Column: Is California’s move to a $15 minimum wage a good idea? Here are the facts.

- Share via

California is poised to launch a great experiment in practical economics by raising the statewide minimum wage to $15 an hour through 2022.

The proposal, hammered out over the weekend by Gov. Jerry Brown and labor organizations, would raise the rate from $10 an hour to $10.50 on Jan. 1, 2017, with a 50-cent increase in 2018, further $1-per-year increases through 2022, and inflation-indexed increases after that. Businesses with fewer than 26 employees would have until 2023 to hit $15.

The deal still must be approved by the Legislature, and the battle there may be bruising, with stiff opposition coming from business ownership groups; indeed, the unions' desire to avoid a costly battle over a proposed ballot measure raising the minimum wage motivated the negotiations.

Lifting the minimum wage to $15 an hour would not just be quantitatively larger than previous U.S. experience, but qualitatively different.

— Adam Ozimek, Moody's Analytics

Two factors make California's plan such a pioneering step: the size of the increase and the size of the state. About 600,000 of California's 1.6 million manufacturing workers earn less than $15 an hour today, estimates Adam Ozimek of Moody's Analytics. That's by far the largest block of affected manufacturing workers, and it's potentially a key metric because it points to how the size of California's proposed increase reaches out to different employment sectors than a smaller increase would.

"Lifting the minimum wage to $15 an hour would not just be quantitatively larger than previous U.S. experience, but qualitatively different," Ozimek observed in September. Leisure and hospitality workers -- those most commonly thought to occupy the lowest rung of income -- "make up 54% of the workers who make less than $8 an hour, but only 34% of those making less than $15 an hour." Critics of the plan are sure to use these figures as an indication of which jobs are most threatened by the $15 minimum.

First out of the box with an opposition manifesto Monday was the California chapter of the National Federation of Independent Business, which styles itself "the voice of small business" but actually is associated with big restaurant franchisers and organizations connected with the Koch brothers. The group has been in the forefront of opposition to paid family leave and the Affordable Care Act; its lawsuit to overturn Obamacare led to the landmark 2012 Supreme Court ruling upholding the law. The NFIB called the California deal "reckless" and observed, that "small businesses in California are still struggling to cope with the 25% minimum wage hike over just the past two years." This is a huge exaggeration: California's minimum wage increased to $10 this year after being raised to $9 on July 1, 2014, and to $8 on Jan. 1, 2008; the proper math would place the increase at 25% over eight years, or 11.1% over the last year and a half.

That still leaves the question of whether the increase to $15 is warranted. Let's break it down.

