Facebook, Yelp clash with California homeowners over plan to dramatically boost development

- Share via

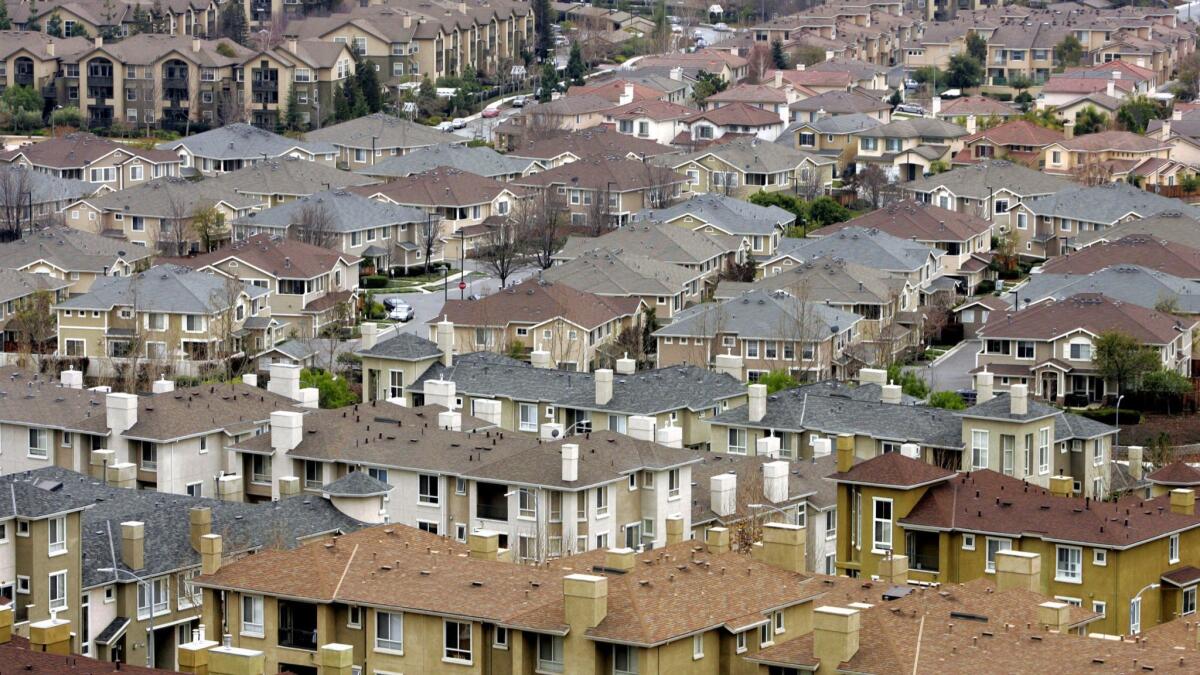

California is bracing for a high-profile fight over the state’s housing crisis. And the clash is pitting Silicon Valley technology executives, who want to cut regulations that make it hard to build multi-story apartment buildings, against existing homeowners and affordable housing advocates.

The housing crunch, particularly acute in Bay Area cities such as San Francisco and San Jose, is a problem that the tech industry helped create by attracting well-paid new workers who can outbid longtime residents. That, combined with zoning restrictions, has helped to push up housing prices to the highest in the nation, with a median price of $1.3 million in San Jose, according to the National Association of Realtors. Los Angeles, home to Snap Inc., is in similar straits.

At the same time, the technology sector is frustrated with the limited housing supply and high prices in its home state that make it difficult to recruit workers and foster a diverse community. It has spent years building the political machinery to push for change: It has state and local lobbying groups, a long list of donors and favored politicians.

Now, it also has a sledgehammer of a bill, which would force California cities to allow new multi-story apartments to be built near public transportation. The bill — SB 827, introduced this year by state Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) — is set to be one of the most contentious pieces of legislation in Sacramento this session. The Los Angeles City Council recently voted unanimously to oppose the bill.

A new guard of powerbroker chief executives has put their names and wealth behind the pro-growth movement that’s laying the groundwork for the bill, including Twitter Inc. Chief Executive Jack Dorsey, Stripe Inc. co-founders Patrick and John Collison, Lyft Inc. CEO Logan Green, and Yelp Inc. CEO Jeremy Stoppelman.

