Brands like HP and Apple try film to reach young consumers who skip commercials

- Share via

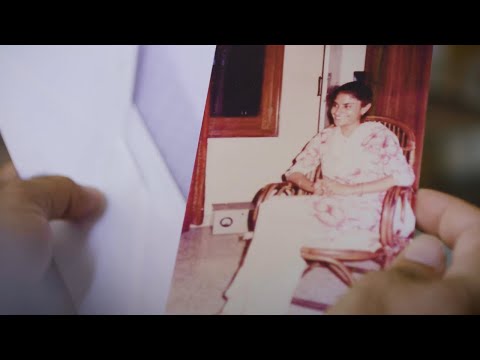

Reporting from San Francisco — Harbinder Singh was skeptical about arranged marriages, but when he received a photo of his potential wife-to-be, he was wowed. “The charm, the smile, the personality ... it shines right there,” he said.

Arvinder, a young woman in her early 20s in India, was also love-struck by Harbinder’s picture. She saw the New Yorker’s kind, loving eyes — a smile that seemed to be directed at her.

A thing as simple as looking at an old-fashioned, physical photograph sparked a whirlwind romance and a lifetime of love — all of it captured in a five-minute documentary, “At First Sight,” posted online and shown as part of a larger series at the Tribeca Film Festival in April. But it wasn’t just a heartwarming tale — it was also a subtle pitch for photo printers, with the YouTube version ending with the tagline, “What memories will you print?” followed by “HP keep reinventing.”

Since the dawn of TV, entertainment and advertising have been closely intertwined. In the 1950s, companies sponsored programs such as “The Colgate Comedy Hour,” where it was common to hear pitches for household products before the show and even see them mentioned in the program’s narratives. But as technology evolved, more consumers fast-forwarded through ads and cut the cord altogether. Brands sought out viral video content that they could sponsor on social media, fueling the growth of companies such as BuzzFeed and Vox. Now, they are going a step further by partnering directly with filmmakers.

Whether the aim is to encourage people to buy photo printers, athletic shoes or even fried chicken, companies such as HP, Nike and Church’s Chicken are increasingly pouring money into documentaries in hopes of capturing the attention of consumers who shun traditional commercials. The trend has been a boon to local filmmakers such as East Hollywood’s Dirty Robber. But it has also stirred debate over the role of advertising in nonfiction storytelling.

“As most audiences have fled [watching commercials on traditional television], you really have to reimagine how you are going to communicate with people.… A documentary is a really nice way,” said James DeJulio, chief executive of Tongal. The Santa Monica firm runs a platform that connects creators and other talent with entertainment companies and brands.

Funding remains a challenge for documentary filmmakers, who often rely on grants. Corporations can provide an additional investment boost, said Caty Borum Chattoo, director of American University’s Center for Media and Social Impact in Washington, D.C.

Last year, 26% of documentary directors and producers said they planned to work on branded documentaries sponsored by a company, according to a study by the center. “Documentary filmmakers are interested in diversifying their potential forms of revenue and funding,” Borum Chattoo said.

For their part, companies say they believe sponsored documentaries are effective at reaching newer audiences.

“The key to standing out from the noise is to tell stories that are genuine and connect with people,” said Angela Matusik, HP’s head of brand journalism.

The Palo Alto company, which sells photo printers, is hoping its films will “encourage people to print more photos.” Already, 77% of viewers who were surveyed said “At First Sight” was effective in making them feel that way, Matusik added.

People don’t care who is paying for it, so long as it’s meaningful … so long as it’s storytelling.

— Martin Desmond Roe, co-founder of Dirty Robber

In the HP films, New York-based Redglass Pictures promoted the power of printed photographs through three real-life tales — a love story, a mystery and a discovery.

“An idea of love at first sight felt like such a great way to honor this idea of love through photographs,” said Sarah Klein, co-founder of Redglass Pictures. “We wanted to tell the story of a version that really did happen through a photograph that did result in true love.”

