Marine Lance Cpl. Felipe de Jesus Sandoval-Flores, 20, South Los Angeles; Among 6 Killed in Iraq Flood

The calls always came early Saturday mornings, from wherever he was stationed in Iraq. Marine Lance Cpl. Felipe de Jesus Sandoval-Flores would phone home to tell his family that he was doing fine.

“He’d always say, ‘I’m OK. Things are OK,’ ” recalled his older sister, Blanca.

On April 1, the call came earlier than usual, about 5:30 a.m., at the family’s home on 91st Street in South Los Angeles.

As always, his sister said, her brother assured everyone that he was fine. But he also said he was tired.

The next night, about 10:30, there was a knock on the door. “Once we saw three Marines,” his sister said, “we knew something was wrong.”

Sandoval-Flores, the family learned, was among six Marines killed April 2 when their 7-ton truck overturned in a flash flood near Al Asad, west of Baghdad.

He had been in Iraq two months.

Sandoval-Flores had long imagined becoming a soldier.

“Even as a child, he dreamed of going into the military,” his sister said.

Born in Michoacan, Mexico, Sandoval-Flores, 20, was the second of five children born to Toribio Sandoval and his Salvadoran wife, Carlota Flores.

Outgoing and athletic, Sandoval-Flores was always engaged with family and friends.

“He was a guy who cared for people, and if he really cared for you, he would guide you in any way he could,” said longtime friend Cesar Flores, 19, who had known Felipe since the eighth grade.

At Locke High School, Flores played wide receiver and Sandoval-Flores was a wiry defensive end. Around campus, everyone knew Felipe as “Phill,” the class clown who was always quick with a joke and drove a black 2001 Camaro convertible.

If he had a dream beyond the military, it was to become a police officer, a goal he was sure would be facilitated by a stint in the service.

“He said he was never the college kind of guy,” Flores said. “He thought it would be an easier way for him to join the police” after serving in the military.

A few months before his high school graduation, Sandoval-Flores enlisted in the Marine Corps.

“Before he signed up, we all sat down as a family and discussed that the country was at war,” his sister said. “We said there was a really big chance he would go to war and how much it would hurt for us to be apart from him. But he said, ‘This is my dream [to join the service].’ He was never afraid about going to war.”

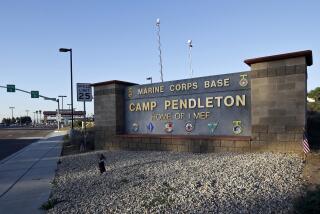

One month after earning his diploma, he was off to basic training at Camp Pendleton. Eventually he was assigned to the 1st Marine Logistics Group, 1st Marine Expeditionary Force.

“After graduating from boot camp and when he said he was going to Iraq, we sat down again as a family,” his sister said. “My mom was literally begging him not to go, and he said, ‘I want to go. Mom, don’t worry. I will be OK.’ ”

As surely as he tried to calm his family and friends, Sandoval-Flores certainly knew the danger he was facing. But he always made it clear that he never feared dying.

“The single and most prevalent fear of most men is death,” he wrote for his high school English class just months before he graduated.

His essay, somber and filled with references to Scripture, underscored Sandoval-Flores’ recognition, even as a teenager, that, as he wrote, “Tomorrow is never promised.”

The essay ends with this: “Death scares me, but it is coming, ready or not....”

Looking back, his sister said she believes the serious conversations that she and her younger brother often had were meant to prepare her and the rest of the family for the worst.

A devout Catholic, Sandoval-Flores may have been prepared for death, but he also embraced life, family and friends said.

“Felipe was always a giving kind of person, a good heart,” said another longtime friend, Raoul Gonzalez, 22.

Whether it was letting friends win at video games, counseling young parishioners on the Catholic rite of confirmation or helping out the homeless, Sandoval-Flores savored every day, Gonzalez said.

Once, Gonzalez remembered, the two were out distributing food, clothes and hot chocolate to the poor when Sandoval-Flores spotted a boy about 9 or 10 years old in line with the others.

“Felipe had this new sweater, not even 2 weeks old, and when he saw this young kid, he didn’t hesitate, he took off his sweater and gave it to him,” Gonzalez said.

At his funeral, more than 200 family members and friends watched Sandoval-Flores’ body carried to his grave at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City by a white carriage drawn by two white horses.

“Words cannot explain how much we miss him,” his parents wrote in a letter to The Times. “We are proud as [his] parents because, despite being poor, we were able to raise a good young man with a big heart who loved and respected his fellow human beings.”

In a separate letter, his younger sister, Michelle, wrote: “April 2, 2006, I recognized true sorrow; my brother was not coming home.”

But through the pain, she wrote, “I am glad Felipe is no longer living in that hell called war.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.