Seeing through glass walls

ONE morning three months ago, Italian architect Renzo Piano met with a handful of LACMA trustees in one of the museum’s conference rooms. After a few minutes of small talk, Piano motioned the group over to a large table and picked up a stack of cards about 4 inches wide and 6 inches high. He began tossing them onto the tabletop, as if he were dealing blackjack.

As the cards skidded to a stop, each revealed a picture of a building, an architect or a piece of furniture from the 1950s and ‘60s. Most of the designs had a connection to Los Angeles: chairs by Charles and Ray Eames and a couple of Case Study houses with their light, almost delicate frames and wide expanses of glass.

Piano’s buildings don’t usually borrow directly from architectural precedent, so the performance seemed odd at first. But once Piano began explaining his plan for an extensive addition to the museum, it became clear that the presentation was an animated preamble to a simple declaration: He had decided to wrap LACMA’s new entry pavilion entirely in glass so that it would appear to float beneath a wide steel roof, and he wanted everybody in the room to understand that the inspiration for the design was entirely local.

That Piano decided upon glass should come as no surprise. It is, after all, the building material most intimately connected with the architecture of Los Angeles, with its energy, its light and optimism. And even today, more than 60 years after the Case Study program got underway, glass architecture seems not only entirely at home in Los Angeles but also capable of defining its future.

Indeed, in houses and commercial buildings, glass continues to exert a singular hold on the imagination of L.A. architects. The pair of towers Frank Gehry is designing for the first phase of the Grand Avenue redevelopment will be sheathed in glass with a curtain wall on the upper floors and flaring, skirt-like forms toward the base. New modular housing designs by Marmol Radziner, Jennifer Siegal, Ray Kappe and other L.A. architects — so-called modern prefab houses, which are just beginning to roll off the assembly line in significant numbers — are linked by their wraparound glass.

The aggressive use of glass in architecture wasn’t invented in Los Angeles, of course. That honor goes to the pioneering Bauhaus school architects in Germany and their successors in the U.S., including Philip Johnson. But the relationship between glass and architecture was undoubtedly perfected here — and glass, in the end, returned the favor by helping to put Los Angeles architecture on the map.

Despite the pioneering work of the Greene brothers and other residential architects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it wasn’t until images of boxy, flat-roofed new houses with floor-to-ceiling walls of glass began to circulate around the country in the 1950s that the American public really became aware of our architecture.

Indeed, once those designs were published, the world finally had a way to illustrate their daydreams about life in sunny California. It could be a photograph by Julius Shulman of a design by Richard Neutra or Pierre Koenig. It could be a Cliff May ranch house in Long Beach or a Buff, Straub and Hensman in Pasadena. Whether it was glinting in the sunlight or framing a memorable view, glass became shorthand for the appeal of America’s most thoroughly modern city.

*

What we’ve learned

There’s an inherent contradiction, of course, in Piano’s effort to move LACMA forward by looking back several decades. By making explicit reference to Southern California’s Modernist masters while talking to the LACMA trustees, he was also tapping into a deep vein of nostalgia. After all, when those donors look at examples of postwar Modernism, they see their own youth reflected back.But that’s the funny thing about the relationship of glass to Los Angeles architecture: Once you start examining it, you see contradiction, and even paradox, everywhere you look.

To begin with, you might think that a city famous for its glass architecture would be more open and more public than one filled with an imposing collection of masonry, like New York or Chicago or Paris. But even as Modern architects were bringing walls of glass to the Southern California house, Los Angeles was cementing its reputation as a place of private architectural treasures — a place that, indeed, barely had any public life to speak of, at least in the traditional sense of crowded sidewalks and comfortable park benches.

The reason for that contradiction is that floor-to-ceiling glass wasn’t primarily intended here to capture views or allow passersby to see into our houses. Instead, that sort of glass was usually installed only on the rear elevation, facing not the street but the backyard as a permeable membrane between inside and out.

There were earlier efforts to do what Piano and Gehry are doing now — to bring virtuosic glass architecture to the public sphere. Indeed, architect Albert Martin Jr., who died a month ago, did so with the Department of Water and Power John Ferraro Building downtown. With its wraparound glass sandwiched between extending floor plates, that building, especially when seen at night with its lights blazing, looks stately and weightless at the same time.