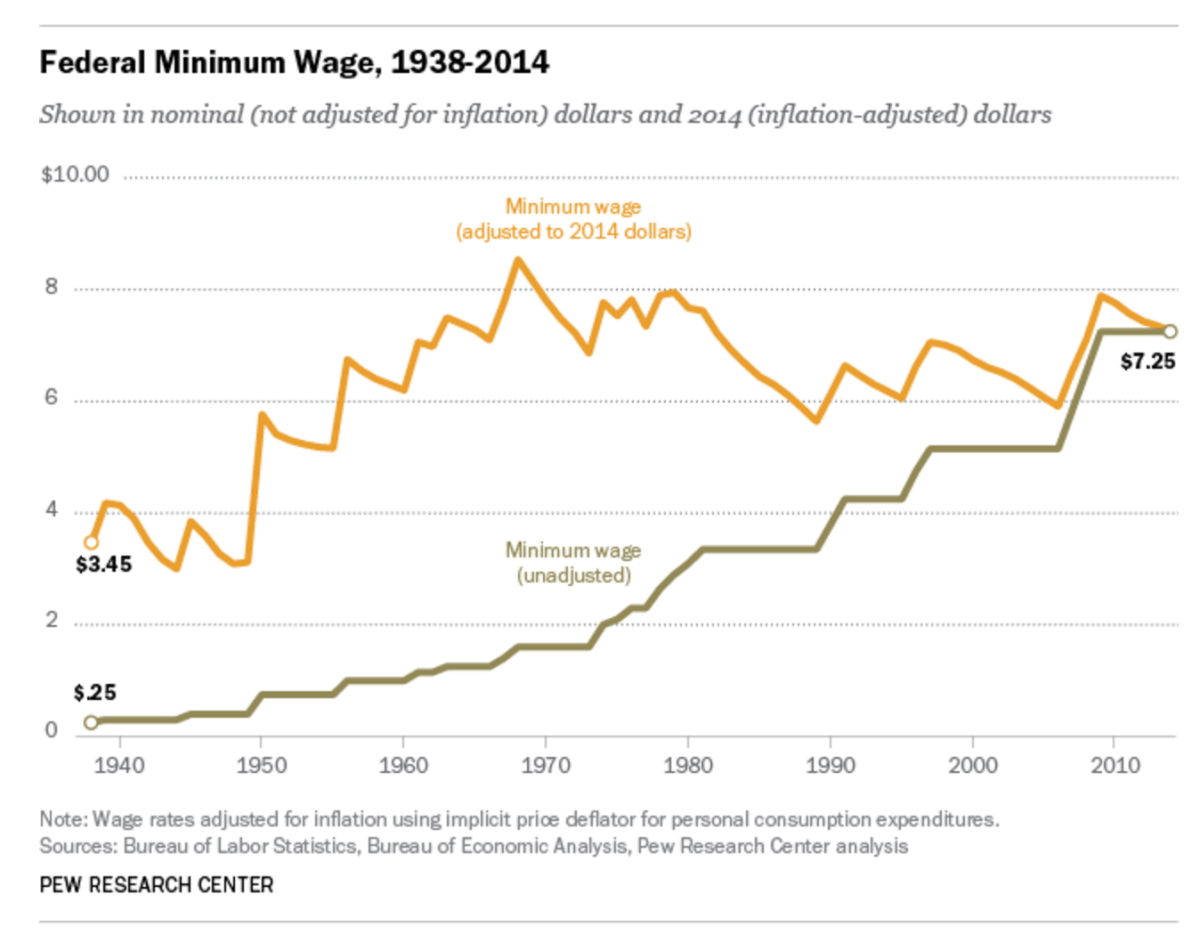

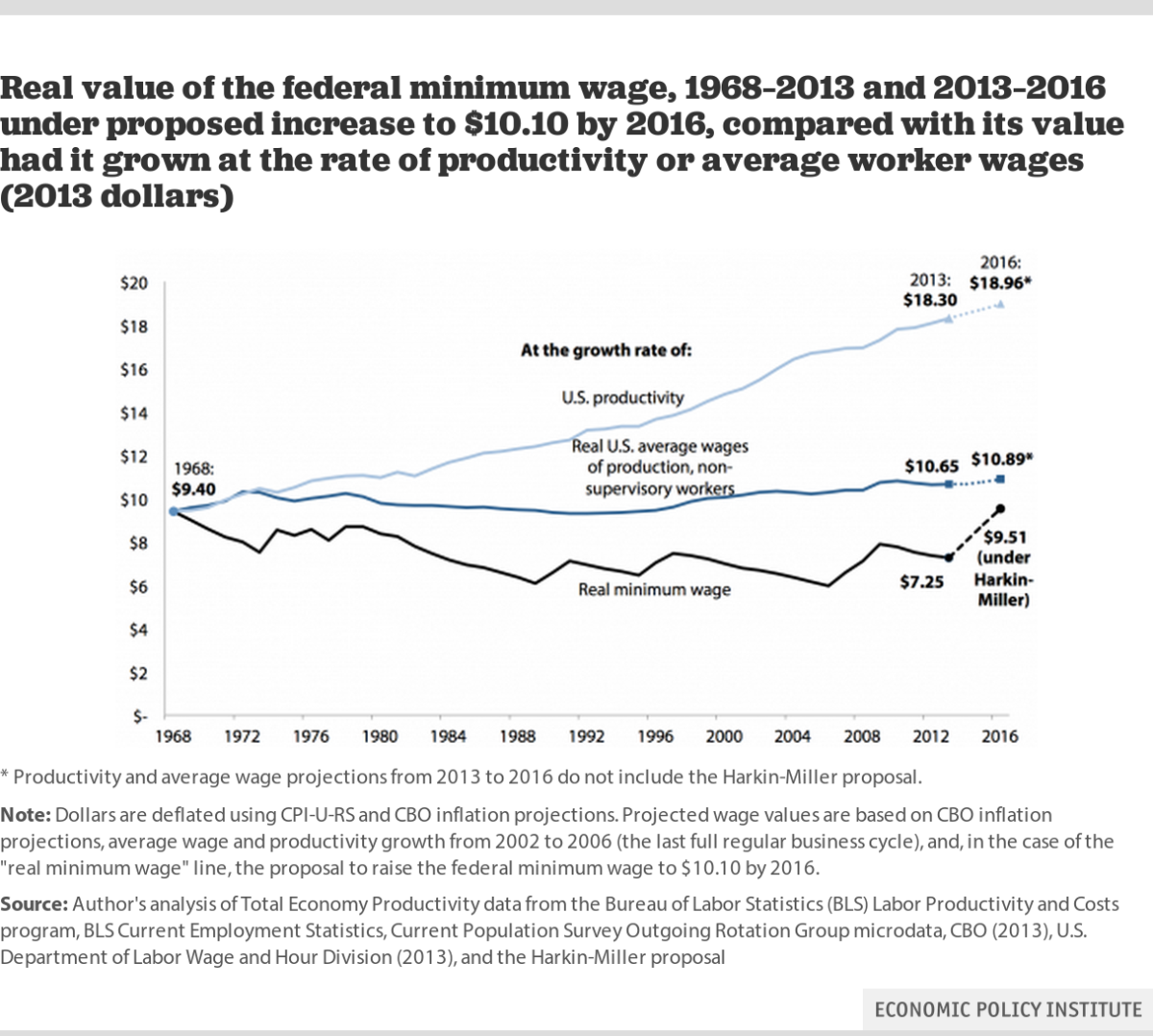

The most important rationale for increasing the minimum wage is that it has fallen in value since reaching a peak, in inflation-adjusted terms, in 1968. The federal minimum wage of $1.60 that year would be worth $10.90 now, far more than today's federal minimum of $7.25. That provides some context to proposals from the Obama White House and congressional Democrats to raise the federal minimum to anywhere from $10.10 to $12 an hour through the end of this decade. (The federal minimum wage governs only in the 21 states that haven't set higher minimums by state law.) Inflation obviously will continue to eat away at the minimum wage; if the low-inflation levels of the last six years continue through the next six, California's proposed $15 minimum in 2022 would be worth only about $13.79 in today's buying power.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

Those proposals also would leave the federal minimum wage well below the level it would have reached if it tracked increases in U.S. productivity or real average wages for rank-and-file workers, according to the Economic Policy Institute, which is associated with labor organizations and other progressive groups. That's important -- productivity gains drive economic growth and the overall standard of living; the disconnection between average hourly compensation and productivity, which began in the early 1970s, is widely considered to be an underlying cause of increasing economic inequality in the U.S. While income generally has flowed away from labor and toward shareholders during this period, minimum wage workers fall further behind.

