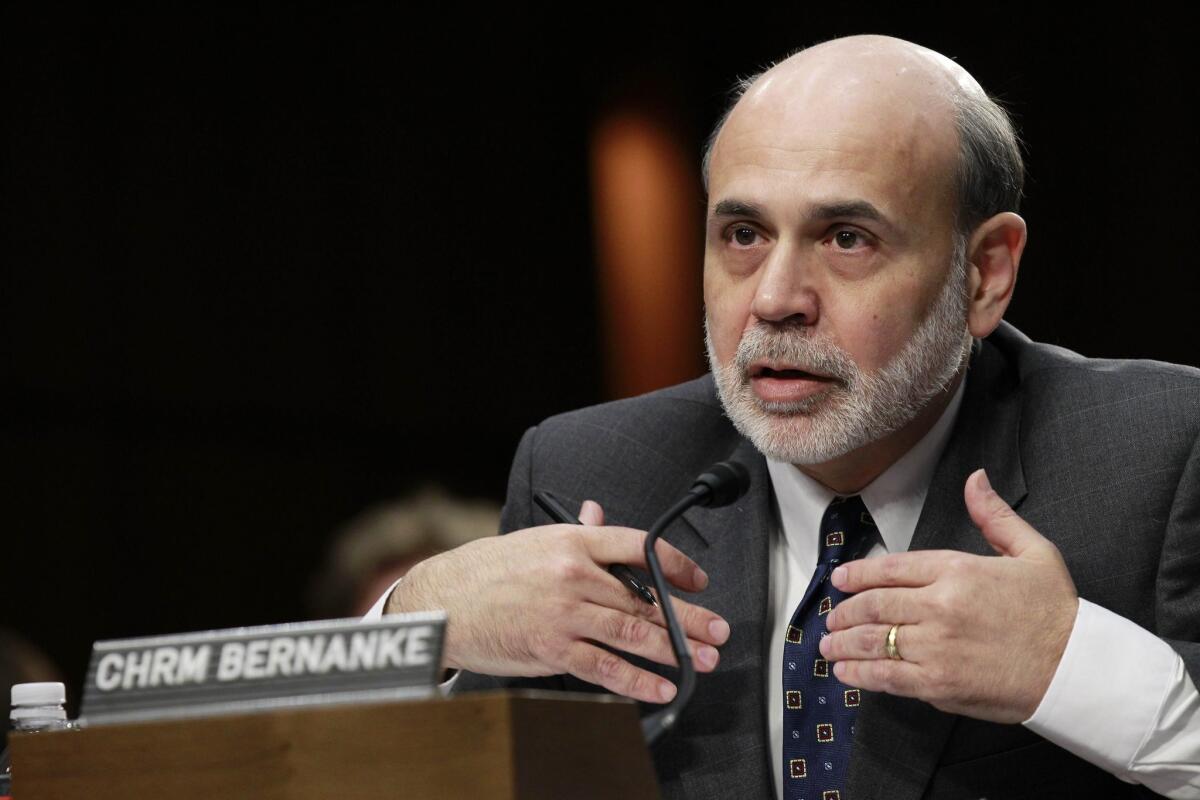

Column: Did Ben Bernanke really want to put bankers in jail? His new book says no.

Ben Bernanke testifies on Capitol Hill in 2012, when he was still chairman of the Federal Reserve.

- Share via

In an interview published in connection with Monday’s release of his memoirs, former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke casts his vote--retrospectively--for the prosecution of bankers and executives responsible for the recent financial meltdown.

Although this wasn’t within the Fed’s jurisdiction, he told USA Today that “it would have been my preference to have more investigation of individual action, since obviously everything what went wrong or was illegal was done by some individual, not by an abstract firm.”

He further questioned the policy of the Department of Justice to train its criminal investigations on financial firms, not the human beings who led them: “A lot of their efforts have been to indict or threaten to indict financial firms. Now a financial firm is of course a legal fiction; it’s not a person. You can’t put a financial firm in jail.... Obviously illegal acts ultimately are done by individuals, not by legal fictions.”

Everything what went wrong or was illegal was done by some individual, not by an abstract firm.

