Honestly speaking, consumers lose in AT&T-DirecTV deal

Nobody should be surprised anymore by news of big, fat telecom mergers. AT&T’s acquiring DirecTV for nearly $49 billion is just the latest in a long line of tie-ups among phone, cable and satellite companies.

It’s the lies I can’t stand.

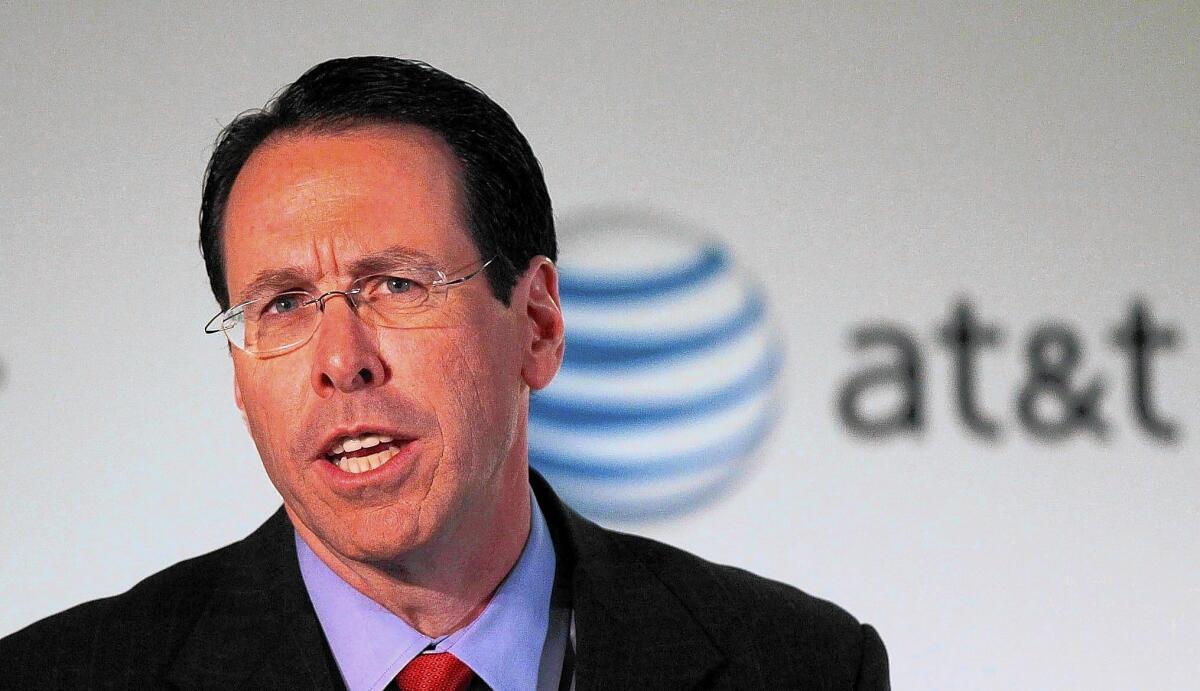

Shortly after announcing the DirecTV deal over the weekend, AT&T’s chief executive, Randall Stephenson, said that “this is going to prove to be a pro-competitive and pro-consumer transaction.”

His counterpart at DirecTV, Mike White, said that “this compelling and complementary combination will bring significant benefits to all consumers.”

Oh, please.

Why can’t these guys just man up and admit the truth: “We’re merging because this will give us more clout against the cable industry in our efforts to dominate the market.”

The giveaway wasn’t in what Stephenson and White said, but in what they didn’t say. Two words were noticeably lacking in their deal announcement: “lower prices.”

Instead, the companies touted their ability to offer “new bundles,” “a more competitive bundle” and “a better bundle” of phone, Internet, TV and wireless services.

And that’s fine for AT&T, which wants to lock people in to as many services as possible to make it harder for them to jump ship.

For consumers, however, bundles of telecom options are a far lower priority than reduced bills and better overall service.

So when Stephenson says “pro-consumer,” what he really means is “pro-company.” His company, in particular.

Craig Aaron, president of the advocacy group Free Press, said AT&T and cable giant Comcast, which has announced its own $45-billion takeover of Time Warner Cable, have nothing up their sleeves except the tired old notion that bigger is better.

“The captains of our communications industry have clearly run out of ideas,” he said. “Instead of innovating and investing in their networks, companies like AT&T and Comcast are simply buying up the competition.”

Consumers are the last thing they’re thinking about, he said.

“These companies don’t care about providing better services or even connecting more Americans,” Aaron declared. “It’s about eliminating the last shred of competition in a communications sector that’s already dominated by too few players.”

Bingo.

From a purely corporate point of view, consolidation makes a lot of sense. Fewer rivals means more ability to raise prices and not have to compete on costly fronts such as introducing new features and providing better reception.

Delara Derakhshani, policy counsel for Consumers Union, predicted that other telecom heavyweights will now feel pressure to cut their own merger deals if they want to cling to whatever market advantages they enjoy.

“The rush is on for some of the biggest industry players to get even bigger, with consumers left on the losing end,” she said.

Many Wall Street analysts believe the next likely mega-merger will be Verizon making a bid for Dish Network — a mirror image of the AT&T-DirecTV deal. On the wireless front, Sprint is expected to redouble its efforts to tie the knot with T-Mobile.

Fewer industry players, of course, means a greater likelihood that prices will go up. It’s competition that keeps prices down.

This places federal regulators in an awkward position.

If they put the kibosh on this latest round of consolidation, as was the case when the Justice Department nixed a merger of AT&T and T-Mobile in 2011, they’ll have to fend off criticism that they’re preventing telecom businesses from effectively competing in an increasingly complex digital world.

But if they approve one merger, they’ll probably have to approve them all or appear as though they’re picking winners and losers in the marketplace.

Things were more straightforward in the 1970s when the federal government filed suit against what was then American Telephone & Telegraph Co. At the time, AT&T was the largest company in the world, with phone lines reaching almost every home and business in the nation.

The Justice Department argued that all this market power was hindering competition and stifling innovation. After years of legal and political wrangling, the breakup of Ma Bell was announced in 1982, with seven so-called Baby Bells splitting AT&T’s local phone network among themselves.

Now look. The Baby Bells have pieced themselves back into a few bigger and stronger corporate entities, with one, Southwestern Bell, reclaiming the AT&T name.

No less important, the Baby Bells have largely reunited amid far less regulation than Ma Bell was subject to during its monopoly days.

“The industry is nowhere near as regulated as it used to be,” said James H. Peoples, a professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

He pointed specifically at the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Among other things, it deregulated the then-burgeoning broadband and wireless industries and gave broadcasting and communications companies the authority to enter one another’s businesses.

“Mergers like AT&T and DirecTV create economies of scale for the companies,” Peoples said. “The question is whether these lower costs are passed along to consumers. That’s the role of regulators.”

Back when Uncle Sam was breathing down Ma Bell’s neck, there was no question that consumers would benefit from any cost savings experienced by the company.

These days, not so much. Instead, the heads of AT&T and DirecTV — and Comcast and Time Warner Cable — can claim with impunity that their merger will be good for consumers. But they’re beholden to little more than their own empty words.

AT&T’s Stephenson said the DirecTV deal “will accelerate innovation and growth” and “will create a very different competitor that is going to be very good for consumers.”

He can’t really believe that.

David Lazarus’ column runs Tuesdays and Fridays. He also can be seen daily on KTLA-TV Channel 5 and followed on Twitter @Davidlaz. Send your tips or feedback to david.lazarus@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.