The patron saint of chick lit

We live in a Jane Austen universe. A book about a book club that reads only Jane Austen is firmly entrenched on bestseller lists. Keira Knightley, one of Hollywood’s reigning “It” girls, is filming yet another version of “Pride and Prejudice.” Elizabeth and her beloved Mr. Darcy are living out the married chapter of their lives in “Mr. Darcy Takes a Wife: Pride and Prejudice Continues” at bookstores. We can buy Pride and Prejudice, the board game, and Jane Austen paper dolls. Jane Austen, the sleuth, has her own line of mystery novels.

Austen, it appears, is our new Shakespeare. Two hundred years after her novels were written, she’s ascended to that level where her work is imitated, quoted, ripped off and, yes, revered. Citing Jane these days is like playing a smart card.

“There’s always been a need in people to have something that cues smart, or well-read,” says Robert Thompson, a Syracuse University professor specializing in popular culture. “It tends to be Shakespeare. It’s something that is immediately read as ‘I’m smart, I’m well-informed,’ which is usually done to play against expectations. As in, ‘I may be a flighty blond, but I can recognize a Rembrandt.’ ”

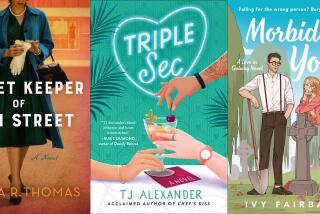

Nowhere is this more evident than the large chain bookstores, where “chick lit” tables are smothered with volumes boasting an Austen reference in a blurb on the back cover. Austen, it’s been suggested, is the great-great-grandmother of chick lit -- that exploding genre about upwardly mobile young women and their wayward travails through the world of modern courtship (and shopping), set mostly in the best neighborhoods in London or New York.

Hmmm. That does sound suspiciously like Austen: privileged women, privileged environs, an obsession with material wealth and class distinctions, and, always, the underlying mating dance.

But before we go too far, let us now state, up front, that if Ms. Austen ever got her otherworldly self a copy of “Confessions of a Shopaholic” (wildly popular chick lit by Brit Sophie Kinsella), she wouldn’t necessarily consider it a tribute. Her heroines may have their flaws, but in chick lit, short supplies of geographical intelligence, financial prudence and some basic common sense seem to be common afflictions. Call it Jane Austen Lite.

“The references to Austen that any of us make are a way to try and say a book that concerns young women and courtship needn’t be idiotic,” author Darcy Cosper says. “But I definitely think we take Jane Austen’s name in vain.”

Cosper, 34, a smart and serious Austen reader, set out to subvert chick lit (she hates that term) and the importance it places on getting The Man. Her heroine in “Wedding Season” rejects the right guy because he demands all or nothing -- and she decides marriage just isn’t for her.

The book can now be found on chick lit tables nationwide. The comparison, it appears, is unavoidable. Where did all this come from? What suddenly made Austen so unbearably hip?

Michael Gamer, a University of Pennsylvania professor who teaches a class about Austen’s translation to other media, dates the beginnings of the transformation to a World War II-era renewal of interest in her work (Hollywood’s 1940 version of “Pride and Prejudice” starred Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson). But the big turning point came with the onslaught of films near the end of the 20th century, he says.

“It’s really only been in the last decade or so that Austen has become a truly popular novelist that everyone reads and knows about,” Gamer says. “Something happens when you put Austen on the screen or when you repackage Austen for a film audience. It transforms the novels.”

The Brits rediscovered Austen first, filming most of her novels in the 1980s. In 1995, Hollywood made “Sense and Sensibility” and “Persuasion” into films.

Then came Colin Firth. His appearance as Mr. Darcy in the 1996 BBC version of “Pride” was a phenomenon. Women played the video again and again, as do the characters in British author Helen Fielding’s popular “Bridget Jones” books, one of which openly riffs on “Pride,” right down to The Man bearing the name Darcy.

In 1996, perky Alicia Silverstone played an Emma-like character in the fun, sharp “Clueless”; Gwyneth Paltrow played Emma in the eponymous 1997 movie. “Mansfield Park” made it on screen in 1999.

Audiences took to the movies for the romance, but Austen also appeals and resonates -- as Martin Amis pointed out in a 1996 New Yorker article -- because of her sharp rendering of class and class distinctions. Modern life may not be overtly stratified as it was in Regency England, but a sense of status and place is still an essential underpinning. Witness the wild success of “The Nanny Diaries” and “The Devil Wears Prada,” novels that expose the excesses and obnoxiousness of America’s reigning class through the gaze of what is, essentially, the servant.

“There’s a host of reasons ‘Why Austen? Why now?’ and they’re all speculative,” Gamer says. “It’s a complicated question.”

One answer comes from someone who is an Austen expert only in that she has read the canon countless times. “Austen,” says Nell Minow, editor of a corporate governance website, “has a stunningly modern sensibility. And it took the rest of the world a couple centuries to catch up with her.”

To categorize Austen as simply a writer of romantic fiction is foolish. Austen is cynical where most romance is hopeful; her characters are often deeply flawed. Her world may be, on the surface, one of cottages and vast lawns, but it’s really an interior world, one she renders unsparingly, with a masterful level of social observation.

What Austen did, Gamer explains, is “adopt traditional relationships of romance into a more radical framework.” Her novels keenly observe and strongly critique a time in which economic circumstances and rigid class restrictions limited women’s choices. In the end, the only real choice was marriage, hence the sardonic version of the traditional marriage plot, with the heroine swiftly married off in the final pages.

“One of the things that is appealing about the novels is that they get at the predicament young heterosexual women face when they live in an age that frankly penalizes any real radical behavior,” Gamer says. “So her heroines are, for the most part, smart women who are often compelled to spit tacks at the folly around them but don’t really have a lot of options except to change from within.”

In chick lit, the marriage plot is alive and well. But what’s usually lost is Austen’s ability to resolve a courtship filled with excitement and witty repartee into a union that seems less a marriage than a merging of well-matched minds.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.