How I Made It: Bruce Meyer’s road to success from candle wax to classic cars

- Share via

Bruce Meyer was a long-haired hippie, just graduated from UC Berkeley, when he suggested that his family expand their Gearys gift boutique to include candles and a mail order business. That began a retail revolution that made Gearys one of the premiere Beverly Hills shopping destinations, and fueled Meyer’s decades-long obsession with cars that led to the founding of the Petersen Automotive Museum.

The secret life of a rider and racer

Automobiles were not in Meyer’s blood. His grandparents never owned cars, he says, and his parents thought they were a waste of time and money.

But the impressionable young man grew up near the old Art Center College of Design campus in Hancock Park. Many of the students were GIs just returned from the war. They all drove hot rods, which imprinted heavily on Meyer. He decided he’d own one, someday.

Still, his first motor vehicle was a motorcycle — a 1950s BSA scrambler that he bought for $100 and kept hidden in a friend’s garage. Soon he was sneaking out on the weekends to race, keeping his hobby a secret from his disapproving parents.

“They knew nothing about it,” Meyer says. “I was the perfect son. I never got into trouble. I obeyed. I worked hard. So I couldn’t let them know about the motorcycles.”

Meyer always had side jobs. He remembers selling the Hollywood Citizen-News from the grass median at the corner of Highland and Melrose avenues, and adding $3 a week to his regular 50-cent allowance.

At Berkeley, where he got a bachelor’s degree in business, he bussed tables, tended bar and had a gig selling embossed stationery to sororities. Then he discovered that the university would extend interest-free student loans to undergraduates. Meyer borrowed money, bought motorcycles, raced them on the weekends, and then sold them for a profit.

Education of a young retailer

After Berkeley, and a couple of seasons bartending in Lake Tahoe, Meyer came home.

His father, Fred Meyer, had transitioned from a career selling appliances to owning the small Gearys gift store in Beverly Hills. Bruce was sent to Michigan to train in a department store, then started working in the family business.

Soon he had talked his parents into letting him open a boutique selling candles and incense — it was the 1960s — and a mail order business. From candles, the boutique included posters, which turned into a gallery offering original artworks.

When the building came up for sale, Meyer overcame his parents’ objections and spent money to acquire the property. That was the first of many real estate investments. Now Meyer’s company owns vast holdings in Beverly Hills, Pasadena, Newport Beach and Santa Barbara.

“I didn’t have any plan to be a big retail king, or a real estate king,” he says. “But when my landlord offered me the building, it seemed the right thing to do.”

Birth of the Petersen

Meyer’s first new car was a Porsche, but he eventually got a hot rod. Interest in that car, and the proximity of their Beverly Hills galleries, introduced him to Robert Petersen, publisher of Hot Rod magazine.

Their shared obsession with high-powered automobiles led to their partnering with the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum — both men were board members — to buy an empty department store property on Wilshire Boulevard and turn it into the Petersen Automotive Museum.

Meyer became its first chairman, and would go on to serve multiple terms as a museum officer. Today the Bruce Meyer Family Gallery features many cars from his private stock.

