8 Diabetics Freed From Insulin Shots

Canadian researchers have successfully freed eight diabetics from insulin dependence by using a new combination of anti-rejection drugs to transplant insulin-secreting islet cells.

All of the subjects have remained insulin-free for four to 15 months, a remarkable rate, because fewer than one in 10 patients who received islet transplants previously were able to escape their daily shots.

“This is perhaps the most important finding in Type 1 diabetes research in the past decade,” said Dr. Richard Furlanetto, medical director of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. “It represents a real proof of concept.”

The report is scheduled to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine in July, but the journal posted the paper on its Internet site Tuesday because of its public health significance.

The tight control of blood sugar levels offered by islet-cell transplants gives long-term hope to the estimated 1 million Americans with Type 1 diabetes because it sharply reduces the risk of long-term complications, such as nerve and kidney damage and blindness, noted Lisa Kory, executive director of Transplant Recipients International Organization.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the patient’s own islet cells die for reasons that are not clear. The patients can then be kept alive only by giving them insulin injections.

Now that the Canadian team has shown that islet transplants will work, “the Gold Rush is on” for other groups to replicate their work and improve on it,” said Dr. David Harlan of the National Institutes of Health’s Organ Tissue Transplant Research Center.

The NIH and the Juvenile Diabetes foundation are gearing up for a larger trial of the technique this summer at eight institutions that have previously demonstrated the ability to isolate islet cells. Other groups are expected to attempt it as well.

Even if the new trials are successful, the technique still faces obstacles that could limit its use. One is that recipients must take immune-suppressing drugs for the rest of their lives, which places them at risk of infections and certain types of cancer.

Perhaps more important, treatment of each patient requires islets from two pancreas donors. Only about 30,000 donor pancreases are available each year, and that scarcity could cause a severe bottleneck, limiting widespread use of the transplants.

Researchers are attempting to grow islet cells in culture and to produce them from primitive embryonic cells called stem cells, but success with either approach is likely to be many years off, noted Dr. Robert Sherwin of Yale University, president-elect of the American Diabetes Assn.

Nonetheless, “this is going to be a tremendous advance for people with Type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. James Shapiro of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, the lead author of the study.

It has certainly proved to be one for Mary Anna Kralj-Pokerznik, a junior high school teacher who was one of the eight volunteers treated at Edmonton. “I can now do things I never dreamed I would do, like teaching an entire morning or afternoon without stopping to eat or testing my blood glucose, [or] going for walks when I want,” she said.

Surgeons have been investigating transplants to cure diabetes for at least 30 years, but success rates have been low. Their first attempts were directed at transplanting the entire pancreas, but that requires a major operation and the organ is easily rejected, which means massive amounts of drugs are required to suppress the immune system.

Physicians have generally believed that the risks from diabetes are smaller than the risks associated with that immunosuppression. Pancreas transplants are now generally attempted only when the patient is already immunosuppressed after receiving a kidney or liver transplant. About 1,200 pancreas transplants per year are performed worldwide.

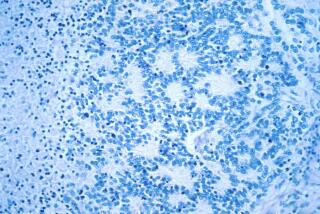

Because insulin-secreting islets account for only about 3% of the mass of the pancreas, it is generally believed that they are less likely to be rejected. Several hundred islet transplants have been performed around the world, but only about 8% of the transplants have survived for as long as a year.

“What James Shapiro and his colleagues have shown is that you can consistently [get long-term survival],” Furlanetto said. “They’ve moved it into the realm of scientific practice.”

The group was successful for two reasons, he said. One is that it is “the best in the world” at isolating islets and thus was able to infuse large enough numbers to achieve control of insulin levels.

The second and more important reason is that researchers used a new regimen of immunosuppressive drugs. In the past, surgeons have relied on steroids and a widely used anti-rejection drug called cyclosporine to maintain the islets’ survival. But recent studies have shown that cyclosporine actually kills the beta cells in islets. And the steroids promote insulin resistance in the body’s cells-the hallmark of Type 2 diabetes.

The Edmonton group circumvented these problems by using a trio of new drugs: sirolimus, tacrolimus and daclizumab. The first two are modified versions of compounds produced by bacteria, while the third is a specially prepared antibody that interferes with the rejection process. But because these drugs are so new, Sherwin cautioned, their long-term side effects are unknown.

Although the researchers used new drugs and more cells, the Edmonton group’s approach is similar to that employed by others. For each patient treated, the team uses two pancreases obtained from cadavers. Enzymes are used to free the islets from the bulk of the pancreas, and the islets are purified.

In a 20-minutes procedure using a catheter inserted through a small slit in the patient’s abdomen, the purified islets are infused into the portal vein leading to the liver. They lodge in the liver and almost immediately begin producing insulin in response to sugars in the recipient’s blood.

Insulin shots were discontinued immediately. One of the patients required a second infusion to achieve complete control of blood glucose, but all have remained insulin free.

“It’s not an immediate cure for all people with Type 1 diabetes, or anything close to that,” said Sherwin. “But this will be one of the key studies toward a final cure.

The paper is posted at https://www.nejm.com. Information about the forthcoming trials is available at https://www.jdf.org.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Breakthrough for Diabetics

Canadian researchers have successfully treated eight diabetics by using a new technique to transplant insulin-secreting islet cells.

*

Sources: Discover, The CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations