Solar is in, biomass energy is out—and farmers are struggling to dispose of woody waste

California’s biomass energy plants, which burn woody waste to generate electricity, are folding in rapid succession.

- Share via

Reporting From Fresno — It should have been a good year for turning wood and waste into electrons.

A record-setting drought forced growers to bulldoze thousands of acres of trees, and hardly anyone in the Central Valley has permission to light bonfires anymore.

But more than trees have withered in California’s sun. The state’s biomass energy plants are folding in rapid succession, unable to compete with heavily subsidized solar farms, many of which have sprouted up amid the fields and orchards of the San Joaquin Valley.

Paul Parreira is painfully aware of the irony. The third-generation grower and almond processor is running out of dirt roads where he can spread ground-up almond shells, even as he expands a one-megawatt solar array on six acres of his family’s property in Los Banos.

The waste-to-energy facilities where Parreira used to send about 50,000 tons of shells per year are vanishing. Six have closed in just two years, the latest in Delano, which shut down Thursday, after San Diego Gas & Electric ended its power purchase agreement. Twenty-five people were laid off, and 19 will remain to complete closure of the plant, said Dennis Serpa, fuels manager of the 50-megawatt plant, owned and operated by Covanta.

The Rio Bravo biomass facility south of Fresno is taking some of the fuel that would have gone to Delano. But short of a miracle, the 25-megawatt plant run by IHI Power Services Corp. will burn its last wood chips in July, when its power purchase agreement with Pacific Gas & Electric Co. expires.

The Sacramento Municipal Utility District, meanwhile, is locked in a dispute with the 18-megawatt Buena Vista biomass facility in Ione, and has threatened to terminate its contract, according to district spokesman Christopher Capra.

The closures have forced the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District to consider allowing more agricultural waste to be burned in open piles, which produces particulate matter and ozone-forming compounds associated with cardiovascular illnesses.

Air quality already is notoriously bad throughout the district — four of the five dirtiest metropolitan areas, based on ozone and particulate measures, are in the valley, according to the American Lung Assn. Based only on measures of particulate matter, the Fresno-Madera area was the worst in the nation, followed by Bakersfield, Visalia-Porterville-Hanford, and Modesto-Merced.

A policy change on open burning would require extensive public hearings. But the district may have little choice.

“Do not underestimate the fact that state law requires that if farmers do not have an economically feasible alternative, the district is prohibited from banning the open burning of those materials,” Executive Director Seyed Sadredin cautioned the district’s governing board at its November monthly meeting. “We have 11 farmers right now that are risking the loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars if they do not find a way to dispose of that material.”

No one expects a wholesale return to bonfires wafting smoke across the Central Valley. But without the revenue from selling farm waste to the biomass plants, the costs of clearing agricultural debris are expected to skyrocket.

“It’s going to triple the cost to farmers,” said Frank Sanchez, who owns a tree-grinding service that is one of the top customers at Rio Bravo. “They’re going to be paying about $1,000 to $1,200 an acre just to do the same work that you were doing before for about $300 an acre.”

Sanchez pared his profit margin to zero in October, hoping to keep his clients until the market improves. If it doesn’t, he’ll lay off as many as 30 workers from his Wasco-based company.

Tejon Ranch, one of his clients, knocked down 160 acres of almond trees in 2015. But the debris will stay on the farm. “For 160 acres, you’re looking at 200 or so truckloads,” said Trey Irwin, vice president of agriculture for Tejon, a conservancy that has a strict no-burn policy. “It’s pretty hard to find a home for 200 truckloads.”

Some growers have begun experimenting with a more advanced farm-scale technology, but it could be a decade or more before those can be scaled up, industry experts say.

“The new technology is just not developed yet to the scale that we are,” said Rick Spurlock, general manager of the Rio Bravo Fresno plant. “We are a utility-scaled plant. We’re handling 200,000 tons of fuel. It would take 25 of those facilities to equal one of these facilities.

“But problem is, that future is 10 to 15 years away and the problem we have is today.” The experimental plants burn about 100 pounds of hulls per hour, while the largest biomass plants can handle a ton per hour.

Meanwhile, the incentives to switch to solar are strong. Parreira broke ground on his one-megawatt plant five years ago, when he could get a subsidized rate of 15 cents a kilowatt-hour.

“I’m here to tell you, there was a whole bunch of welfare that went along with that deal,” Parreira said. But, he added, “You can certainly argue that biomass had its day in the sun, 20 years ago, when it had its subsidies.”

Biomass-to-electricity plants — essentially hyper-efficient wood furnaces linked to steam turbines — owe their existence to federal alternative-energy mandates enacted on the heels of the 1970s energy crisis. In the 1980s, more than 60 biomass plants in California turned 10 million tons of woody waste into about 2% of the state’s electricity, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. By the turn of the century, the industry already had contracted by more than a third, amid deregulation of California’s grid, according to the lab.

By 2011, California’s biomass industry faced a cliff. Its long-term contracts and a key subsidy paid by ratepayers were about to expire. New purchase agreements would be tied more closely to the cost of natural gas, and those prices were plummeting.

