Turning his attention to race

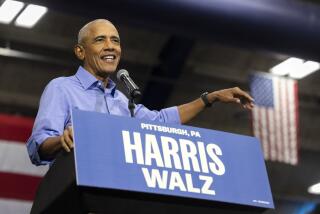

ORANGEBURG, S.C — . -- Barack Obama was down to his shirt-sleeves under the hot gym lights at South Carolina State University, exhorting students at this historically black college that America can and must be transformed.

“We cannot treat our poor with disregard,” he thundered Tuesday, cataloging America’s racial ills, starting with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. “We can’t leave New Orleans in a mess and then expect to be a model for this world.”

Here at the site of the Orangeburg Massacre -- where three students were killed and 27 injured by law enforcement agents during civil rights-era demonstrations to integrate a nearby bowling alley -- Obama decried a criminal-justice system fraught with inequity.

“I don’t want Scooter Libby justice for some and Jena justice for other folks,” he said, contrasting the white Republican ex-lobbyist with the black youths in Louisiana.

It could be the calendar, the electoral map or the recent flap between the Democratic front-runners. But the senator from Illinois is being forced on the campaign trail to address America’s racial inequities more directly and more often than before.

Obama has based his political career on campaigning beyond race, “trying to tap into the fact that a lot of Americans can deal with African Americans as long as they don’t talk about race,” said Susan Carroll, senior fellow at the Rutgers University Center for American Women and Politics in New Jersey. “It’s an incredible balancing act.”

In the initial phase of the 2008 campaign, Obama was largely able to finesse the difficult feat of appealing to white voters without alienating African Americans by framing traditionally racial issues in broader socioeconomic terms that allowed listeners from widely divergent backgrounds to hear what they wanted.

And many of the black electorate’s early concerns that Obama could not be elected because of his race were assuaged by his win in Iowa, one of the whitest states in the country.

But the race for the Democratic presidential nomination just wended its way through ethnically diverse Nevada and landed in South Carolina -- home to one of the largest concentrations of black voters in the country, as well as Saturday’s important primary.

Obama got here just in time for the holiday commemorating the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday and the Congressional Black Caucus Institute debate, where he cast his usual message of colorblind unity in distinctly racial terms, arguing that “white, black, Latino, Asian people want to move beyond our divisions.”

En route, he directly addressed black skepticism about his candidacy, telling an audience gathered to remember the slain civil rights leader that “sometimes it takes other folks before we believe in ourselves. Sometimes we’ve got that thing in our heads that says we cannot do something. . . . I’m here to tell you it’s possible.”

So far, the young are signing on. But a generational divide still exists between those whom Obama courts on college campuses and older blacks who lived through blatant segregation and the civil rights movement.

At a town-hall meeting Wednesday in Rock Hill, S.C., Rita Johnson, a 45-year-old laboratory technician, asked Obama how she could convince her 77-year-old father, an African American former security guard, that Obama could be effective in the White House.

Obama’s response was long and forceful. Blacks and whites together elected him to the U.S. Senate, he said, and Americans care more about what elected officials can do for them than the color of their skin. He ended with a warning.

The barriers are “inside our own heads,” Obama said to the largely black audience. “I don’t want to perpetuate this notion in our kids that there are limits to their dreams. . . . Tell your father that he’s got to be making sure he’s not passing on that mind-set to his grandchildren.”

Obama’s current campaign style is in stark contrast to his style in Iowa and New Hampshire, where his racial references were unusual and oblique.

Unlike Hillary Rodham Clinton -- who often mentions that older women tell her they want to help put one of their own in the White House -- Obama did not talk about the historic nature of his own run.

He’d say his mother was from Kansas and his father from Kenya, but he would never mention that one was white, the other black. He’d explain that his youthful White House run was fueled by “Dr. King’s fierce urgency of now,” without elaborating.

He answered a question about federal drug-sentencing guidelines without saying the word “black,” though activists have long complained that stiffer sentences are meted out to blacks who smoke crack than whites who snort cocaine.

He’d acknowledge that he talked a lot about hope, then credit his upbringing and leave it at that -- single mom, little money, no privilege. Once in a while, he’d add a jolting teaser, which underscored how rarely he spoke about race at all.

“I mean, think,” he exhorted supporters at the Catfish Bend Casino in Burlington, Iowa. “You’ve got a black guy named Barack Obama running for president. You’ve got to have hope.”

Chief campaign strategist David Axelrod said that Obama was proud of his heritage and understood “the historic parameters of his quest” -- but that he didn’t need to belabor it to attract African American voters.

For the most part, Obama has been able to hew to his central message without belaboring race because he is what Todd Shaw, a professor of political science and African American studies at the University of South Carolina, calls a “second-paragraph” candidate.

“He anticipates in an interesting way what the audience is thinking and starts with the second paragraph,” Shaw said. What is implied in his oratory, Shaw said, is: “I know that you see me as African American. Now that we have that out of the way, here’s why you should vote for me.”

Shaw also argues that Obama’s indirect references to the civil rights movement or racial and economic disparities function as a kind of universal code that is interpreted differently depending on the listener.

“He lets his audience hear what they want to hear,” Shaw said. “He knows that the same thing in different audiences strikes a slightly different chord, and that’s OK. . . . You see what you want to see.”

But South Carolina has excised Obama’s campaign-trail luxury of self-definition as a multicultural candidate in a colorblind world. The Feb. 5 contests in 22 vastly disparate states present a far more complex challenge. And a more diverse audience is beginning to pay attention.

Research by Michael Dawson, founder of the Center for the Study of Race, Politics and Culture at the University of Chicago, outlines the hurdles facing Obama.

In a national survey on racial attitudes in America after Hurricane Katrina, nearly 80% of black respondents said this country would not achieve racial equality in their lifetimes -- if ever. In contrast, two-thirds of whites said the goal had already been accomplished.

Although recent polls indicate that Americans are increasingly comfortable with the idea of a black president, the best way to win their votes is to “focus on his vision for the country above and beyond race,” said Danielle Vinson, professor of political science at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. “If Obama were to become the candidate of race, he’ll be more limited about who he can attract.”

--

Times staff writer Seema Mehta contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.