Why do we pay so much for lousy investment advice?

- Share via

The unspoken subtext of the Obama administration's recent initiative on brokers' responsibilities to their clients was that individual investors are vulnerable to being ripped off by the financial services industry. (I wrote about the new broker rules here.)

But the new rules didn't lay a finger on one of the most important ripoff tools of the financial services industry: high fees for managing money.

Economists Brad DeLong, James Kwak, and Noah Smith have all weighed in on the question of why Americans pay so much for advice that typically turns out to be nearly worthless. The discussion was launched by Kevin Drum of Mother Jones, who simply asked why monopoly rents were being collected by a finance industry so competitive that its profits should long ago have been "reduced to zero, or close to it."

We are paying a very heavy price indeed for having disrupted our ... oligopoly-ridden post-Great Depression New Deal financial system

— UC Berkeley economist Brad DeLong

He's right that the financial services industry collects fees so large one would conclude that it's adding real, unique value. Plainly it's not -- in fact, the industry is a value-subtractor, especially if one counts the threat to the economy posed by imprudent bankers and financiers.

UC Berkeley economist DeLong put it this way:

It used to be that we collectively paid Wall Street 1% per year of asset value – which was then some 3 years’ worth of GDP – to manage our investment and payments systems. Now we pay it more like 2% per year of asset value, which is now some 4 years’ worth of GDP.

Add the systemic risk produced by "cowboy finance," he wrote, and "we are paying a very heavy price indeed for having disrupted our peculiarly regulated and oligopoly-ridden post-Great Depression New Deal financial system."

----------

RELATED STORY:

Here's why the new rules protecting retirement savers are needed

----------

DeLong conjectured that customers don't comprehend the impact of fees: "At a behavioral finance level, people 'see' commissions but do not see either fees or price pressure effects."

Smith of Stony Brook University extended this idea by explaining why the cost of asset-management fees can be hard to understand. One reason is that people don't realize that, unlike commissions, they get collected every year.

"Wealth managers," as he calls them -- your brokers or financial advisors -- collect a percentage of your assets under their management, and off the top. If it's 1%, then of the $100,000 you've placed with the manager, only $99,000 is left to be invested.

This is easy to understand when it’s just one year. And $1,000 sounds pretty reasonable. But ... the fees add up. And it’s that part that I suspect investors are very bad at comprehending. Every year, the fee gets charged again. ...That $1,000 is only the slice in the first year. Whether your wealth grows or shrinks, another 1 percent slice is going to be lopped off of your entire net worth the next year. Slice, slice, slice. Those slices add up, big time.

How big? Smith calculates that for a portfolio matching the stock market's long-term return of about 7% annually above inflation, a 1% annual fee could erode a retirement portfolio by a total 25% compared to no fee. (That's for a family that places 6% of its income in the portfolio every year.)

Wealth managers aren't completely worthless, Smith acknowledges. They can keep clients from making bad investment decisions, or missing good opportunities. But too often, their pitch is that they can help clients beat the market. That happens so rarely and so inconsistently that claiming otherwise amounts to a scam.