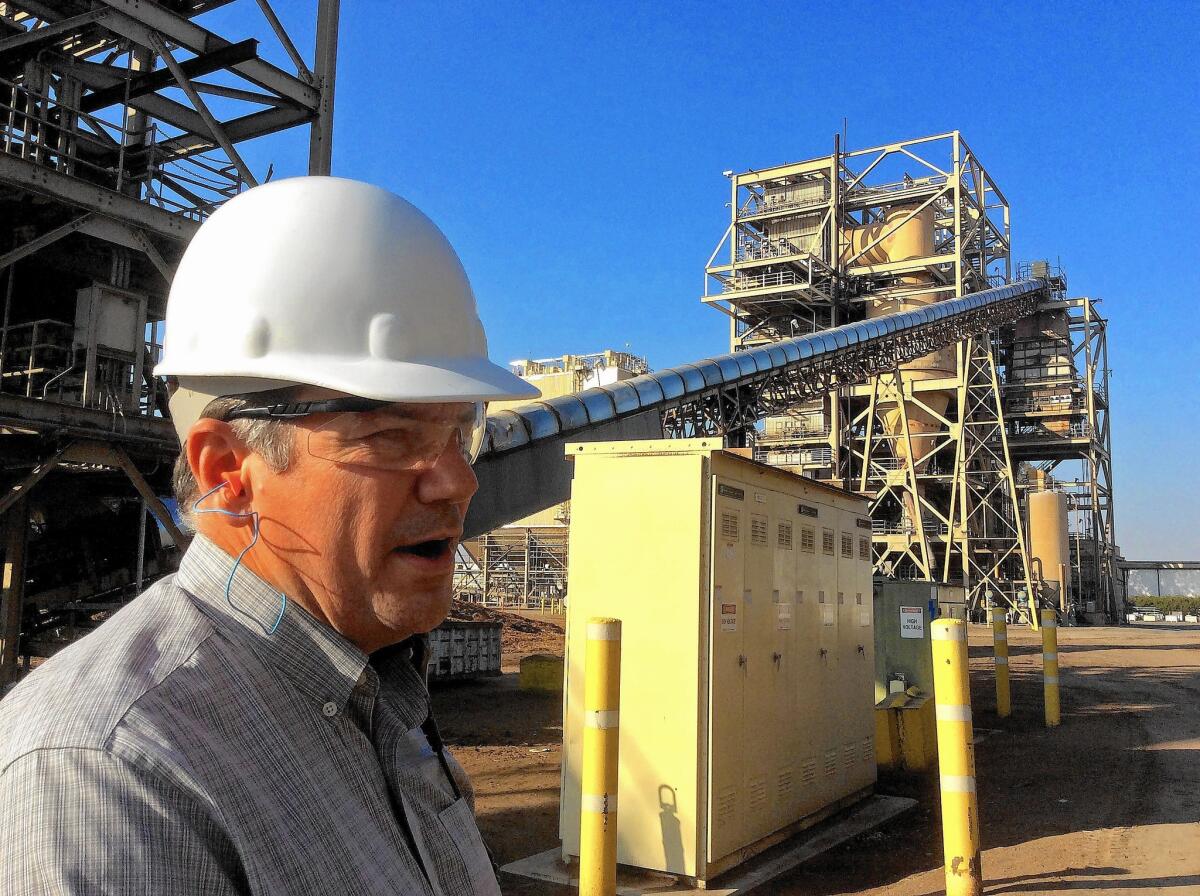

Rick Spurlock holds some of the ash residue that is repurposed as ground cover for dairy cattle facilities.

Pacific Gas & Electric Co. renegotiated purchase agreements with Rio Bravo and another facility in Mendota, along with three others in Northern California. The utility agreed to pay a higher rate in exchange for an earlier exit from contracts. San Diego Gas & Electric got the same deal from Delano.

Now down to 25 plants with a capacity of 611 megawatts, the biomass industry is taking its case to Sacramento, bolstered by Gov. Jerry Brown’s latest drought-related emergency proclamation. It touts biomass energy generation as a solution to culling dead trees that pose a wildfire threat in the Sierra Nevada. The San Joaquin Valley facilities are a short distance from the most browned swaths, advocates note. They are hoping for some direct funding or a way to pass costs to utilities, and ultimately to consumers.

Advocates for biomass say utilities and their regulators should factor other benefits of biomass into the rates — the plants prevent pollution from open burning and help municipalities comply with state rules to reduce landfilling.

“With wind and solar, you just get electrons,” said Julee Malinowski-Ball, executive director of the California Biomass Energy Alliance, an industry advocacy group. “With biomass you get all this added benefit.”

Utilities aren’t buying it.

“We have not made a conscious decision to back away from biomass contracts,” said Stephanie Donovan, spokeswoman for San Diego Gas & Electric Co. “We have had a philosophy of being technology agnostic. What we really are looking for is the least-cost, best-fit resource.”

PG&E said its renegotiations with biomass providers were not motivated by a desire to terminate contracts early. The utility “buys more bioenergy than any other energy purchaser in California, with biomass accounting for 17% of our renewable portfolio currently,” said spokesman Denny Boyles.

To protect ratepayers, biomass “must be competitive with alternative renewable resources,” Boyles said. “Our contract terms are reviewed and approved by the CPUC to ensure that they balance the interests of obtaining more biomass generation at reasonable prices and under reasonable terms.”

Twitter: @LATgeoffmohan

ALSO

Transforming the end of the 2 Freeway could be the beginning of a new L.A.

2-car crash in Ontario kills 5, including a 6-year-old boy

Advocates push for the U.S. Postal Service to offer basic banking

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.