Cantinflas Lives Up to His Name

- Share via

When the Mexican comedian Cantinflas shunned the film companies of his homeland and signed with Columbia Pictures in 1946, he changed the course of Latin American cinema and lifted himself to international fame.

He starred with Frank Sinatra and Debbie Reynolds, won two Golden Globe Awards, including one for his role in the 1956 best picture, “Around the World in 80 Days,” all based on a simple character whose roundabout phrases and meaningless speeches confounded the wealthy and powerful.

Cantinflas, who died eight years ago, is still performing handsomely for Hollywood.

Last year, Columbia raked in an estimated $4 million in foreign distribution of the movies that Cantinflas, whose real name was Mario Moreno Reyes, made from the 1940s to the early 1980s.

But his tangled financial legacy is as confounding as any of his skits and with as many oddball characters. The studio, a subsidiary of Sony Pictures Entertainment, and Cantinflas’ son are locked in a court fight in Los Angeles for control of the most popular and profitable of those films. Columbia claims that it bought the rights to 26 films four decades ago, the result of a convoluted series of Cantinflas transactions through offshore bank accounts and a British holding company.

The case, which is scheduled to resume in Los Angeles this month, has stretched out for eight years and fills 47 federal court volumes. It involves missing documents, shifting alliances and death-bed jockeying by those closest to Cantinflas in his final days.

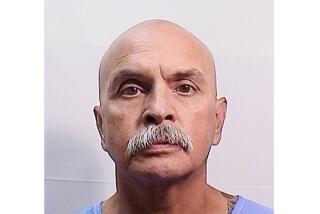

“We’re fighting for our rights,” said Cantinflas’ 40-year-old son, Mario Moreno Ivanova, on a recent trip to Los Angeles from his home in Mexico City. “I don’t want to see Columbia, this foreign company, get the rights or become the owner of a Mexican national treasure. These films were my father’s treasures--that he left me and that he left Mexico.”

It might be simple to solve if only Cantinflas could say what he intended. Or would it?

Reyes--the son of a postal worker and who unsuccessfully tried to sneak across the border into California when he was a youth--got his start in the 1930s in the dusty tent shows, the carpas, of Mexico City.

At first he tried to imitate Al Jolson by smearing his face with black paint. But the audience howled once he embraced his own Latin heritage as a lowly peladito, or slum dweller, a tiny mustache at the ends of his lip, a jaunty cap over his mussed black hair, a grubby vest and a rope for a belt, which sometimes failed to keep his pants up.

Cantinflas endeared himself to the masses by satirizing those with the most influence in Mexico: police and politicians. People identified with the struggles of the winsome ragamuffin and delighted in his talent. Cantinflas could talk his way out of any scrape with speech so florid--but so empty.

“Everyone went to see Cantinflas talking nonsense,” said film historian Gustavo Garcia. “He was famous for talking a lot and saying nothing. It’s an art--a Mexican art.”

The word “Cantinflas” has no meaning. But Cantinflas had such an effect on the Spanish-speaking world that his name became recognized by linguists.

The noun cantinflada is now defined in Spanish dictionaries as a long-winded, meaningless speech, and the verb cantinflear means to talk too much but say too little.

“To understand Cantinflas is to understand what happened in Mexico during the last century,” said Gregorio Luke, a film expert and executive director of the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach.

“Cantinflas, the character, is a unique consequence of the history of Mexico.”

David Maciel, head of the Chicano studies department at Cal State Dominguez Hills, said Cantinflas was “the single most important person in opening up Mexico to Hollywood. And then Hollywood just overran the Mexico cinemas.”

Luke and others say Cantinflas’ best films were some of his earliest, those made in the 1940s when he was poking fun at the social elite of Mexico. His wit was so foxy, his facial expressions so fanciful and his movements so fluid.

“He had this tremendous talent to make you laugh in many different ways,” Luke said. “It was Woody Allen meets Charlie Chaplin in Mexico.”

Cantinflas’ Legal Intent Is Unclear

In Los Angeles, after eight years and more than 950 motions filed, the federal court case could be called, well, cantinflada.

“We’ve been waiting for months and years and years and months just to get this case tried, just to get this case started,” lamented Senior U.S. District Judge William J. Rea last month.

The 81-year-old judge then smiled weakly and shook his lowered head. He chortled hoarsely, prompting the lawyers to wonder aloud whether he was laughing or sobbing.

Cantinflas’ financial transactions in the late 1950s and 1960s could provoke either.

The comedian and his movie producer-business partner set up several corporations and accounts in the Grand Cayman Islands and tiny Liechtenstein.

They moved the money from Cantinflas’ pictures through those accounts--presumably free from Mexican taxation.

No one is exactly sure what Cantinflas was up to.

“You and I would both like to meet [Cantinflas] in the netherworld or the next world and ask him,” said Virgil Mungy, a Chicago attorney who once represented Cantinflas but now is battling the comic’s son in a separate case in Mexico.

Columbia’s attorneys contend in court papers that the studio secured ownership of 26 films through some of those financial maneuvers in 1959, 1960 and 1968. Columbia says Cantinflas relinquished the rights to those films to get money to produce new pictures.

Studio officials say they have fulfilled their decades-old commitment to pay royalties to the actor and then to his tangled estate. Nearly $2 million awaits the family in an escrow account--money that won’t be dispersed until the case is resolved and Mexican courts settle a lingering dispute over whether Cantinflas’ son or his nephew inherited the films.

