Politics Makes a Strange Friendship

DES MOINES — Joe Trippi makes a confession: If Howard Dean’s national campaign chief could team up with just one battle-tested political insider in the war to unseat George W. Bush, it would be the guy in the red tie sitting next to him in this midtown coffee shop -- Trippi’s old friend, Steve Murphy.

It’s a strange choice, because Murphy is national campaign manager for Rep. Dick Gephardt of Missouri, who’s in a tense, take-no-prisoners struggle to defeat Dean and Sens. John F. Kerry of Massachusetts and John Edwards of North Carolina in today’s Iowa caucuses.

But that doesn’t stop Trippi. “If I could have Steve Murphy with me in the trenches,” he says, “I’d dig the trench myself.”

They’re the odd couple of presidential politics. Oscar-and-Felix style adversaries facing off in the biggest bout of their careers. And while the stakes are high, for Trippi and Murphy the fight is nothing new.

During the last 25 years, the two campaign gypsies often have worked on opposite sides in Democratic presidential campaigns, and an intense one-upmanship partly defines their relationship. But in a cutthroat business, where Trippi says “you make enemies for life,” these two have stayed friends.

They met on Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1980 and worked side by side for Gephardt here in Iowa during his 1988 bid for the Democratic nomination. Even on the same team, they fought like teenagers, one always looking over his shoulder to make sure the other didn’t get any favored treatment.

Like the candidates they now represent, their styles are a study in contrast: Trippi’s sharp elbows against Murphy’s steely reserve. Trippi wanting to be different just for the sake of it versus Murphy’s pound-it-out, conservative game plan.

At 47, Trippi is a high-stakes gambler who hit the jackpot this year with a strategy to use the Internet as the youth-fueled engine for the Dean campaign. A stock day trader in his off hours, he’s a human factory of risky, off-the-wall ideas -- a fast-talking dervish with a rumpled shirt and messy hair who downs a dozen diet Pepsis a day and talks around the pinch of cherry Skoal tobacco lodged in his cheek.

Compare that to Murphy, the hyperorganized steady hand who looks like an aging frat boy with his hard gray eyes and a hair-trigger temper. In his crisp tweed jacket, he’s an often-brooding figure who speaks softly with a slight Delaware inflection -- the kind of manager who prefers to listen before he speaks. But when he has something to say, subordinates lean in close. Friends say Murphy’s a breeze to get along with -- as long as he’s in charge. The campaign has caused him so much heartburn that he recently kicked his four-cup-a-day coffee habit.

“If we shared a firm, I’d be the one in charge of keeping the office clean, that’s for sure,” says Murphy, a 52-year-old father of two with a third on the way. “Joe would be in charge of losing all our profits through day trading.”

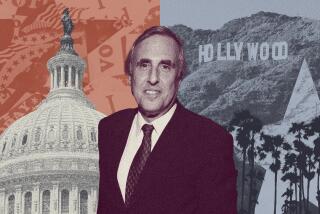

Born in upstate New York but raised in Hollywood, Trippi schmoozes people like a movie pitchman. He loves the glitz and pursued an aerospace engineering degree at San Jose State University before becoming distracted by politics.

Murphy was a small-town boy from rural Delaware who studied sociology at the state’s university. He spent time working for Volunteers in Service to America to clean up an inner-city New York neighborhood before going to Mississippi for Jimmy Carter’s 1976 presidential campaign.

Both on their second marriages, Trippi and Murphy share a lust for presidential politics -- an outright addiction to the high-wire, without-a-net tightrope walk where the risk of very-public failure always looms. It’s a precarious place with little room for personal ties.

“Hey, both Steve and I know the rules out here,” Trippi says. “He’d roll me in a second. And I’d do the same to him.”

With a combined 10 presidential races between them, most competitors remain wary of meeting either Trippi or Murphy in a dark campaign alley.

“The difference is getting hit by Murphy’s surgical stiletto or Trippi’s overkill meat ax,” says David Axelrod, a media consultant for Edwards’ campaign. “Either way, you’re dead.”

Yet over the years, after the last campaign volunteer has left for the night and the bottle of bourbon is pulled from the drawer, a reflective Trippi and Murphy have looked to each other for sibling-like solace and pep talks, not to mention outright mockery and gut-punches.

They’re not the kind of friends who go to baseball games together, but they seek each other’s counsel at critical times. “Before I decided to start my own firm in 1990,” Murphy says, “Joe was the first person I called for advice.”

Murphy was a successful Washington media consultant when he agreed in December 2002 to run the national presidential campaign of his old friend -- Gephardt.

It was risky to leave the comforts of home for unfurnished apartments, soulless hotel rooms and obsessive 20-hour days. A political campaign is the domain of 25-year-olds, Murphy says, not men twice their age. “If my colleagues in the consulting business didn’t laugh at me, they certainly smirked.”

One of those laughing was Trippi, who co-owned a Washington consulting firm. He called Murphy to razz him. A month later, Trippi got his own call from Dean.

“One part of me was flattered,” Trippi recalls. “But another voice said, ‘God, man, don’t do this!’ In the end, I figured that if Steve was crazy enough to do it, I could, too.”

With the race in full gallop, the pair talk less often -- unless you count the profanity-laced voicemail message Murphy left Trippi after Dean had slammed Gephardt in a recent debate on affirmative action. Murphy says he saw Trippi’s leering face behind Dean’s charges.

The biggest threat to their friendship came in 1990, when, as a media consultant, Trippi beat out Murphy to represent a Democratic candidate in the Iowa governor’s race. Murphy thought Trippi had stolen a client. The pair didn’t talk for five years.

“I thought what Joe did was inappropriate among friends,” Murphy says.

They reconciled after Trippi apologized. “My partner got us in the same room and brokered the deal,” Trippi says. “He said, ‘Tell Murphy you’re sorry. This is ridiculous. You two guys love each other.’ ”

The other day, the two agreed to meet for coffee to show that the “love” -- not to mention the fierce competition -- carries on.

“Joe’s not the kind of guy who’d ask out your girlfriend when you were out of town,” Murphy says at one point. “He’d do it while you were still in town.”

Trippi shoots back: “I’m amazed at what Murphy has accomplished with Gephardt. He’s done everything he could to take fourth place in the Iowa caucuses.”

Behind the barbs, a mutual respect lingers. Murphy says his worst day in the last year was when he found out Trippi would run Dean’s campaign and become his outright opponent.

Both call this campaign their last. They wouldn’t do another grueling race like this, even in the same camp, even if the other called to beg. But, then again, they’ve both said that before.

But now it’s back to business. Trippi’s hand-held computer buzzes nonstop with staff e-mails as Murphy tries to look the other way. He wants so badly to win that he can taste it. And if you’re going to win, you might as well do it at the expense of a consummate player like Trippi.

“Both Joe and I will do whatever it takes to win for our candidate,” he says. “And we’ll allow nothing, not even our friendship, to get in the way.”

If either of their candidates prevails in the Democratic primaries, both expect a congratulatory call from the other. For now, though, Murphy’s strategy in Iowa comes from an idea that Trippi dreamed up 16 years ago: “But I’m not going to say what it is, because I’m still using it and he may have forgotten.”

Trippi’s eyes widen before he leans back, pleased with himself.

“I know what it is,” he whispers. “But I’m not saying either.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.