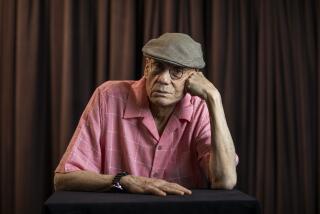

O’Lear knew pickpockets inside-out

Whenever I think of Oscar O’Lear, I think of Timothy Mittens. Mittens was a pickpocket and O’Lear was a pickpocket cop, so their association, you might say, was semiprofessional.

I don’t know what Mittens’ real name was. They called him that due to the fact that years before, a judge had sentenced him to wear mittens in public places because he had been caught so many times practicing his trade.

Mittens had asked the judge what he considered to be a public place. “Every place is a public place,” the judge replied, “except your house, my house and the court clerk’s house.”

He never did wear the mittens, and one day O’Lear saw him in a department store and arrested him. “Hey, man,” Mittens said, “I wasn’t doin’ nothin’, I was just passing through.”

“I know you weren’t doing anything,” O’Lear said. “I’m arresting you for not wearing your mittens.”

I never knew Timothy Mittens, but I knew a lot about him. I did know O’Lear pretty well, and he was one of a kind. His relationship with the Mitt, as he called him, was one of the anomalies of the street, where guys on different sides of the law could understand each other, and almost be friends.

The reason I am writing about O’Lear now is that his daughter, Colleen, informed me that her dad died the other day. We carried a nice obituary, with a picture, but obits rarely define the essential person.

I met O’Lear in the mid-’80s, after he had retired from the LAPD, in which he’d served for 28 years as, quite possibly, the best pickpocket cop in America. He was working freelance at Hollywood Park, searching for spears, which was one of his names for pickpockets. They are also called grifters, dips, stick men and lone cannons.

“You look for abnormal actions,” he explained as we wandered through the crowds. He was dressed in urban camouflage, which is to say nondescript clothes, and his gaze was as intense as a laser beam when he locked on to an abnormality: “Everyone is watching the race except for one guy who’s watching the mark,” he said. “That’s the one you want.” The mark is the victim. The guy watching him is the dip.

“Sometimes,” O’Lear’s partner said to me once, “the mark is watching the race, the pickpocket is watching the mark, Oscar is watching the pickpocket and I’m watching Oscar. We’re like a parade.”

They called him O’Leary, with a “y,” on the street. He slouched slightly when he walked, scowled a good deal of the time and knew more about pickpocketing than most people want to hear.

That day we cruised the crowds at the track he told me how the crime went back to the Romans and maybe earlier. He had traced it to 16th century England, he said, where they used to hang pickpockets in public. “But you know how effective that was?” he asked. “Pickpockets love crowds, so they worked the public hangings!” He shook his head, almost but not quite smiling. “Can you beat that?”

O’Lear busted a guy once who claimed to be an astrologer. When the judge was about to sentence him, the man offered to read the judge’s horoscope. “No,” the judge said, “but I’ll read your future: Two years in the state pen and two years on probation.”

O’Lear was full of stories, including one about pickpockets who were called dunnigans, or toilet spears. They hit marks who were less likely to give chase. O’Lear could imagine someone trying to pull up his pants and go after a pickpocket at the same time. It almost amused him.

He talked about Timothy Mittens the most. Once he returned early from a trip and busted the Mitt for doing his thing. The guy looked at O’Lear and said, “What’re you doin’ here? You’re supposed to be on vacation.” O’Lear observed him with a Walter Matthau scowl and said, “I came back because I missed you.”

O’Lear arrested Mittens’ son and daughter on separate occasions. They were trying to follow in Papa’s footsteps. It made both men sad. “I don’t want them to do that,” Mittens told O’Lear, who replied as gently as he could, “That’s what happens when the father does it.”

What bound them together, O’Lear used to say, was an incident that occurred on the day he retired from the L.A. Police Department. O’Lear had been having problems with the chief and they didn’t give him a retirement dinner, despite 28 years on the force.

“But you know who comes down to buy me a cup of coffee on the last day?” he asked rhetorically. “Timothy Mittens.”

O’Lear was 86 when he died of natural causes. He didn’t want any kind of memorial service, but I know that somewhere, if he’s still around, Timothy Mittens is having a cup of coffee in his honor. O’Lear said to me once, thinking about their friendship, “Funny place, the street.” And a little lonelier now without him.

*

Al Martinez’s column appears Mondays and Fridays. He’s at al.martinez@latimes.com.