Feeling extra ordinary

“DO you want false eyelashes?” asks Rocky Faulkner, a tall, lean makeup artist wielding a mascara brush.

I’ve been enlisted as a foot soldier -- an extra -- in the army of glamour assembling for what might be the most glamorous film of the Christmas season, the big screen version of “Dreamgirls.” These days, movies often arrive with the stink of studio-manufactured buzz clinging to their trailers, but the film of this legendary Motown musical has been generating wanna-see excitement ever since a snippet of footage wowed journalists in Cannes.

Perhaps the draw is the fact that much of the African American showbiz aristocracy has assembled in one movie -- Beyonce Knowles and Jamie Foxx, Eddie Murphy and Danny Glover, and popular “American Idol” finalist Jennifer Hudson. Perhaps it’s the enduring resonance of the classic showbiz story about the birth of a star, and the collateral damage left in the wake. Unlike some other musicals trying to crossover to the screen, “Dreamgirls,” the fictionalized telling of the rise of Diana Ross and the Supremes, which opens Dec. 21, doesn’t seem dated, although it will be 25 years since the Michael Bennett production first opened on Broadway.

So there I was at close to midnight on a soundstage in downtown L.A. this April, and I’d spent the last hour getting primped. For an extra, the beautification process has all the psychological satisfaction of being turned into fancy wallpaper.

I’ve been outfitted in a blue silk shantung gown by Amy Glenn and Devon Anderson, who estimate they’ve provided some 6,000 costumes for the show, and I’ve had my hair curled by Jazz Kimbel, one of a dozen or so hair stylists assigned to do the “background” -- the extras. Kimbel, whose daughter, Kimberly, does Knowles’ hair, explains that tonight’s scene takes place in Vegas, late in the rise to stardom of the Dreams -- the group composed of Knowles, Hudson and Tony Award-winner Anika Noni Rose. “It’s a more upscale Caucasian crowd. A lot of up-dos. A lot of people using their own hair. That was such a wig era -- especially with black people,” she explains.

Soon, I’m ushered to the main stage, where Caesars Palace, circa New Year’s Eve 1966, has been re-created, a lavish over-the-top montage of midnight blue and gold and diamonds. The look of the $70-million movie has been toned down compared with what actually was going on in the ‘60s and ‘70s, says producer Laurence Mark, because “if you actually do the ‘60s and ‘70s exactly as they were, you run the risk of spoofing them. We calibrated to make them more appealing.”

Tonight is the second to last night of shooting, and this is the moment when Hudson will be doing her pivotal song after her character, Effie, learns she’s getting pushed out of the girl group by her manager and lover. Effie declares, “I’m telling you, I’m not going,” and the filmmakers plan on dissolving from Effie’s lament into the new Dreams -- sans Effie -- striding out on stage singing a snippet of the song “Love Love Me Baby.”

“Bam, there’s a new group in not even a blink of the eye,” says Mark. “It’s our version of special effects without really doing special effects.”

This key moment shoots late in the schedule because “we wanted to give her as much time as possible to find her sea legs and get confident,” Mark says. As the camera crew sets up, Hudson floats through in a pink sweatshirt, carrying a video camera. She tells one of the cast members that she’s recording the experience for herself because she doesn’t want to forget.

THE DIVA REHEARSES

KNOWLES wanders in for rehearsal with a black bathrobe over her long sequined turquoise gown, hair piled up on her head, long manicured nails and false eyelashes so big that when she blinks it’s reminiscent of a sleeping cartoon lion opening one orb to spy on his surroundings.

Writer-director Bill Condon, who at 51 remains disconcertingly elfin and youthful, adapted the Tom Eyen book and has given the movie more of a social-political context than the stage show. There also are four new songs, written by Henry Krieger, who wrote the original musical with lyricist Eyen, with some added help on one crucial song from Scott Cutler, Anne Preven and Knowles.

As an extra, my job is to simply pose as a Caesars Palace patron. I’ve been given a primo seat up close to the stage at the juncture of two dolly tracks. The camera is going to zip from left to right and then backward. It’s a little bit like sitting at a railroad crossing; you can feel the trail of wind as the camera operators whip by. There are also gigantic, floor-to-ceiling firework sprinklers, which explode like a fire fountain when the women actually come out on stage. The extras at my table appear to have wandered out of Ricky Gervais’ HBO show “Extras” -- they really do discuss things like how to accumulate enough working hours to get Screen Actors Guild cards. One woman, whose task today is to sit in costume at the table and watch the show, insists, “I’m a team player when it comes to filmmaking.”

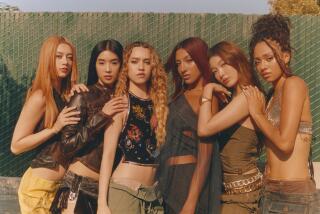

A complicated musical like this is possible only with lots of rehearsal -- about two to three months’ worth, and down on the stage, Knowles seems to have subtly taken control of what she, Rose and Sharon Leal (playing Michelle Morris, who replaces Effie in the group) will perform. It’s not as if the pop diva is bossy or impolite (in fact, she carries an aura of sweetness), she’s just focused. She relentlessly practices a move that will constitute some 20 seconds of film. The trio, all now wearing turquoise sequins, are to burst through from the back of the stage singing and proceed in unison down the proscenium stage to the end, where they finish with an iconic profile stance, almost like Motown’s version of King Tut.

Knowles, who has now been adorned with a long wispy scarf, is determined to get this tiny moment right. She snaps her arm and wrist some 50 to 100 times trying to perfect the hand movements for the strut down the stage.

“It’s broken wrist?” she asks Fatima Robinson, a hip-hop specialist who won a contest to choreograph the film. Knowles demonstrates a lyrically bent wrist. Robinson has brought along two assistants, and at one point each choreographer takes one of the actresses and practices the gestures, the walk, the stance at the end. As one of the assistants sits down to watch, he notes, “They’re going to just keep doing it because they’re not comfortable yet.”

ROLLING

AT 3:02 a.m., after all the makeup retouches and rehearsing, Condon and his team finally begin to shoot. The women burst out singing “love, love, love,” the cameras converge and the fireworks shoot off. Rose, Leal and particularly Knowles have amped up their energy even further. To a layperson, it looks and sounds amazing, but Knowles is not satisfied. “It was better,” she says, but “it was still....” She doesn’t finish her sentence, just wrinkles her nose dismissively. There are beats that apparently haven’t been hit properly.

They continue to perform take after take, with Condon coming down from his perch up in the back of the soundstage to adjust the camera movement. The fireworks leave an acrid smell in the auditorium. Hudson won’t get to do her big moment until daybreak, after which the day’s shooting ends.

Around 4, I leave. My last vision is of Knowles, ethereally beautiful in her sea foam gown. She’s scowling. The entire “Dreamgirls” team, all 150 or so cast and crew members, begin another take.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.