Terror, latex flow at Firestone plantation

HARBEL, LIBERIA — They come in broad daylight, with guns, machetes, knives and buckets of acid.

The invaders of Bridgestone Firestone North American Tire’s rubber plantation in Liberia are hunting what they call “elephant meat”: To them, the company is so big that anyone can take a hunk of flesh and no one will notice.

Some people who stand in their way get hacked to death. Others, such as William Brown, a 42-year-old security officer, have had acid hurled on their face and bodies.

During 14 years of civil war in Liberia, the plundering of plantations and other assets became so common that the whole country was brought to its knees. Firestone, owned by Japan’s Bridgestone, was occupied by rebels several times during the war that ended in 2003.

The company abandoned its operations during the conflict. Its research station, hospital, schools and other infrastructure were looted and destroyed. Millions of trees were “slaughter-tapped,” which means the tapping was so crudely done that trees died.

The company revived its operations, but the lawlessness did not end with the war. Illicit tapping is part of a wave of criminality driven by an 80% poverty rate and high unemployment, particularly among ex-combatants. Liberia’s police force, in the process of being restructured and professionalized, cannot cope with the crime wave.

Rubber is Liberia’s biggest export and the Firestone plantation, which is on 200 square miles, is the country’s biggest employer, with 6,000 workers. It exports concentrated latex and dried crumb rubber from Liberia.

Although the country is not a huge component of Firestone’s global operation, Liberia’s inability to protect its largest foreign investor in the war’s aftermath sends an alarming signal to other potential investors who are desperately needed to help provide jobs that the fledgling government cannot afford to create.

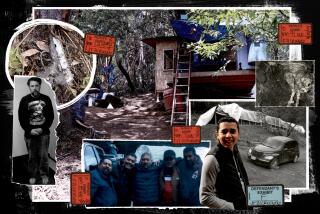

At Firestone’s compound outside Liberia, charcoal smoke drifts over vast tracts where once-healthy trees that could have lived 30 years have been felled and uprooted by the illicit tappers.

The destruction stretches as far as the eye can see. In other areas, seedlings about a foot high stretch to the horizon, part of the company’s project to replant as many as 5,000 trees a year.

But the trees will take seven years to mature. Meanwhile, more trees are being killed by the thieves.

It is not just Firestone that is suffering the aftereffects of war. A United Nations report last year said former combatants controlled several rubber plantations in Liberia, where gangs or private security guards often arrested people illegally. Working conditions across all plantations have declined, the government says.

Firestone says it has started rebuilding schools, housing and hospitals and that it plans to invest $100 million to upgrade the plantation and facilities.

A group of human rights activists filed a lawsuit in California against the company, claiming conditions were akin to slavery. A Firestone spokesman in Liberia, Rufus Karmorh, said the company would vigorously contest the action.

“The damage caused since 1990 has been enormous. Firestone was not on a different planet during the war. We were right here,” Karmorh said.

Joseph Kolli, a tapper, works from about 6 a.m. to 2 p.m., covering as many as 600 trees a day. Rubber tappers use a curved blade to shave off the bark of rubber trees, millimeter by millimeter. The drops of latex build into a rivulet, which drips into a metal spout. Tappers can carry two buckets filled with as much as 125 pounds of latex. They are paid $3.38 a day for their work.

“It’s tough work. The tapping ... requires concentration. You have to observe the tree, because cutting the tree can make the tree die,” said Kolli, who added that he and his co-workers fear the bandits. “They have been throwing acid on people. People are afraid of going to work because these people are wicked.”

Unprocessed, the latex is 30% rubber. After collecting the latex, ammonia is added to prevent coagulation and it is sent to a centrifuge in Harbel, 32 miles from Monrovia, the capital, where the concentration process takes place, turning the liquid into 60% rubber. It is then exported as latex concentrate. Other latex and rubber is processed, dried and baled for export.

Aside from political pressure to improve working conditions, Firestone’s biggest problem in recent months is the gangs of illicit tappers: Several staff members have been killed or survived murder attempts. Sometimes, the rubber pirates come in bands of 40 or 50 people.

Brown, the security guard, was in his office in February last year when a gang of several dozen men and teenage boys surrounded the building. They held an oil tapper, Joseph Taylor, whom they had stripped, beaten and taken hostage.

“I ran outside,” Brown said. “They said they came because we [Firestone’s security force] always tried to stop them tapping. They said Firestone is elephant meat, so we have no right to stop them.

“One of them rushed up and wanted to chop me with a cutlass, but I hit him with my fist and decided to run,” he said. “I slipped on a pipe and fell. When I fell they [splashed] the acid all over my ear and my body. It burned like fire,” said Brown. “Up to now I still feel pain.”

In an office at Firestone’s headquarters in Liberia is a notice board with horrifying photographs of several men killed with machetes or acid. Many others have been maimed.

“The atmosphere on the farm is very bad because you can’t move freely because of these guys,” Brown said.

The attacks have left many rubber tappers terrified. The members of Firestone’s security force who have been most affected by the attacks are shaken -- and angry that they can’t protect themselves with pistols as they did before the war. Since militias were disarmed, private security forces are not permitted to carry guns.

Some police have been dispatched to help protect Firestone workers, but they too are unarmed. Liberian police have had no weapons for three years, and the first shipment of pistols to arm some police was donated by Nigeria in late November.

Brown said the security force was impotent without guns.

“They want to be armed,” he said. “That’s the only way the criminals will be afraid and stop what they’re doing.”

Karmorh said it was the government’s responsibility to provide a secure environment for investors, warning that illicit tapping was threatening Firestone’s recovery efforts.

“The illicit tappers shorten the lives of the trees, and without trees there will be no Firestone,” he said.

*

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.