For brands, paying for documentaries can be cheaper than paying for TV ads in large national markets.

Church’s Chicken said it spent $10,000 to $20,000 for each of the several documentary videos it has commissioned. In 2016, the Atlanta fast-food chain posted a five-minute YouTube video on Compton, highlighting community members explaining what Compton means to them and briefly touching on the role of Church’s Chicken in their city — as one of the few establishments that survived the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Church’s also launched a docu-series on the World’s Fastest Drummer competition — because drumming could be loosely tied to drumsticks.

The drumming series allowed the company to get in front of a younger, 18-to-35 male demographic that it wouldn’t have been able to reach with traditional media, said Georgia Margeson, senior director of advertising at Church’s.

“This is a way that you can reach out to communities and establish a voice among consumers that you may not have reached otherwise,” Margeson said.

Local documentary filmmakers such as Martin Desmond Roe, a co-founder of Dirty Robber, have benefited from the increased interest from brands such as Nike. Last year, brand-related projects made up half of his production company’s yearly revenue — in the range of roughly $15 million. His company has worked on branded documentaries including “Breaking2,” a film about marathon running paid for by Nike that has received more than 5.5 million views on YouTube.

“It’s where our skill set meets their need,” Roe said. “People don’t care who is paying for it, so long as it’s meaningful … so long as it’s storytelling.”

Roku, a Los Gatos-based maker of TV-connected devices and host of its own ad-supported streaming channel, says there is strong demand among consumers for branded videos. Last year, the company launched its own branded content hub on the Roku Channel, getting content from brands in front of Roku customers and on the biggest screen in their living rooms. In return, Roku receives revenue based on how many households the branded content hub could reach.

“For them, it was truly an opportunity to not only get scale to an audience they were looking to reach but to find a more engaged user, a cord cutter, someone they simply couldn’t reach in the living room any other way,” said Alison Levin, Roku’s vice president of ad sales and strategy.

The first videos to launch on the Roku Channel’s branded hub were explorer stories sponsored by beer company MillerCoors. Roku viewers watched about 70% of those videos to completion whether they were one or six minutes long, Levin said. Customers spent more than 851,000 minutes with the videos from September through December, she added.

“The fact that we saw consumers pick to watch it and almost watch it to completion shows how much they value that content,” Levin said.

But branded video challenges the very nature of documentary storytelling, said Simon Kilmurry, executive director of the International Documentary Assn.

“The strength of documentary film is that it’s independent,” Kilmurry said. “When you begin to get brands involved, it becomes much murkier in terms of what the motivations are.”

Traditional outlets that broadcast documentaries, such as PBS, have strict requirements for sponsor disclosure, often vocally disclosing major sponsors at the start of films. But when it comes to social media or some streaming platforms, those disclosures may not be as obvious.

With branded content, filmmakers have to balance sponsor visibility with effective storytelling.

In 2017, Dirty Robber released a 55-minute documentary for Nike that illustrated athletes attempting to run a marathon under two hours. None of them met the goal, with one runner missing it by just 26 seconds. The company said it shot footage of Nike shoes getting made for the marathon, but opted to not include it because it took away from the storytelling. Nike agreed, and the documentary that ran on YouTube instead focused on the struggle the runners faced to beat the clock. (Nike did not respond to a request for comment.)

Dirty Robber held similar conversations with stakeholders in a docu-series on rapper Wiz Khalifa that was distributed on streaming music platform Apple Music in April. The series of videos, which ran less than 15 minutes each, were originally envisioned to show Khalifa’s activities over a week. But Dirty Robber wanted to tell the story of Khalifa’s relationship with his friends, parents and son and how that has evolved as he’s become a prominent rapper. The company declined to disclose the cost of the project, which was financed by Apple.

“Now it’s not just branded content for the fans,” Roe said. “Now, it’s real storytelling.”

Twitter: @thewendylee

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.