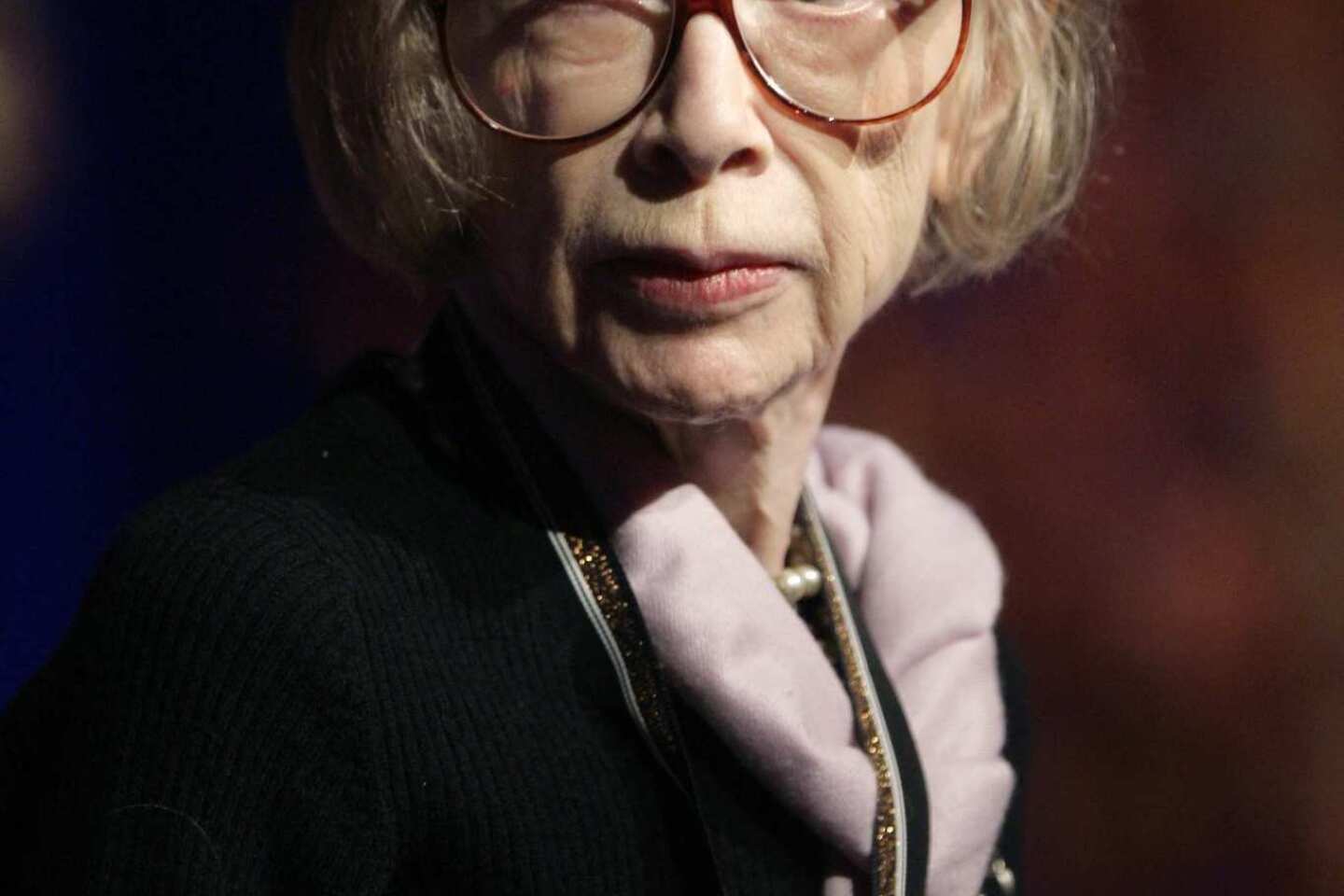

‘The Year of Magical Thinking’ by Joan Didion

The back cover of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Joan Didion’s first collection of essays and the book that established her as one of a handful of major contemporary writers, advises that her pieces “all reflect, in one way or another, the notion that things are falling apart, that ‘the center cannot hold.’ ” That phrase is from Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” the poem that provided Didion with the 1968 book’s evocative title; such slouching perhaps now is more firmly associated with Didion than with Yeats. To say that those essays as well as her subsequent works also reflect the notion that things are falling apart is a literary allusion that many will recognize; in most ways, it is perfectly true.

It is also perfectly trivial. What Didion does is something more difficult and enduring. Although she has an acute sense of historical decay -- of the discontinuities that estranged the Haight-Ashbury generation from their parents’ universe, of the focus-group politics that have estranged us from Washington -- her writing encompasses far more than stories of contemporary decline. Despite our nostalgic illusions -- of the sort she dissolved in her 2003 book on California, “Where I Was From” -- no center has ever held. Her pieces examine how lives do and do not withstand such disintegration.

In her new book, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” the life that persists amid the disorder is Didion’s, and the salient tatter of poetry that inspires her is from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” The lines that now reverberate in her inner ear are Eliot’s: “these fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

On Christmas Day 2003, her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne Michael, was admitted to the intensive care unit at Manhattan’s Beth Israel North hospital after a bout of flu became pneumonia and then septic shock; a coma was induced and Michael was placed on life support. Five days later, after Didion returned home from a hospital visit, her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, collapsed at the dinner table with a fatal coronary.