— Ben Bernanke, in USA Today

What’s curious about this discussion is that it doesn’t appear in Bernanke’s book, “The Courage to Act,” at least not in such strong terms. There’s no evidence in the text that Bernanke ever urged this policy on federal prosecutors during or after the crisis. Rather, he seemed to regard threats against individuals as counterproductive or, at the very least, irrelevant to what he considered Job 1 in real time: Keeping the economy from falling into a depression.

That’s one takeaway from Bernanke’s book. Among the others is his opinion that many of the executives he had to deal with were scoundrels or fools, and his feeling that austerity policies imposed by conservative governments have hampered the worldwide recovery. More on that in a moment.

On the issue of punishing individual wrongdoers, Bernanke writes that some critics who urged punishment for bankers were “uninformed,” characterizing their viewpoint as “the economy will be just fine if a few Wall Streeters get their just deserts.” He says he and the Treasury secretaries he worked with, Henry Paulson followed by Timothy Geithner, all shared the view that the practical aspects of shoring up the economy were more important than the “political considerations” pointing toward punishment of individual wrongdoers.

“Tim, in particular, complained about the ‘Old Testament’ attitude of politicians who seemed more interested in inflicting punishment than in avoiding impending disaster,” Bernanke writes. “We were fine with bad actors getting their just deserts, but we believed it was better to postpone the verdict on blame and guilt until the fire was out. [I] avoided sweeping populist indictments of bankers, in part because I knew that there was plenty of blame to go around, including at the Fed and other regulatory agencies and in Congress.”

This is a telling approach, because it’s a more aggressive approach to white-collar crime by federal prosecutors that well might have instilled bankers and executives with a healthier commitment to risk-aversion, possibly averting the crisis. Such an approach following the disaster that Bernanke had to clean up might help deter them from fomenting the next disaster. But no top bankers have gone to jail, or even been hauled into court.

The view of experts on white collar crime is that prosecuting corporations or imposing even stiff corporate fines has no deterrent effect on their leadership. The executives don’t pay the money, and in many cases the companies themselves can minimize the financial hit by reserving against it over time or writing it off on their taxes. One federal judge with jurisdiction over Wall Street has consistently expressed his frustration with wrist-slaps of corporations while their executives go free.

Bernanke’s treatment of bankers and executives during the financial crisis is tactful, but largely negative. He describes Angelo Mozilo of subprime mortgage lender Countrywide Financial as “white-haired” and “unnaturally tanned,” which is accurate as far as it goes.

His opinion of Dick Fuld, the head of Lehman Bros., the investment bank whose collapse precipitated the crisis, is withering--though couched in judicious words. He implies that Fuld was obsessed about short sales of Lehman stock, taking every short transaction “like a personal affront.”

But he blames Lehman’s fall on Fuld’s aggressive expansion of the firm’s lending, which “had blown through the company’s established guidelines for controlling risk.... Fuld and his team seemed in denial about how badly their bets had gone wrong.”

Eventually, the government officials trying to pressure Fuld into putting Lehman on the block concluded that Fuld “didn’t have a realistic view of what his firm was worth.” The implication is that Fuld’s blindness to reality prevented an orderly sale of Lehman, which might have averted the worst of the crisis.

Bernanke is intensely critical of the austerity policies imposed by European governments after the crisis and, to a lesser extent, by Congress. This is unsurprising, since Bernanke throughout the crisis pleaded consistently for more expansionary government fiscal policies and, when they didn’t appear, took up the slack through an aggressively expansionary monetary policy from the Fed.

Among developed countries, he writes, “the United States has had the strongest recovery because the Fed eased monetary policy more aggressively than did other major central banks, and because U.S. fiscal policy, although a headwind during most of the recovery, was less restrictive than elsewhere.”

His targets include British Prime Minister David Cameron, whose tighter fiscal policies led to Britain’s inability to “perform quite as well” as the U.S. in recovery; German leaders and others in the Eurozone, who “pushed too hard and too soon for fiscal austerity” in countries that didn’t need it in the near term--indeed, needed just the opposite; and European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi, who finally implemented monetary easing, but not until 2015, six years late.

So Bernanke’s insights are instructive about what went wrong and how to keep it from happening again. But they might have been strengthened by a dose of the prescription he hinted at with USA Today: Punish the human beings who created the crisis.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.