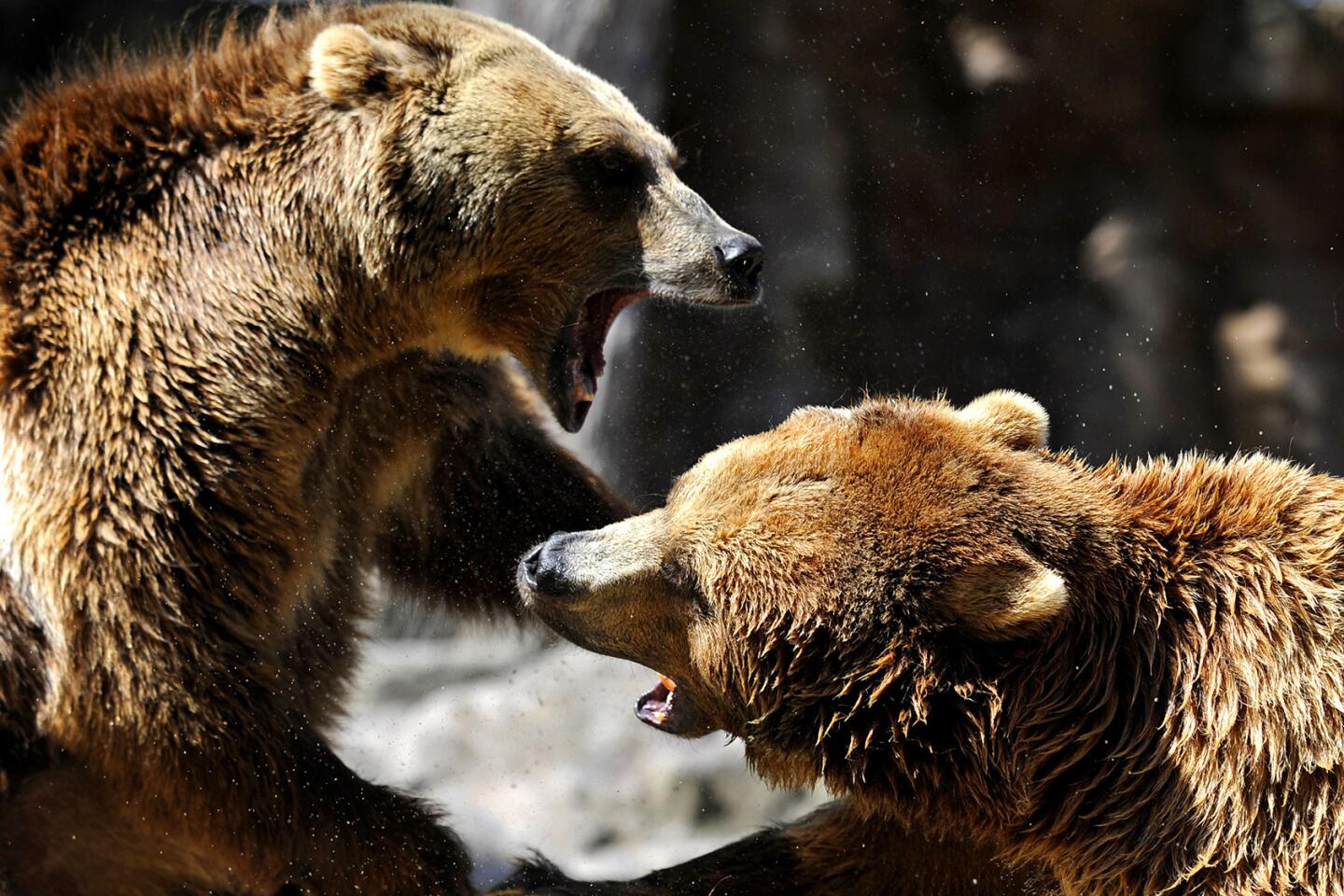

New bear market threat forces the issue: How much can you stand to lose?

- Share via

Game over?

The turmoil that has racked financial markets for the last two months has stoked fears that stocks’ six-year-long bull run has ended — and with it, hopes for a continuing economic recovery.

For tens of millions of Americans who own stocks in retirement savings plans, the prospect of suffering through a horrendous market decline like the 2008-09 plunge is chilling. Retirees, in particular, may rightly figure that they don’t have time to endure another round of deep paper losses and wait for a rebound. For businesses, a severe slump in share prices could sap confidence and corporate spending.

Yet many Wall Street pros warn against jumping the gun. The benchmark Standard & Poor’s 500 index through Friday was down 8.6% from its peak. That is far short of the minimum 20% drop that would be considered a new bear market, and just a sliver of the 57% crash of 2008-2009.

Even so, the simple nest egg advice that has worked well for six years — “just leave it alone” — may not suffice for some investors. The forces weighing on stocks, including global economic fears, weak corporate earnings and expectations of rising U.S. interest rates, haven’t diminished. That makes it a good time for a financial reality check to better prepare yourself for whatever markets bring:

First, realize that you have time to act. If this is a bear market, it’s early. Many individual stocks in industries including biotech, energy and heavy machinery have fallen more than 20% from their 2015 highs. But that has been offset by much more modest losses in sectors such as utilities, home builders, food, defense and technology.

The result is that most well-diversified portfolios haven’t yet given up much, on average. The typical mutual fund that owns a mix of U.S. large-company stocks was down about 7.5% in the third quarter and is down 6.5% year to date, according to Morningstar Inc.

To put it another way, most of the gains investors made in U.S. stocks since 2009 still are intact. In the last five years alone, the S&P 500 is up 71% through Friday.