Facebook Inc. is getting on board, too. “Facebook supports legislation that spurs the creation of new housing near high-quality transportation to reduce traffic congestion on local roadways,” Ann Blackwood, Facebook’s state and local public policy manager, said in a statement.

They’re up against neighborhood preservation groups and affordable housing activists who for years have dominated housing policy in the Bay Area.

Neighborhood councils often block new construction projects, since locals want to preserve the city’s charm and, critics say, impose artificial limits on housing inventory that keep home values rising. They fear the bill would lead to the “Manhattan-ization” of the Bay Area, with towering buildings casting shade on iconic single-family Victorian homes.

It’s about damn time that the tech sector started to engage in housing policy.

— Calif. State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco)

What’s more, they argue that the new construction won’t help with lowering costs because their proximity to public transportation will make them “premium” rentals.

“It’s about damn time that the tech sector started to engage in housing policy,” Wiener said in an interview. “This is a major industry in our state. It employs an enormous amount of people and the tech sector, like other economic sectors, relies on the health of our state to succeed.”

At the end of 2017, 56% of households in the U.S. could afford the median-priced U.S. house, according to the California Association of Realtors. But only 21% of people in the Bay Area can afford the median-priced house there, which rose to a record $825,000 in November.

To address that problem, with Stoppelman at the forefront, Silicon Valley is bankrolling the YIMBY movement — Yes in My Backyard — a network of pro-housing, pro-development groups.

“In California, we have dug ourselves into a massive housing hole in the last 50 years by making it progressively harder to build housing by making it more time consuming and expensive,” says Brian Hanlon, who heads the California YIMBY group. “We’re past the point of viewing housing as a pure local issue. It is a statewide concern.”

California YIMBY has raised more than $1 million and has a registered lobbyist on its payroll. The group hopes to collect another $1.5 million this year, Hanlon says. He estimates that about 90% of the money has come from technology executives.

Marco Zappacosta, the 32-year-old CEO for the local services start-up Thumbtack Inc., is a contributor. “Technology companies have such insane margins that they’re one of the few sectors that can continue to be viable in this environment — Google and Facebook and all of us are going to continue to be OK,” he said. “The real question is do you want plumbers and cleaners and baby-sitters?”

A mix of self-interest and shared ideology is motivating the tech industry’s housing obsession. Companies such as Lyft and Pandora Media Inc. have moved their customer support offices away from Silicon Valley to save money. Thumbtack has opened offices in Salt Lake City, where it is cheaper to live and to hire workers. The company also has a team of remote contractors in the Philippines.

And while tech workers are generally free-market minded, in the battle for housing they’re also taking a moral stand. The tech industry’s high-profile role championing the legislation comes amid rising scrutiny of companies — from Facebook to Google — and a tech backlash.

The bill’s critics come in various stripes. Homeowners and neighborhood groups worry that the legislation will negatively alter the character of historic neighborhoods. Other opponents say the bill will just encourage teardowns and evictions and ultimately create more high-end housing. Without protections such as rent control, they say, new, taller apartment buildings will cater to the area’s wealthy residents and attract more tech interlopers.

“There’s a whole lot more money, as Scott Wiener has shown, in trying to gentrify communities,” says Damien Goodmon, director of the Housing is a Human Right campaign. He compares the proposal to an “Ayn Rand, trickle-down” housing philosophy that assumes that more high-end housing supply will somehow help the poor.

“The market is not going to build to a level that’s affordable,” he said.

The bill’s drafters say that they’re in the process of revising the legislation to avoid unintended side effects, mitigate some local concerns, and to win over more supporters. Protections have been added that would make it more difficult to tear down housing that already has affordable units.

As proposed, the new housing could be as much as eight stories high, depending on the location, though many would be just three stories tall, Hanlon said. The bill also eliminates local requirements that new housing projects near public transportation create additional parking spaces.

“The bill is a work in progress,” Wiener said. “We definitely have a winding path ahead of us and a lot of people to convince.”

Newcomer writes for Bloomberg.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.