 new housing units went up in the county last year. That’s one for every six jobs created, a poor record that may be sowing the seeds of economic problems. People who come here for jobs can’t afford places to live, raising the specter that new companies won’t move into the county if their employees can’t find living quarters.

Affordable housing is not a new problem for the county. But too few cities have bothered trying to do much. State law does require affordable housing, but enforcement generally comes only when municipalities seek funds under the Community Redevelopment Act. When the cities take the money, they are required to use 20% of the increased taxes in the redevelopment zone for affordable housing. That does not add up to enough units to be meaningful.

The demand for rental housing for those with low incomes is so great that when an apartment becomes vacant, typically four people apply for it. One Huntington Beach man who recently advertised to rent two of the four bedrooms in his house received 120 responses, including some offering to pay more than the $650 rent he was seeking.

Many of the new jobs created in the county in recent years were in the service industry, minimum-wage occupations such as janitor, hamburger flipper, dishwasher. A recent study by two groups specializing in providing low-income housing found that a couple working two minimum-wage jobs would each have to work 11 hours a day, seven days a week, to rent the average apartment in Orange County, which costs more than $1,000 per month.

Thus it is no surprise to find some tenants in Santa Ana, Anaheim and other of the county’s older cities renting out parts of apartments, sections of rooms and garages. Santa Ana officials say eight to 10 people sometimes live in a one-bedroom apartment in order to come up with the rent. But that puts an intolerable strain on a building and on city services like sewers, which have to serve more people than designed for, and police, who have to respond more often to quarrels among people whose tempers get worse as the apartments become more crowded.

Studies also indicate it can take two minutes longer to vacate a burning apartment if it is overcrowded, because of the extra furniture and people. Those minutes can be the difference between life and death.

The picture is not much brighter for many Orange County residents who want to own their homes and stop renting.

In October, half the houses sold in Orange County went for more than $244,000. That can be out of the reach of teachers, firefighters, secretaries and other middle-class wage earners. Homeowners may not want lower-priced housing built in their neighborhoods for fear they will lower property prices. But city officials worry that companies may move out of the county or at least look elsewhere to expand operations if they know their workers cannot afford to live nearby.

The Affordable Home Ownership Alliance in Orange County plans to raise $50 million to provide low-interest loans to developers who will build housing for those earning low or moderate wages.

That’s a commendable goal. But cities have to do their part, as well, and approve housing that those in the middle sector of society can afford to buy. Some groups that want to build rental housing in the county say they have funds, but not enough to buy in a county where land is so expensive, especially if their applications to build multiunit rental housing are turned down by planning commissions.

Cities have a “housing element” as part of their general plans. As they update them in the months ahead, they have to realize it is in their own self-interest to approve plans for more affordable housing. When companies leave town, they take jobs and taxes with them. That’s of no benefit to anyone except the new, favored destination of the company and its employees.