Column: California bill would end ‘purely profit-driven’ practice of drug-company coupons

- Share via

When it comes to fixing the dysfunctional U.S. healthcare system, state Assemblyman Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg) knows there are bigger fish to fry than drug-company discount coupons.

But as he told me: “You’ve got to start somewhere.”

Wood’s anti-coupon bill, AB 265, was approved by the Assembly last week. The legislation is now making its way through the state Senate.

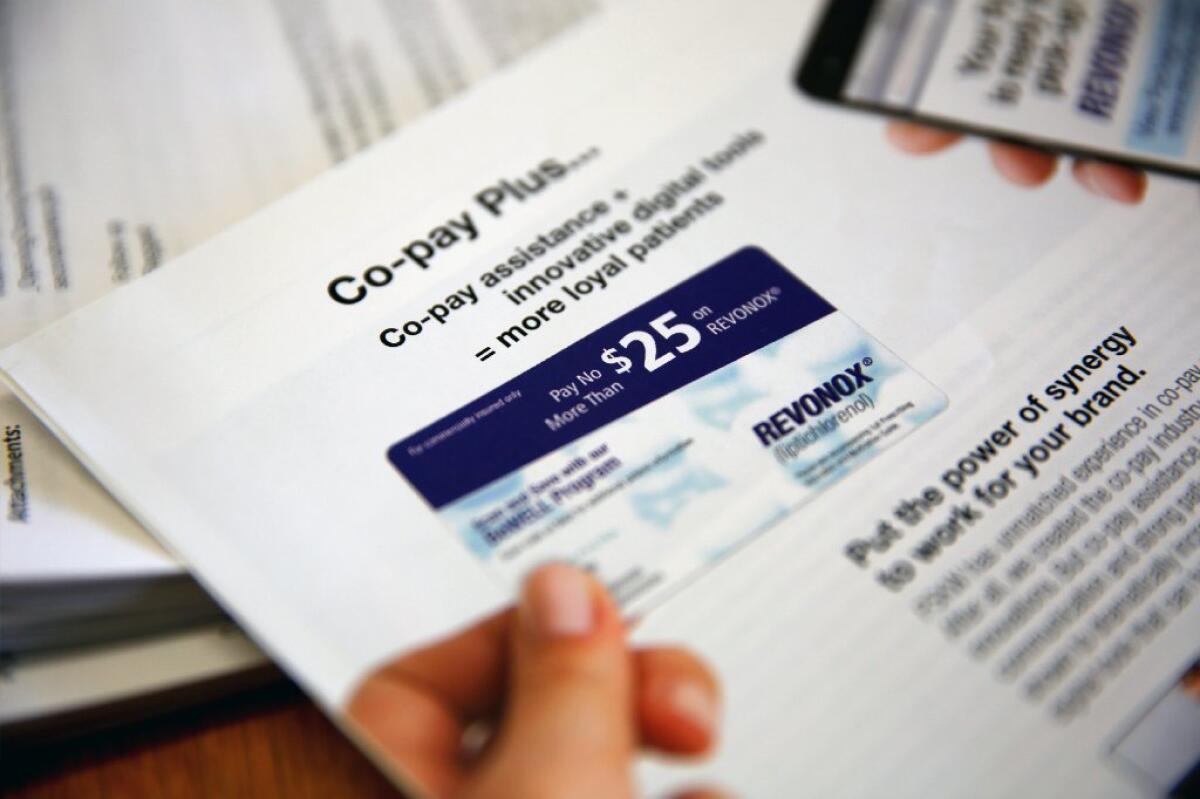

It’s a tricky business, this bill, because what it would do is prohibit pharmaceutical companies from offering discounts to patients for name-brand drugs if there’s a cheaper generic available.

“A lot of people won’t like that,” acknowledged Wood, a dentist who now serves as chairman of the Assembly Health Committee.

“When folks are offered a coupon, they’ll take it, and the drug companies know this,” he said. “What consumers may not realize is that this contributes to increases in insurance premiums.”

It’s a simple, and sneaky, marketing ploy. Rather than cut sky-high prices for name-brand meds, drug companies have found willing accomplices in patients who’d rather take the drugs they see advertised on TV than a generic equivalent with a long, unpronounceable name.