Bonds are providing a buffer. Millions of people invest via so-called target-date retirement funds in their 401(k)s or other savings plans. The funds typically hold a mix of stocks and high-quality bonds. This year, many of those bonds have generated modestly positive returns that have helped offset the funds’ stock losses.

So as an example, the average target-date fund designed for someone expecting to retire between 2026 and 2030 is off 4.6% year to date. A bummer, but not crippling.

Giles Almond, who manages $250 million for clients at Matrix Wealth Advisors in Charlotte, N.C., says that for investors who want to keep things very simple, “The old 60/40 mix of stocks and bonds can still serve you pretty well.”

Not every scary stock sell-off becomes a bear market. In fact, most don’t. Since this bull market began in March 2009 there have been seven declines of 7% or more in the S&P 500, excluding the current slide, according to Yardeni Research Inc. Only the sell-off of 2011 came close to the bear market threshold; it ended with the index down 19.4% before rebounding.

One popular argument for a new bear market is simply that the current bull market is old. This now is the third-longest bull run since 1930, at 78 months. But James Stack, a money manager and market historian at InvesTech Research in Whitefish, Mont., says bull markets “don’t die of old age alone.” It takes some fundamental problem — say, soaring interest rates, or the onset of recession.

Many of the most important U.S. economic indicators still point to growth. Consumer spending rose 0.4% in August, the same healthy pace as in July. The Conference Board’s leading economic index remains in an uptrend. Car sales soared in September. And the economy still is creating jobs, though the September net job gain was a disappointing 142,000 positions.

Now the bad news: Corporate profits are fading. Wall Street pays particular attention to the earnings of the S&P 500 companies, which comprise most of the nation’s biggest publicly traded firms.

By that yardstick 2015 is set to show the first annual decline in profit since 2007 — down 1.8% this year from last year’s record high, according to estimates from Standard & Poor’s.

One major drag on the profit total is the plunge in energy-sector earnings caused by the collapse of oil prices. But profits also have weakened for companies in other industries, including utilities, industrial goods and some consumer products. It makes sense that a decline in profits would trigger a decline in share prices as well.

The struggling global economy also is depressing profits. Europe and many developing economies have been stuck in low gear, or worse. That has led to the devaluation of foreign currencies against the dollar. Weak foreign economies prefer that their currencies decline in value because it makes their exports cheaper abroad. That, in turn, means tougher competition for U.S. exporters, squeezing earnings.

What’s more, devalued foreign currencies mean the sales and profit that U.S. firms generate abroad translate into fewer dollars when brought home. That’s another drag on the bottom line.

The biggest bomb in the currency wars exploded in mid-August, when China pushed its tightly controlled currency down 2% against the dollar. Though a small move, the drop deepened fears over China’s economic slowdown. Within days Chinese stocks dived, taking other world markets with them.

U.S. stocks aren’t cheap by classic measures. One closely watched barometer is the market’s price-to-earnings ratio, or stock prices divided by underlying earnings per share. The higher the number, the more expensive the market. The S&P 500 now is priced at 17.6 times estimated 2015 earnings, compared with the 10-year average of 16.8.

Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Wells Capital Management in Minneapolis, says investors logically are ratcheting down what they’re willing to pay for stocks. Amid rising global uncertainty, he says, the new “right level” for the average price-to-earnings ratio may be closer to 15 than 18.

The Federal Reserve looms over everything. Until stocks worldwide began to unravel in August, many investors had expected the Fed in September to raise its benchmark short-term interest rate for the first time since 2006. Instead, the central bank left the rate near zero, in part citing “developments abroad.”

But if the U.S. economy continues to expand, the Fed has made clear it will soon begin raising its rate, albeit slowly — perhaps just to 0.25% initially.

The crucial question is whether even a single small increase could cause a stock panic and, at the same time, devalue fixed-rate bonds by pushing up longer-term market interest rates. That would be a double whammy for investors.

Some market veterans warn investors against trying to convince themselves that the risk of further losses is minimal. Rationally, people know that the stock market doesn’t like declining corporate earnings or rising interest rates, says James Bianco, head of Bianco Research in Chicago. “And isn’t that where we are?” he says.

You can’t have a crystal ball, but you can adopt a game plan to help protect yourself. The decision on whether to cut back on stocks in your portfolio should depend on when you’ll need those assets, investment advisors say. For younger people, bear markets are a gift because they allow you to buy low. But near-retirees who plan to tap their nest eggs in the next five years will need to focus more on capital preservation.

Matrix’s Almond wants clients to have enough cash and other liquid assets in their portfolio to handle living expenses during three to five down years in the stock market — to avoid having to sell low.

InvesTech’s Stack, who manages more than $1 billion for clients, has raised the cash level of his recommended stock portfolio to 27%, the highest since 2009. The idea, he says, is to have cash to buy if the market goes lower. “There are going to be some great investment opportunities in the next three to five years,” he says.

Kurt Brouwer, a principal at investment advisor Brouwer & Janachowski in Tiburon, Calif., says the goal of adjusting a portfolio after a long bull run isn’t to try to catch market highs or lows, but to make sure the asset mix matches your risk tolerance.

Investors should never think of the stock portion of their portfolio as “all or none,” he says. Rather, changes should be incremental. “If there’s something you’re really concerned about, then sell it,” he says. “And make sure anything you own you have strong conviction about.”

Most important, whatever decisions investors make in their portfolios should be part of a plan, advisors say. Think not just about getting out of an investment, but at what point you’d get back in, or into something else.

“Your plan doesn’t have to be fancy — you just have to have thought it through,” said Meloni Hallock, a principal at Acacia Wealth Advisors in Beverly Hills.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.