Work Draws on Years of Keen Observation

CLEVELAND — The first picture Charles Louis Sallee Jr. remembers drawing was of swimmers diving into Lake Erie at a Sunday school picnic. He was 4 years old.

Sallee, now 90, has been an artist ever since.

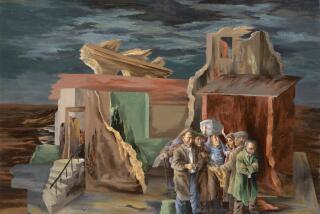

During his decades-long career, which began in the 1930s under the federal Works Progress Administration, Sallee recorded scenes of everyday events that would have been lost over time. About 20 of his works are being shown through Jan. 4 at the Artists Archive of the Western Reserve in an exhibition titled “Sitting for Sallee.”

“I don’t ever remember not being able to draw,” said Sallee, who grew up in Sandusky, Ohio. “When I look at something, I always think what it would be like to put it on a piece of paper.”

Sallee began his professional training when he received a scholarship to attend the Cleveland School of Art, now the Cleveland Institute of Art, in 1932, at age 20. Four years later, he became the first black person to graduate from the school, according to Alfred Bright, a professor of art at Youngstown State University.

But Sallee has little regard for such distinctions. He says he considers himself an artist and never liked the label “black artist.”

“Because, any artist is a representative of his personal environment, African American or otherwise,” said Sallee, whose work often captured the everyday lives of black men and women. “If you’re an artist, you start copying the things around you before you’re even interested in anything that’s away from you or different.”

In 1936, Sallee became one of almost 350 Cleveland artists hired by the WPA, the agency formed to provide work for people in Depression-era America.

He spent five years painting WPA-sponsored murals throughout the city. Sallee brought life to walls inside schools, housing projects, airport buildings and hospitals. He prided himself on murals that reflected the communities.

Many of his murals have been lost to decay or progress.

Bright said that one of Sallee’s most important murals, “A New Day,” was painted at Cleveland’s Outhwaite Homes, which was among the nation’s first federal housing projects. The mural, painted with soothing colors and soft edges, showed grateful children and their families being led from Cleveland slums to Outhwaite.

During World War II, Sallee went to Europe and the Philippines to draw tactical maps for the Army Corps of Engineers. When he returned in 1945, work in art studios remained scarce. But he needed to turn his talent to profit, so he took a job with an interior design firm.

He went on to spend nearly half a century in the business, eventually running his own firm, Sallee Associates Design Studio.

But his passion remains his portraits, his subjects animated by the ordinary actions of life, such as drawing a bath or dancing around a jukebox. His work has been exhibited in New York and at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

Although he no longer draws professionally, Sallee still has an artist’s eye.

“I look at people and I say, ‘Oh, they would make a beautiful oil painting,’ or, ‘They would make a beautiful watercolor.’ Some people can inspire you to the point that you can’t live until you’ve created them on paper.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.