Let’s Give a Toast to Prohibition, Circa 2000

The excesses of copyright law were never better illustrated than by U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel’s ruling last week on Napster, the music-swapping Internet service. Never mind that the service had attracted 20 million users. In fact, Napster’s loyal following contributed to its downfall.

In her ruling, which was stayed on Friday, Patel cited the Recording Industry Assn. of America’s claim that if she didn’t issue an injunction immediately, Napster would have as many as 70 million users by year’s end, all pirating copyrighted music.

The Napster case is only the latest example of a troubling trend: The hijacking of copyright law by vested interests to the detriment of the general public. The U.S. Constitution authorized Congress to “promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

Congress adopted the first Copyright Act in 1790, establishing a 14-year copyright term. In a political compromise, renewals for another 14 years were authorized. By 1909, the term doubled to 28 years, renewable for a second 28 years. In 1976, the term grew again: This time, to the author’s life plus 50 years and to 75 years for “works made for hire.”

In 1998, in the same package of bills as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (the “DMCA” on which Patel based her injunction against Napster), Congress added another 20 years to copyright terms.

Now many copyrights last for 95 years. On unpublished works, the term is even longer--up to 120 years. That’s a “limited time”?

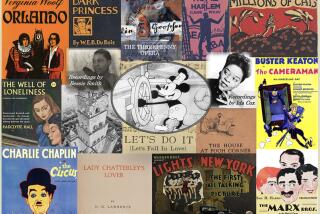

Meanwhile, the public domain--the body of works available for everyone to use or expand upon--has continued to shrink. And the Fair Use Doctrine, which allows many uses of copyrighted works, has been all but ignored in recent congressional enactments. At the same time, the explosive growth of new digital technologies has made copyright law more and more irrelevant.

When powerful vested interests like the recording industry win ever greater copyright protection at the expense of the public domain, it’s easy to see why 70 million computer users would simply ignore the copyright laws and share music--music that is otherwise unavailable online for the most part. For that matter, the thriving creativity on the Internet, flourishing in a culture dominated by principles of free sharing, calls into question the basic constitutional rationale for having copyright laws. Do these laws really “promote the progress of science and useful arts,” or do they sometimes hinder progress? Did copyright laws motivate the thousands of computer enthusiasts who shared in developing the open-source Linux operating system? Did these laws motivate the young people who have written so much freeware in recent years?

In reality, copyright law and related legal concepts have been misused more than once to hamper “progress of science and useful arts.” The attempt by Hollywood interests to curb or slap hefty royalties on VCRs is one example (that effort was halted by a U.S. Supreme Court decision only after a federal appellate court upheld such a royalty system). History offers other notable examples, among them, an attempt by newspaper publishers to stifle radio news in the 1930s, and the software industry’s attempts to abrogate the First Sale Doctrine, which allows the purchaser of a copyrighted work to resell it or donate it to a library without paying additional royalties.

In fact, if libraries were a recent invention, wouldn’t they be a prime target of copyright infringement lawsuits? Don’t they enable millions of people to share copyrighted materials instead of purchasing their own individual copies?

Whatever the outcome of the recording industry’s litigation against Napster, there can be little question that it is a futile rear-guard action. It cannot halt music sharing. The arrival of the Internet and the digital revolution will force us to reexamine basic copyright precepts or watch intellectual property law become as irrelevant and unworkable as Prohibition.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.