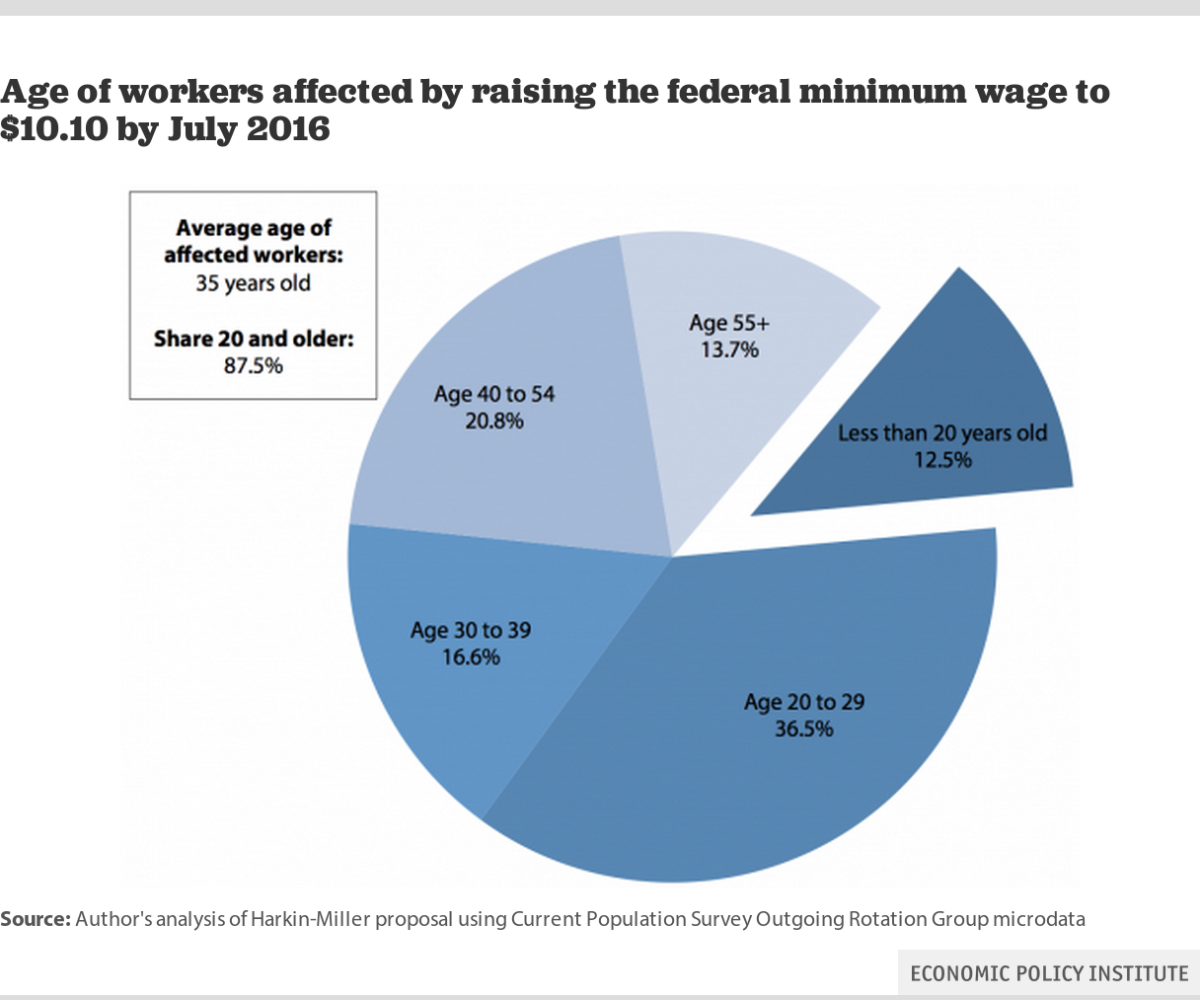

That brings us to the question of who constitutes the minimum-wage-earning class. Here's where myth and reality about the minimum wage come into stark contrast. The popular image of the minimum wage employee is a teenager flipping burgers or tending a fast-food counter as stop-gap employment to bigger and better things, whether college or a career path. Increasingly, that's not so.

The minimum-wage culture has risen in age, widened in terms of educational attainment, and spread to occupations well beyond fast food. Minimum wage workers today comprise hotel housekeepers and home healthcare workers