But there’s a glitch in Columbia’s case.

Neither Cantinflas nor his producer ever signed the pivotal March 1960 document that Columbia says completed the transfer of ownership of the films to the studio’s British subsidiary. Cantinflas’ name appears nowhere on the convoluted three-page document.

In fact, the document contains no signatures.

“The most important paper, the one that allegedly grants ownership to Columbia, is the one that doesn’t have Cantinflas’ signature,” said Moreno’s Pasadena attorney, Timothy C. Riley. That omission is reminiscent of Cantinflas’ signature phrase and the title of his critically acclaimed 1940 film “Ahi esta el detalle” (“That’s the Detail”).

Riley believes the transactions were nothing more than a vehicle to secure short-term financing for new Cantinflas films. Later documents indicate that the loan was paid off within three years, lifting the title cloud from the films, Riley says. Besides, he argues, Cantinflas and his shrewd Russian producer, Jacques Gelman, never would have given away the rights to Cantinflas’ most critically acclaimed films for 810,000 British pounds.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” Riley said.

Riley contends that Columbia is trying to rewrite history. He’s upset that Columbia gained access to the files of Cantinflas’ now-deceased lawyer in New York. And he’s still miffed that records were missing from some Columbia files he was allowed to inspect and that Columbia lawyers submitted, in the Mexican court case, revoked copyright certificates to show ownership of the films.

“You have to be sharp to protect yourself against these studio lawyers,” Riley told Judge Rea during a March 8 court hearing.

“It turns out, in fact, that some documents were missing,” Columbia’s attorney, Henry Tashman, told the judge that day. “We don’t know why; we don’t know how. But this is really quite irrelevant.”

But relevance is in the eye of the beholder.

Riley worries that Columbia’s team of attorneys--including one who served as a law clerk to Rea 10 years ago--will overwhelm the judge, who was first appointed to the bench by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan.

Cantinflas’ son points to what he calls another flaw in Columbia’s arguments. Moreno maintains that he--not the studio--has possession of the original film negatives.

He said he keeps the negatives in canisters in a tiled, climate-controlled room in Mexico City that his father had built to store the films. A laboratory technician comes to the house to dust and douse chemicals on the negatives to keep them fresh.

“My father always talked about Columbia as being the distributor of the films. He never, ever said the films had been sold,” Moreno said. “If my father saw this, he would die again--of anger.”

His Social Satire Was Lost on U.S.

“Down with the Curtain” (“Abajo el telon”) was Cantinflas’ 25th feature film, released in 1954.

By that time, Cantinflas was making pictures in Hollywood and starting to lose touch with his Mexican audience.

By the end of his career, in the 1970s and early 1980s, the comic who rose to prominence castigating the power structure was churning out pictures that were little more than propaganda pieces for the Mexican government, Garcia said.

“The real conflict of Cantinflas was his fight against his own character,” Garcia said. “He always wanted to be in Hollywood. But unfortunately, his humor was extremely local. In a way, he was betraying not only Cantinflas, but the audience who loved that character.”

His 1960 picture, “Pepe,” with Shirley Jones, a song by Judy Garland and a cast that included Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Zsa Zsa Gabor, bombed.

Cantinflas’ double-entendres in Spanish and social satire were not easily translated for an American audience. So the script, critics said, was reduced to tired racial stereotypes.

“Pepe” would end Cantinflas’ career in Hollywood, but by then he had achieved unrivaled status in Mexico and had begun hobnobbing with American celebrities. He helped arrange the wedding in Mexico of Elizabeth Taylor to her third husband, Michael Todd, producer of “Around the World in 80 Days,” complete with a fireworks display that spelled out the couple’s initials.

Cantinflas played host to President Johnson at his expansive ranch outside Mexico City.

Johnson sent a U.S. government plane to Mexico when Cantinflas’ Russian-born wife was dying of cancer to carry her to Houston for medical treatment.

And nearly 30 years later, when Cantinflas died, thousands braved a Mexico City downpour to file by and touch his closed casket, which lay in state. The presidents of Mexico, Peru and El Salvador attended his funeral.

But the years and weeks leading to his death were a behind-the-scenes scramble for control of the films or at least a chunk of the profits.

His longtime female companion in Texas sued in 1989 and obtained a $26-million settlement, which the octogenarian actor reduced two years later by agreeing to give her half of his share of the royalties from the pictures through 2000.

Less than two months before he died and in the midst of chemotherapy, Cantinflas signed an agreement that granted Columbia an additional 11 years of distribution rights for his final eight films.

That same day, he inked a deal to give his nephew the royalties from the films--a contract that was invalidated by Mexican courts. Still, the nephew renewed the lawsuit against Cantinflas’ son and Columbia Pictures. That case is still pending.

“My father was the center and everyone lived off him,” Moreno said. “Columbia knows that Cantinflas’ films are a gold mine--even though they say that people aren’t interested any more.”

Days before his father’s death, Moreno said, the family bickered in a Houston hospital over whether Cantinflas would die there or at home in Mexico City, which he did. Moreno says that fight was really about whether U.S. or Mexican law would rule in court--an issue still unresolved.

So “cantinflasque.” Just as the epitaph that Cantinflas himself offered from his deathbed eight years ago: “It would appear that he’s gone, but it’s (not) certain.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.