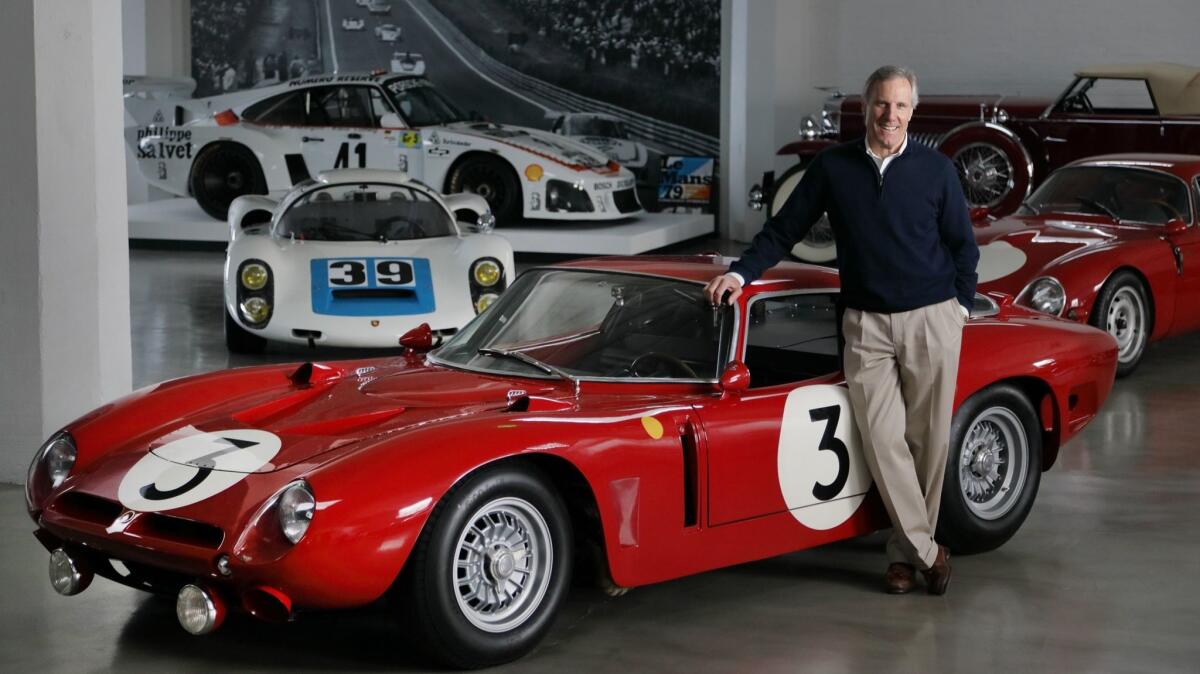

Meyer insists that his personal collection isn’t really a “collection,” and that he isn’t a collector in the traditional sense — despite the Le Mans-winning Porche 935 and Ferrari 250 GT SWB, the Ferrari 250 TRC Testa Rossa driven by Phil Hill and Carroll Shelby, and the 1932 Ford Hi-Boy coupe he bought from the late Dan Gurney.

“I just buy cars that are attractive to me,” he says. “I bought hot rods when people thought they were junk. I never even thought about those as ‘collectible.’ ”

A high-energy human

Meyer is a man who likes being busy. He has set land speed records at the Bonneville Salt Flats, been a trustee for the University of California and served on the boards of the California Highway Patrol’s 11-99 Foundation and St. John’s Health Center Foundation.

“I’ve always had a lot of energy,” he says. “I’m not a reader. I don’t go to the beach. I’m not a golfer. I just enjoy work and activities more than other things.”

He insists he has no personal credo, but friends kid him about the motto “Never lift,” which has followed him around the automotive world.

Meyer says he adopted the phrase from famed Indianapolis 500 driver Parnelli Jones, who once told him a story about giving an ambitious young racer this advice: The secret to winning races, he told the youngster, was never taking your foot off the gas pedal. The young driver applied that advice, and promptly crashed his car.

“Parnelli said he was just kidding,” Meyer says. “But it stuck with me. I sign my letters that way — Never Lift — and I see my life that way. You just keep going. You don’t give up. Try and keep your foot down, whatever you’re doing. But of course it’s not the way I race cars! That would be crazy.”

More success stories from How I Made It »

There is no greater advocate for the car hobby than Bruce Meyer. His passion has influenced an entire generation of car people.

— Petersen Automotive Museum Chairman Peter Mullin

The secret to successful car collecting

Meyer says he has no interest in bargains or barn finds. Instead, he says, the key to collecting classic vehicles is to buy only what you love, pay whatever it takes to acquire it, then pay top dollar to restore it.

To pay below market price, or find the hidden bargain, or take a short cut on restoration, is to invite further misery.

“My motto is, ‘Buy the best example of what you want, and pay whatever it takes. That way, you cry only once.”

The true key to happiness

Meyer’s fraternity brother was H. William Harlan, who would later found the Harlan Estates vineyards of Napa Valley. Meyer remembers Harlan’s ambitions and his systematic approach to success.

“Bill had plans,” Meyer recalls. “He had a five-year plan, and a 10-year plan. It was amazing to me, because I had never even heard of such a thing. And I had absolutely no plan at all.”

Did that change later, once he entered business?

“The answer is no — not at all,” Meyer says. “If you keep your expectations low, you will always exceed your expectations. That’s been the key to my happiness. I’ve exceeded my expectations in every area of my life.”

Family man

Meyer met wife-to-be Raylene in 1968 and they married soon after. Together they raised three children.

Just over a year ago, when he turned 75, Meyer says, he decided to stop racing.

“I have entered preservation mode,” he says. “I’ve stopped motorcycling. I’ve stopped skiing. I’ve stopped running Bonneville. I just don’t want to fall down anymore.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.