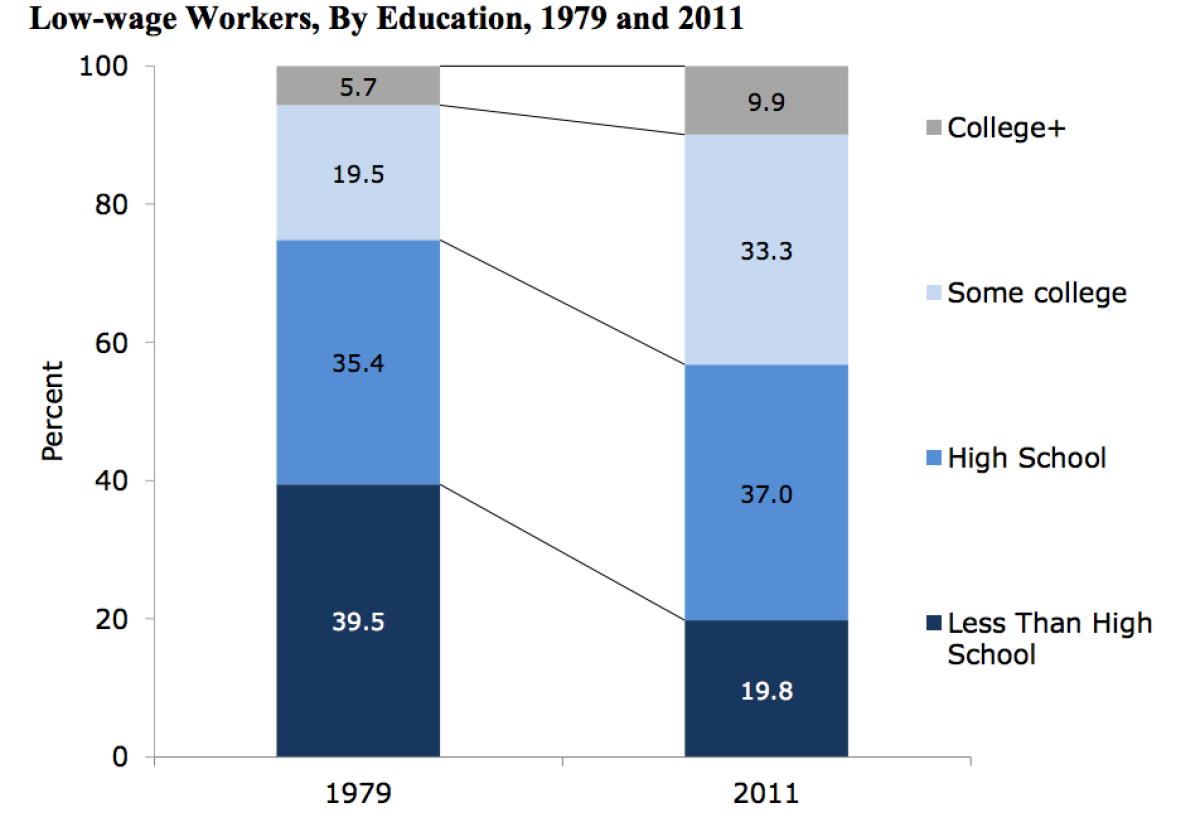

Only about 12.5% are those proverbial teenagers; in fact, more than a third are aged 30-54, which are family-raising years, signifying that a substantial number are engaged in long-term employment. Over the last three decades, according to a survey by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the share of all low-wage workers who have attended or graduated from college has risen to 43.2% (in 2011) from 25.2% (as of 1979). The share of those without a high school diploma shrank to less than 20% from nearly 40% in that time frame.

For many workers, the minimum wage has become less of a transitional phase than ever. As Ben Casselman of fivethirtyeight.com reported last year, in the mid-1990s "only 1 in 5 minimum-wage workers was still earning minimum wage a year later. Today, that number is nearly 1 in 3" This implies that many employers have become hooked on the minimum wage: why give workers a raise, as long as they have no bargaining power? That's a reflection both of continuing slack in the labor market and the decline of unions in the private sector.

