Two Cities Compete for One Ethnicity

After decades of perceived indifference from its hometown of Westminster, the Vietnamese shopping district of Little Saigon is finally getting a pair of majestic city monuments to mark an official gateway to the ethnic enclave.

But the markers will be in neighboring Garden Grove.

The decision to place the concrete monuments -- one on each end of the designated zone, adorned with bamboo trees and the red-and-yellow South Vietnamese flag -- has touched off a turf war over which city has bragging rights to Little Saigon. The hot spot of tourism and business has expanded far beyond its two-block-long birthplace on Westminster’s Bolsa Avenue.

The controversy has revived a resentment harbored by Vietnamese merchants, who for years felt Westminster’s city leaders treated the area’s immigrants more as unwelcome guests than members of the community.

Also for years, Vietnamese leaders pleaded with the city to permit a privately funded Vietnam War memorial to honor those who served in the South Vietnamese and U.S. forces. The Westminster City Council finally relented, but only after Garden Grove expressed interest.

“Garden Grove has been very good for us. The city of Westminster, they’ve just been talking so long,” said Chieu Le, who owns sandwich shops in both cities.

Garden Grove Mayor Bruce Broadwater said it’s obvious that bustling Little Saigon has spilled across city lines to include the busy Garden Grove thoroughfare of Brookhurst Street, even if Westminster officials refuse to admit it.

“Little Saigon is expanding, and the Vietnamese population is expanding,” Broadwater said. “It’s not patented.... We’re not trying to steal anything from Westminster. We’re just trying to become a part of it.”

Leaders in Westminster, who officially recognized the city’s Bolsa Avenue corridor as Little Saigon in 1988, don’t quite see it the same way.

Westminster Mayor Margie L. Rice said the city has worked hard to cultivate Little Saigon since the mid-1970s, when it consisted of just three Vietnamese-owned businesses. Today, the cultural hub has more than 1,000 Vietnamese-owned retailers and professional firms, and has done much to raise the city’s profile.

“They can’t take Little Saigon,” Rice said. “Little Saigon is in Westminster. They can’t annex the city. They can put up the sign if they want. It doesn’t mean they own it.”

But Westminster Councilman Frank Fry Jr. said he’s not surprised to see Garden Grove courting Vietnamese business leaders. Westminster has always given them short shrift and “hates to put money into Little Saigon,” Fry said.

It took more than a decade for the Westminster City Council to allow landscaped medians along Bolsa Avenue, Fry said. Even then, there won’t be any signs identifying the area as Little Saigon.

“I’ve always fought for Little Saigon, but one can’t do it alone,” Fry said. “Westminster can’t get together on a floor plan for Little Saigon, so it’s frustrating to the Vietnamese.”

Fry spearheaded the proposal for the Vietnam War memorial, and said he nearly moved the project to Garden Grove because Westminster put up so many roadblocks. Westminster officials were afraid it would become a gathering place for demonstrations, he said.

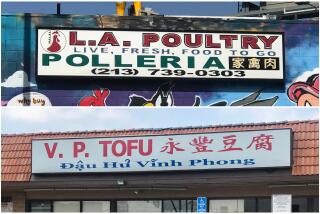

Garden Grove Councilman Van Tran said his city’s decision to promote its Vietnamese business district was common sense and long overdue. Vietnamese bakeries, video shops, grocery stores and other businesses dominate Brookhurst just south of the Garden Grove Freeway.

“It will promote economic vibrancy and put us on the map. Little Saigon is not so little anymore,” said Tran, who in the 1980s successfully lobbied the state to place directional signs to Little Saigon on the San Diego and Garden Grove freeways. “When you formulize a business or cultural area, the designation will heighten the awareness and prestige of the area.”

For visitors, Brookhurst has always been the gateway to Little Saigon -- even decades ago, when the district lay exclusively in Westminster. Plus, the latest U.S. census showed that more Vietnamese live in Garden Grove than Westminster -- 35,406 compared with 27,109.

On Tuesday, the Garden Grove City Council voted 4 to 1 to designate a strip of Brookhurst centered on Westminster Avenue as Garden Grove’s Little Saigon. The monuments, on the Brookhurst median about a half-mile apart, will greet motorists with “Welcome to Little Saigon, Vietnamese Business District of Garden Grove.”

The project will cost about $30,000, which will be raised by the Vietnamese business community. The monuments are expected to be installed in time for the Lunar New Year in February, the busiest tourist season of the year in Little Saigon as families gather for the holidays.

Garden Grove Councilman Mark Leyes, the lone dissenter in the approval vote, fears that the signs will divide the community and stoke ethnic tensions.

“It’s compartmentalizing or segregating a group of people,” Leyes said at the meeting, adding that he opposed a foreign language on the markers.

Chris Rae of Garden Grove, who has owned a business in the city for 25 years, also opposed the Little Saigon designation.

“I see it as potential ethnic problems,” Rae said during the council meeting. “It wasn’t one culture that started Garden Grove. Designating one area for one group causes problems and hatred. That should be everyone’s district.”

Still, the decision appears to enjoy widespread support.

Huzaisa Ismail, owner of the Little Saigon Produce and Al-Madinah Market on the corner of Brookhurst and Hazard Avenue in Garden Grove, said any merchant who doesn’t cater to Vietnamese residents won’t last long.

“First of all, if you’re not Vietnamese, it’s hard to make it here. That’s why I put ‘Little Saigon’ on my sign and have Vietnamese workers,” said Ismail, who emigrated from India in 1985 and is glad his market is included in the new business district.

A quarter-mile away, at Brookhurst and Westminster, the Vien Dong Superfood Warehouse stands where there once was a Ralphs supermarket. Lines form at Lee’s Sandwiches, where a Blockbuster Video had closed. A welcome sign in Vietnamese hangs on the Bank of America building.

“You have to know who your customers are,” Ismail said.

*

Times staff writer Ray Herndon contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.