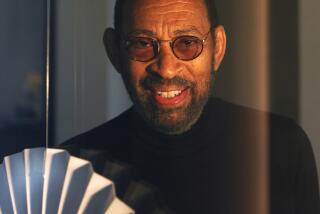

Maurice Gibb, 53; Singer With Disco Stars the Bee Gees

Singer Maurice Gibb, whose group the Bee Gees has sold more than 120 million records in a four-decade career that peaked with the disco music of “Saturday Night Fever,” died early Sunday at a Miami hospital. Gibb, 53, suffered a heart attack before undergoing emergency intestinal surgery Thursday.

The career of the Bee Gees -- Gibb, his twin brother, Robin, and their older brother, Barry -- has been marked by extreme highs and lows and an unusual knack for reinvention. They have had 15 top 10 records in the United States, including six consecutive No. 1 singles in the late ‘70s, and have won six Grammy Awards.

Their hits range from eccentric ‘60s records such as “(The Lights Went Out in) Massachusetts” and “I Started a Joke” to the songs that brought disco into mainstream culture -- “How Deep Is Your Love,” “Stayin’ Alive” and “Night Fever.” Most were marked by the brothers’ distinctive, three-part vocal harmony and catchy melodic hooks.

Praised during some periods for their originality and derided during others as kitsch, the trio recently has reaped career accolades, including induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997. Many of the Bee Gees’ songs have been revived by newer vocal groups, especially in England.

“Maurice Gibb was one of my favorite Bee Gees because his voice was so expressive,” Beach Boys leader Brian Wilson, who inducted the group into the Hall of Fame, said Sunday. “It made me happy and feel really good to hear him sing. His voice had a joy to it that touched one’s soul. On a personal level, I loved his sense of humor and his spirit. He was a real friend to me.”

Maurice (pronounced as “Morris”) was born on the Isle of Wight and grew up in Manchester, England, the son of bandleader Hugh Gibb and his wife, Barbara.

The three brothers discovered rock ‘n’ roll through their older sister’s records -- Elvis Presley, Everly Brothers and Bill Haley -- and began singing together, eventually entertaining audi- ences before films at movie theaters.

The family moved to Brisbane, Australia, in 1958. With their father managing their career, they performed at a racetrack and on radio and sang pop standards at nightclubs. They landed television appearances, but couldn’t manage any hit records. By the time a single, “Spicks and Specks,” became a hit in 1967, they had returned to England.

There they hooked up with manager Robert Stigwood, an associate of Beatles manager Brian Epstein, and recorded their first hit, “New York Mining Disaster 1941,” a folk-like tune sung from the viewpoint of a miner trapped underground.

The Bee Gees’ moody, orchestrated recordings -- “Words,” “To Love Somebody,” “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You” -- became a distinctive feature in the varied landscape of late-’60s British pop.

But dissension set in, and Robin left the Bee Gees (the name is short for the Brothers Gibb) for two years. During their early-’70s dry spell, they relocated to Miami and began incorporating R&B; into their sound. Recording at Criteria Studios with an Atlantic Records staff producer, Arif Mardin, they bounced back with the top 10 hits “Jive Talkin’ ” and “Nights on Broadway.”

When Stigwood shifted his RSO label’s distribution from Atlantic to Polydor, Mardin could no longer produce the Bee Gees, but two engineering staffers at Criteria -- Karl Richardson and Albhy Galuten -- took over and helped continue the new streak with “You Should Be Dancing.” They also oversaw the landmark “Saturday Night Fever” hits, which helped make disco an international phenomenon. The album sold more than 40 million copies, making it the biggest-selling soundtrack of all time.

Though disco formed just a portion of the Bee Gees’ history, they suffered from the genre’s decline in the ‘80s, a decade that brought them only one top 10 hit. The Gibbs also lost their younger brother, singer Andy Gibb, who died of a heart attack associated with cocaine abuse.

The Bee Gees themselves had weathered their share of drugs and drink. Maurice Gibb suffered from alcoholism for decades before going into recovery in the early ‘90s, after an incident in which he threatened his wife and children with a gun. His six-year marriage to pop singer Lulu ended in 1975; he later remarried.

In a 2001 interview, Gibb recalled his introduction to drink during the heady days of the group’s first success.

“We never even thought about the money -- we were just so excited about meeting the Beatles,” he said. “When we had it, we just blew it. I had six Rolls-Royces and eight Aston Martins by the time I was 21. John Lennon was the person who got me to drink my first Scotch and Coke. I was 17, and if he’d told me to take cyanide, I’d have done it. Before that, I’d only sipped a beer, but I liked what the Scotch did.”

But Gibb had another side, according to David Leaf, the author of the 1979 book “The Bee Gees: The Authorized Autobiography” and the writer-producer-director of a cable television documentary on the group, “This Is Where I Came In.”

“He was a down-to-earth guy, but he always had a real presence about him,” Leaf said Sunday. “He was really great with fans -- signing autographs, talking to them. He always had time for people.... He was an extremely kind person, very outgoing.”

He said Gibb’s contributions to the music are often overlooked. “Maurice was the showman,” Leaf said. “Barry was the frontman for the most part, but Maurice always gave the audience a great show. In terms of the record-making, he was the techno whiz of the band. He was the guy who got the latest piece of gear.... He would have been the one playing with the synthesizers in the early ‘70s.... I think that’s a big reason why Bee Gees records always sounded contemporary. When it came to the instrumental sound, the beats, he had a big hand in that.”

In recent years, Gibb had become an enthusiast of the game paintball, leading a team called the Royal Rat Rangers and opening a Miami paintball goods store.

The Bee Gees’ latest album, “This Is Where I Came In” in 2001, marked a return to acoustic instruments and simple, naturalistic production. The fact that the group’s ‘90s albums had sold little in the U.S. didn’t seem to faze Gibb during a 2001 interview with The Times.

“This is what we love to do,” he said. “If you’re a writer and you win the Pulitzer Prize, you don’t stop writing. If you’re a scientist and you win the Nobel Prize, you don’t say, ‘Now I don’t have to do science anymore.’ It’s born in us, we’ve done it all our lives.”

In addition to his brothers Barry and Robin, Gibb is survived by his wife, Yvonne; two children, Adam and Samantha; and a sister, Leslie.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.