He taught tap -- and life

Looking out at the crowd gathered in front of him, dancer Channing Cook Holmes struggled to describe the singular magic of his late mentor, Alfred Desio. But he couldn’t recall what he intended to say as he stood fighting back grief, clad in a neat gray suit, smart yellow tie ... and stocking feet.

So he slipped on a pair of shoes and started dancing.

That’s what happens at a memorial for a tapper.

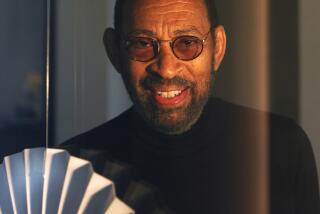

On Sunday, Holmes and about 150 other people answered the call of their personal pied piper one last time and trooped to Zipper Hall at the downtown Colburn School, where Desio, 74, taught life as well as tap before succumbing to cancer last month. Like me, they came to remember not only a great hoofer and instructor but also a friend.

A onetime child prodigy back East, Desio enjoyed a solid Broadway career before moving to Los Angeles and making his name as a teacher and performer -- and as the guy who figured out how to enhance live tap sounds with a synthesizer in real time, a brilliant engineering feat that became part of the movie “Tap.” That innovation, of which he was ever proud, will be regarded by some as Desio’s unique legacy.

But to my mind, the dazzling sound effects somewhat obscured the purity of his virtuoso dancing. He ranks among the most technically precise and dexterously advanced tappers I’ve ever seen.

Those in attendance Sunday got a sweet taste of Desio’s dancing on tape, courtesy of Louise Reichlin, his widow, who herself runs a modern dance troupe. Among the gems was “Brandenburg Boogie,” a hip arrangement of Bach that Desio choreographed into a classic. And there were selections from “Caution, Men at Work: TAP,” his answer to Australia’s Tap Dogs.

Sunday’s event quickly became a live show, a gratis Desio alumni shindig. It included 23-year-old twins Sean and John Scott, who regularly dazzle crowds on the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica. Ten-year-old Joshua Villanueva and Rachel Rosenbaum, 14, performed portions of the Brandenburg piece, just as they had with Desio during his final, gutsy performance last May.

It was true to form for Desio to extend himself in sharing his art form. He made regular pilgrimages to hardscrabble urban schools, carrying Velcro strap-on taps for demonstrations. His own performing ensemble became a kaleidoscope of ethnicities and backgrounds.

One parent spoke of the utter, attentive respect he would show the youngest children. The mothers and fathers of first-time students would watch -- perplexed, amazed -- as Desio sometimes taught an entire class without saying a word. He’d start moving with a certain cadence, a discernible repetition. Pairs of clattering feet did the same. If he added a brush, so did they. Then the music would change. He’d start clapping, then stop after three counts. So did they.

“I probably do it that way to not get too involved with describing things,” he said a few years ago, “but to try to sharpen a student’s visual skills -- to be able to look at something and duplicate it, or listen to something and duplicate it.” Later in the class, he’d often spread out string instruments, drums, castanets, blocks and keyboards and let the children discover musicality.

When his students approached adolescence and developed attitude, Desio readied for war. His patience grew short, his demands long. He was fighting for them, to get them to the other side as gifted dancers and responsible adults. “I won’t give them an inch,” he said, especially if they wanted to join his company, the Colburn Kids. “To the girls, it’s ‘Knock it off with the bare midriff.’ To the boys, it’s ‘No belts hanging off in front of your pants.’ If I see a nose ring and multiple earrings, I’m going to comment on it.”

Ever the perfectionist, he’d lose his patience with me too, despite my generally solid adult behavior. But he also treated me to stories. He’d show me the tap shoes he kept for needy students and his cache of obscure metal taps from generations ago, which he collected for his own amusement. It was hard to imagine anything slowing down this diminutive, seemingly ageless athlete. “We never looked back,” Reichlin said at the memorial. “Only present and forward.”

For many, the show/ceremony could never be simply about Desio. It also had to recognize his partner in artistry. “He and Louise together taught me the value of hard work and rehearsal, and rehearsal, and rehearsal again,” said M’saada Nia, now a filmmaker, who hadn’t put on tap shoes for seven years before rehearsing for this memorial with pals Gina Nicholson and Myshell Curry, now a teacher at Colburn. Nia recalled how Desio provided her with free shoes and free lessons when she couldn’t afford them. “I have something valuable,” she said, her voice breaking, looking at Reichlin. At that moment, she wasn’t talking about tap. But when the time came, so did the footwork.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.