The catch is that while consumers may reduce their out-of-pocket expenses, the drug company is able to protect its overall revenue — and keep shareholders happy — by continuing to seek full reimbursement from insurers.

And that means we all pay for this dubious practice in the form of higher rates.

“This behavior is purely profit-driven,” Wood said. “The drug companies want to hold on to market share for as long as they can. But somebody has to pay for it.”

A recent study by researchers at UCLA, Harvard and Northwestern found that coupons enabled pharmaceutical companies to mask price hikes, allowing them to raise prices significantly faster than for drugs without coupons.

Spending on about two-dozen drugs sold with coupons was as much as $2.7 billion higher over five years than it would have been if the coupons weren’t used, the researchers estimated.

Massachusetts prohibited use of drug coupons if a generic equivalent was available five years ago. Similar legislation is pending in New Jersey. Federal law forbids use of such coupons by Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

Wood’s bill would bar drug companies “from offering in California any discount, repayment, product voucher or other reduction in an individual’s out-of-pocket expenses ... for any prescription drug if a lower cost generic drug is covered under the individual’s health plan.”

Matt Schmitt, an assistant professor of strategy at the UCLA Anderson School of Management and coauthor of the above study, told me that the legislation would help consumers by promoting use of generic drugs and eliminating at least one reason for insurance rate hikes.

He said drug companies have figured out that it’s cheaper and more beneficial for them to offer discounts for name-brand meds than to cut prices.

“That may be good for drug companies,” Schmitt said, “but insurers get stuck paying full cost for branded drugs, which drives up premiums for everyone.”

Not surprisingly, the drug industry has its knickers in a twist over the California bill — and is expected to mount an aggressive lobbying campaign ahead of a state Senate vote. The industry’s official position is that if coupons save people money, what’s the harm?

“This legislation is trying to solve a problem without identifying what the problem is,” declared Priscilla VanderVeer, a spokeswoman for Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, the drug industry’s main lobbying group.

The problem, of course, is that insanely high drug prices exploit a captive market of sick people, which is a predatory and deeply immoral business practice.

The average cost of prescription drugs increased nearly 9% last year, according to the Truveris National Drug Index. Over the last three years, drug prices have risen an average 10% annually.

The Financial Times reported Friday that one leading drug company, Pfizer, has raised the U.S. price of nearly 100 drugs an average of 20% so far this year. The meds include bestsellers such as Viagra and the pain medication Lyrica.

More broadly, drug costs for people under 65 will climb almost 12% this year, according to the research firm Segal Consulting. Average wages, meanwhile, are likely to grow just 2.5%.

Charging whatever the market will bear may be a sound business practice for most consumer goods. If Kanye West and Adidas can get away with a price of more than $1,000 for a pair of Yeezy sneakers, more power to them.

But the reason most other developed countries regulate drug prices is because sick people often have no choice — it literally may be a matter of life and death. As such, the market “will bear” virtually any price manufacturers set.

That’s why insulin prices have soared almost 300% over the last decade. That’s why the drug company Mylan thought it would get away with jacking up the price of EpiPens from $94 to $609.

Needless to say, Mylan responded to critics last year not by cutting the price of EpiPens but by offering a discount coupon.

I asked PhRMA’s VanderVeer if she thought prescription meds are priced fairly in the U.S.

She hesitated. “I don’t understand the question.”

I asked again: Are U.S. drug prices fair to patients?

“We care about people accessing medicine,” VanderVeer replied.

That’s nice, but access is just part of the equation. Not ripping people off is another.

Discount coupons might seem like a blessing for anyone on a tight budget. But when you factor in inevitable hikes in insurance rates, the coupons turn out to be little more than a bait and switch.

Wood called drug discount coupons “a small piece of a really, really huge puzzle,” and he’s right.

He’s also right that you’ve got to start somewhere.

David Lazarus’ column runs Tuesdays and Fridays. He also can be seen daily on KTLA-TV Channel 5 and followed on Twitter @Davidlaz. Send your tips or feedback to david.lazarus@latimes.com.

MORE FROM DAVID LAZARUS

Payday lenders, charging 460%, aren’t subject to California’s usury law

Die hard: Republican healthcare bill has no problem throwing you off a building

How to tell if a psychic is more interested in cash than clairvoyance

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.