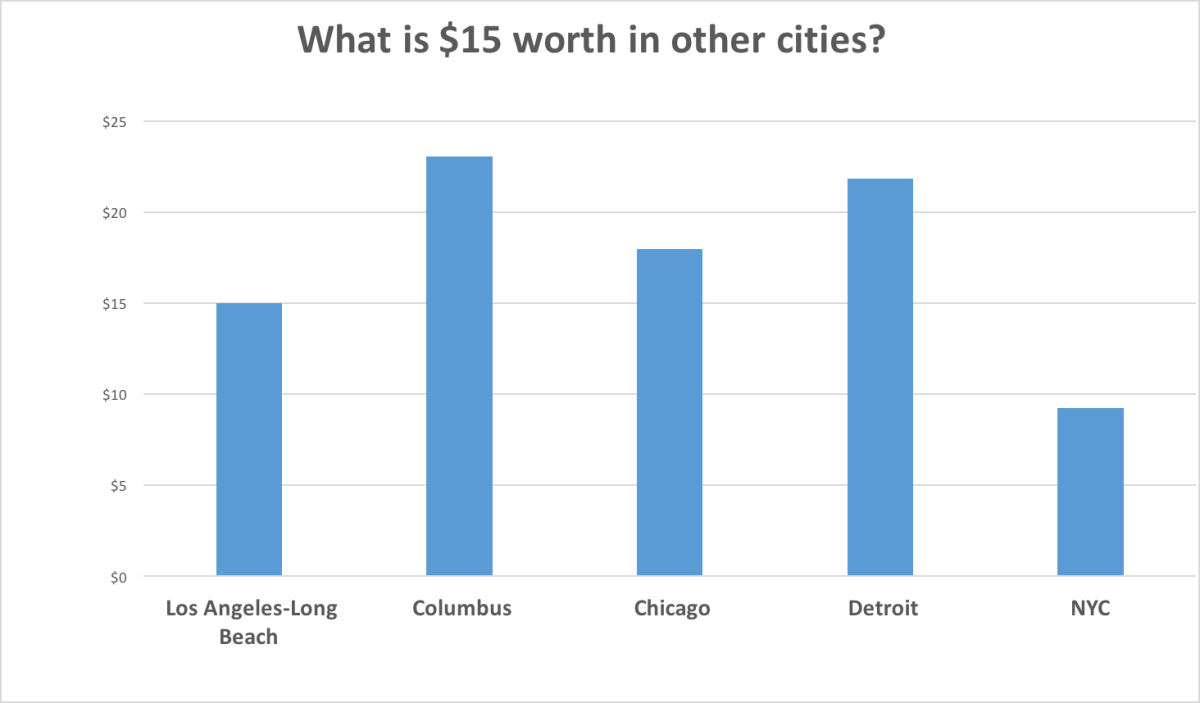

One other important factor in judging whether a $15 minimum wage is justified is how it corresponds to the cost of living. This is key, because $15 an hour can fund a relatively comfortable existence (though obviously not a lavish one) in some places while keeping its earners at or even below the poverty line in others. As I reported last year, after the Los Angeles City Council raised the minimum wage to $15 by 2020, the cost of living in L.A. is about 40% higher than the U.S. average, according to figures from the Council for Community and Economic Research. As fivethirtyeight's Casselman calculated, the nation's best city for minimum wage employees was Columbus, Ohio, where the statutory minimum of $8.10 is worth $8.91, adjusted to the national average cost of living.

In terms of local buying power, $15 doesn't go nearly as far in L.A. than in Columbus (where it's worth $23.03, according to the CCER's figures), Chicago ($17.96) or Detroit ($21.83), though it goes further than in Manhattan (a mere $9.24). This complicates judgments about whether a $15 minimum wage is "too high." Relative to what?

All these considerations still leave us with the issue of what the minimum wage should be -- or more specifically, what are the chances that a raise to $15 through 2022 will provoke an exodus of jobs from California.

For decades, economists have searched for signs that higher minimum wages cost jobs, largely without success. Even studies that have forecast job losses find that those are minimal compared with the gains in income to the minimum wage class overall, and especially to low-wage workers generally, whose pay is likely to be pushed up as the minimum rises. Perhaps the most notable such studies came from the Congressional Budget Office, which examined the likely effects of an increase in the federal minimum to $10.10 by 2020.

That option would lead to the loss of 500,000 jobs, the CBO projected (within a range of zero to 1 million workers). But vastly more, 16.5 million workers, including those earning just above the minimum, would end up with higher pay. About 900,000 people would move above the poverty line. Families whose income was below the poverty line would gain a total of $5 billion, those with income up to three times the poverty threshold would gain $12 billion. Overall income in the real economy would expand by a net $2 billion. Would this be a good deal? It depends on whether you focus on the 500,000 potential losers or the 16.5 million gainers.

What's important about this study and many more like it is that they don't measure the impact of an increase on the scale California is contemplating. This is a fair point, and underscores that the state's initiative, if it happens, would be very much an experiment. If it goes wrong, as some commentators have observed, the victims are likely to be the poorest of the poor, many of whom already are out of the reach of any economic safety net as it is. If it goes right, however, California could establish a redefinition of "low income" that begins to redress the long imbalance of economic power in the U.S. Income would flow, incrementally, from business owners and customers toward the people who perform the most menial and unrewarding work in the economy. Is that a bad thing?

The powers that be have been performing experiments on the U.S. economy for several decades now. For example, there was the experiment in tax-cutting for the wealthy that began with the Reagan-era "trickle-down" theory and the Laffer Curve. There was the experiment in debt-funded military adventurism launched by the George W. Bush administration. There are the experiments in privatization of public services that have swept state legislatures coast to coast.

These experiments have proved to be disastrous for huge groups of Americans, especially the middle class. They've suppressed economic growth. They've saddled us with enormous debts that are being laid on the shoulders of the neediest, including Social Security and Medicare recipients. They've led to the impoverishment of public universities, soaring college tuition and mushrooming student debts.

Most of all, they've led to the very phenomenon of stagnant wages for the middle and working classes that the campaigns for higher minimum wages seek to address. Those experiments have failed, but maybe it's time to try one that starts at the bottom of the income ladder and seeks to find if gains there will trickle up.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com

Return to Michael Hiltzik's blog.

ALSO

Op-Ed: A minimum wage hike is the wrong fix

Will the $15 minimum wage pass California's Legislature? And other key questions...

News of a minimum wage hike deal in California is met with relief -- and anxious arithmetic

UPDATES:

3:54 p.m.: This post has been updated with a correction from Gov. Brown's office stating that the one-year delay in the $15 minimum wage applies to small businesses with fewer than 26 employees, not 25.