By the end of January 2004, her daughter’s condition had improved; a memorial service was held for Dunne, and Michael made plans to recuperate in Los Angeles with her husband. But when Michael arrived at LAX, she fainted and later underwent six hours of neurosurgery to relieve a hematoma. “The Year of Magical Thinking” is an aching -- and achingly beautiful -- chronicle of this year of fragments shored against Didion’s ruins.

When she writes of “magical thinking” -- or “delusionary thinking, the omnipotent variety,” or “the way children think” -- she’s not speaking figuratively. It’s as if her “thoughts or wishes had the power to reverse the narrative, to change the outcome.” As if her magical thinking would fix the world that has fallen apart. The book moves in and out of scenes, across 40 years of marriage and one year of disarray; it is littered with halting, half-connected lengths of narrative. In one scene, Didion cleans out Dunne’s closets, bags his T-shirts, shorts and socks and drops them off at the church across the street. She goes to his office with garbage bags for the clothing there. She is arrested by a thought:

“I could not give away the rest of his shoes.

“I stood there for a moment, then realized why: he would need shoes if he was to return.

“The recognition of this thought by no means eradicated the thought.

“I have still not tried to determine (say, by giving away the shoes) if the thought has lost its power.”

Many such wishful episodes revolve around how Didion uses language to try to preserve order and continuity. For as long as she can remember, she explains, “meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs.” Now the words she hears and repeats are no longer just words but magical words, charm words. She steeps herself in the literature of grief: C.S. Lewis’ “A Grief Observed,” his diary of the year after his wife’s death; psychoanalytic essays on mourning by Sigmund Freud and Melanie Klein; clinical papers by psychiatrists on the differences between “normal” and “pathological” bereavement.

Her research on her daughter’s condition is even more thorough and aggressive as Michael recovers in a rehab unit. (Michael passed away in August, after this book was completed.) Didion reads neurology textbooks, inhabits a surgically precise idiom like an A student at medical school, snaps commands and reminders at doctors and orderlies, looks to these potent words and slabs of information as bulwarks against the dilating pain of helplessness and loss.

They are, after all, inquests Didion has made before: These lean, unsparing descriptions of her fragmentary responses are all the more powerful because the writer has spent her career outlining the magical postures of others. Again and again, she has been drawn to all varieties of what she once called “protective talismans, totems, garlands of garlic, repeated pieties.” In that case, she was referring to the state of political discourse after Sept. 11. “The presence of rain at a memorial for fallen firefighters,” she noted in the New York Review of Books in 2003, “was gravely reported as evidence that ‘even the sky cried.’ ” In her year of magical thinking, such omens overcrowd her own life. She blots out portions of reality by connecting too many dots.

In the title essay of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” about San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury in the cold spring of 1967, Didion suggested that because that generation did “not believe in words ... their only proficient vocabulary [was] in the society’s platitudes.” Now she admits to her own intermittent aphasia, to a wild linguistic ambivalence that runs between her limitless faith in the power of words and the suspicion that she no longer has a single useful word at her disposal.

Didion reviewed the “Left Behind” series by Tim LaHaye, Jerry B. Jenkins and others -- the eschatological thrillers that sell by the millions to evangelical Christians -- in 2003. Their rapture-bound heroes are unshakably competent: They fly airplanes, hack computers, improvise arsenals. “In many ways,” she wrote, “it is from this assumption of confidence, of the ability to manage a hostile environment, that the series derives both its potency and its interest” for readers who feel overwhelmed, often by economic disadvantages. In “The Year of Magical Thinking,” she writes of her helpful professional friends who “believed absolutely in their own management skills. They believed absolutely in the power of the telephone numbers they had at their fingertips” and realizes that “I had for most of my life shared the same core belief in my ability to control events.”

We have come to admire and love Didion for her preternatural poise, unrivaled eye for absurdity and Orwellian distaste for cant. It is thus a difficult, moving and extraordinarily poignant experience to watch her direct such scrutiny inward. She has mentioned her instability with some frequency -- most notably in the title essay of “The White Album” (1979) -- but she’s never before revealed the sort of purblind drift in which this book is steeped. She has cast herself as anxious but mostly reasonable: “an attack of vertigo and nausea,” she once wrote, “does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.”

The difference between her own fragments shored against these unhappy ruins and those fragments -- fanciful wishes and narrow half-truths and gaudy amulets -- marshaled by her previous subjects is this: We are left with the impression that her near-pathological honesty will in time allow her to cope -- without magic -- with things falling apart. Didion has helped us understand and anticipate how magical thinking and its attendant self-deception have caused -- and will continue to cause -- political train wrecks, social dislocations, despair. “I have as much trouble as the next person with illusion and reality,” she once confessed. Unlike most of us and most of her subjects, she has brought herself to admit it in a manner that is as artful as it is honest.

Her admissions are severe and often excruciating. They also are as instructive, resonant and searing as her 40 years of sympathetic stories about how we deny our trouble discerning illusion from reality, how we pretend that things aren’t falling apart.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.