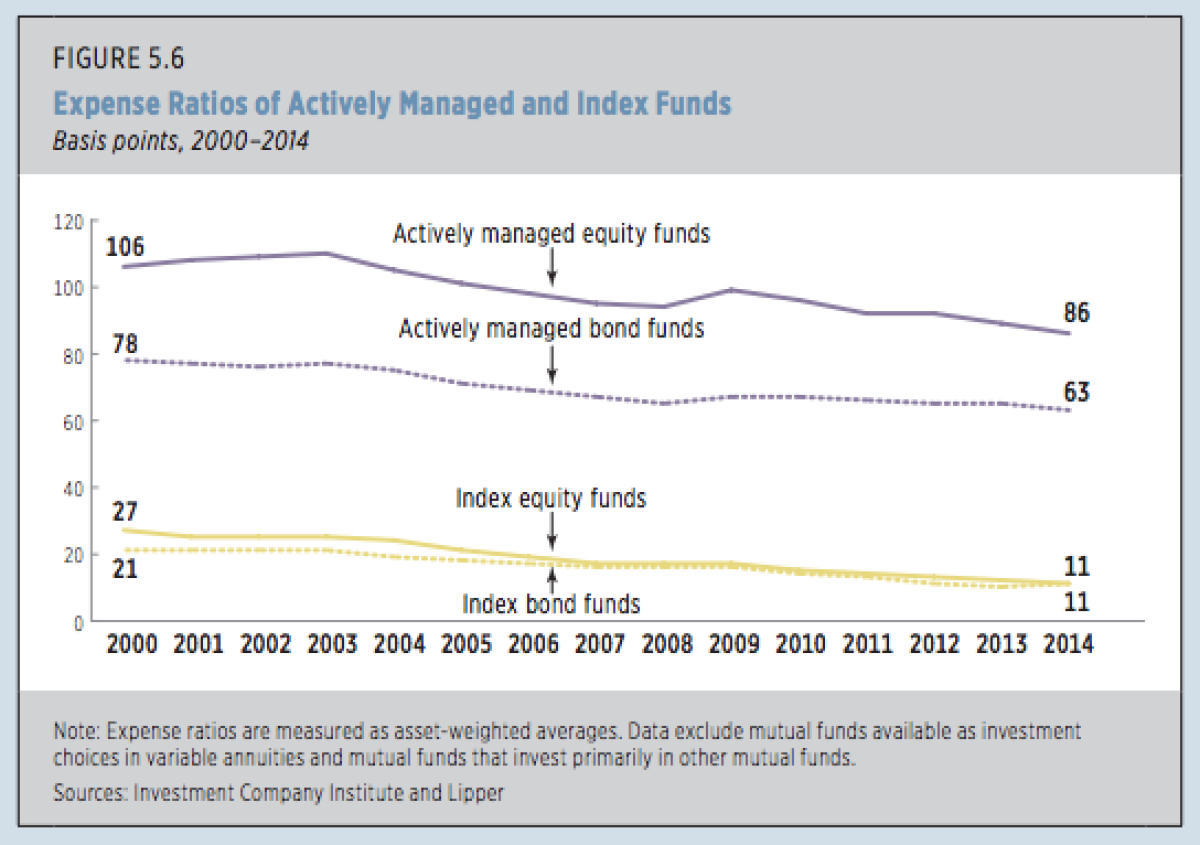

Kwak of the University of Connecticut Law School tugs on that thread. He observes that actively managed mutual funds carry an average expense ratio of 86 basis points (that's 0.86%), while passively managed index funds are down to 11 basis points.

Yet although index funds have enjoyed a vogue in recent years, they still account for "only about $2 trillion out of a total of $18 trillion in U.S. mutual funds and ETFs," he said.

Why do investors overpay so drastically for funds that consistently underperform the market? Kwak thinks it's because the higher fees are their own advertisement -- people believe there must be value in the premium price.

"This is a natural thing to believe," he wrote. "In most sectors of the economy, price does correlate with quality, albeit imperfectly. It’s also natural to believe that some people are just better than others at picking stocks, just like Stephen Curry is better than other people at playing basketball. ...This is one area where I think marketing does have a major impact, both in the form of ordinary advertising and in the form of the propaganda you get with your 401(k) plan."

To put it another way, the average investor can't be convinced that the outsized returns shown (termporarily) are due in part to taking on more risk and to "dumb luck."

You won't hear the investment industry talking much about that reality, except at Vanguard, where the business model is low-expense index funds. But it's worth remembering the most enduring joke about Wall Street. It's the one about the broker showing a friend around the marina where he and his partners dock their luxury sailboats.

"Very nice," says the friend. "But where are the customers' yachts?"

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.