But in the end, for the most part, the marriage between glass and architecture made life here more private, not less; it kept reminding us how few reasons we had to spend time away from home.

Another paradox: The piece of glass most directly connected with our day-to-day experience of architecture in Los Angeles is the car windshield, which reveals the city, making it appear close enough to touch while keeping it at arm’s length. The windshield makes possible the drive-by architectural visit, allowing us to see and understand a building without actually walking through it. Think about how many more times, for example, you’ve seen the Walt Disney Concert Hall or the Capitol Records Building — or even the house right next door — from your car than you’ve walked through them.

Savvy architects have figured out a way to incorporate those complexities into their designs. A recent example is Jose Rafael Moneo’s Cathedral of our Lady of the Angels downtown, which was finished in 2002. The site for the cathedral is hardly ideal: It backs up to the Hollywood Freeway. But Moneo, a Spanish architect who had never worked in L.A. before, turned that difficulty into an advantage: When he designed a plaza in front of the new building, he added a glass wall to its northern edge, abutting the freeway.

The wall helps keep the sound of the cars out of the plaza, but it also offers a commentary on life in Los Angeles. Even as drivers are peering through their windshields at the building, its glass, etched with a pattern of angels, lets people on the plaza look down at the drivers. It is the cathedral’s own windshield. It transforms the sense of detachment usually promoted by glass in the city into a means of connection, all the more appropriate because it is ironic and fleeting.

*

Capturing the look

The artists in other fields who have most powerfully captured life as it’s lived in Los Angeles also use the complexity of glass to their advantage. Consider Michael Mann, whose 1995 film, “Heat,” features a character played by Robert de Niro who lives in a Malibu apartment where floor-to-ceiling glass walls offer a tantalizing view of the Pacific, trapping him in a glazed cage.Or David Hockney, for whom L.A. architecture has always been more than backdrop. A pair of his artworks illustrate with remarkable economy how the use of architectural glass in this city has grown more complex over the last several decades.

In “Beverly Hills Housewife,” a painting from 1966, Hockney gives us glass in the Eichler and Case Study tradition, with the distinction between inside and out blurred to the point of erasure. A woman in a long pink gown stands on her patio, which is decorated like a living room: There’s an animal head mounted on the wall, a zebra-skin chaise longue and a strip of grass that looks like a green carpet. The living room, instead of paintings on the walls, has windows offering perfectly framed views of plants and trees.

By the time Hockney made a photo collage called “Kasmin Los Angeles 28th March 1982,” architects such as Gehry had begun using glass in a more complicated manner, arranging it in crystalline, faceted combinations. “Kasmin,” showing the art dealer in a blue lounge chair, is a grid of 108 Polaroids that is shifting, repetitive, unreliable. The fact that Kasmin is wearing glasses — another layer of glass — distances him from us further.

*

A clear evolution

Back in the LACMA conference room, after he’d restacked his architecture cards into a neat pile, Piano explained that during his first extended stay in Los Angeles, in the 1970s, he lived in a house designed by Neutra. The transparency of the architecture had stuck in his mind more than the details of its layout or structure: What he remembered was the view and the light. The experience of spending time in that house, he added, was enough to make him appreciate Los Angeles.That sort of story has become commonplace: European architect comes to Los Angeles, is baffled at first by the packed freeways and the empty public squares, then gradually becomes entranced as he discovers the city’s remarkable collection of exquisite modern houses and their hillside views.

The encouraging difference is that Piano and other architects, Gehry chief among them, are beginning an effort to make the connection between the individual and the city succeed on a public scale. And they are using glass to do so.

In fact, in borrowing a staple of residential design for LACMA, Piano is implicitly making the argument that glass walls have become, for Los Angeles, a modern version of the classical column: an architectural building block that’s both timeless and intrinsically wedded to the culture of this city.

*

(INFOBOX BELOW)

A window into the glass city

Here are 10 buildings that use glass in memorable ways and are either open to the public or visible from the street.

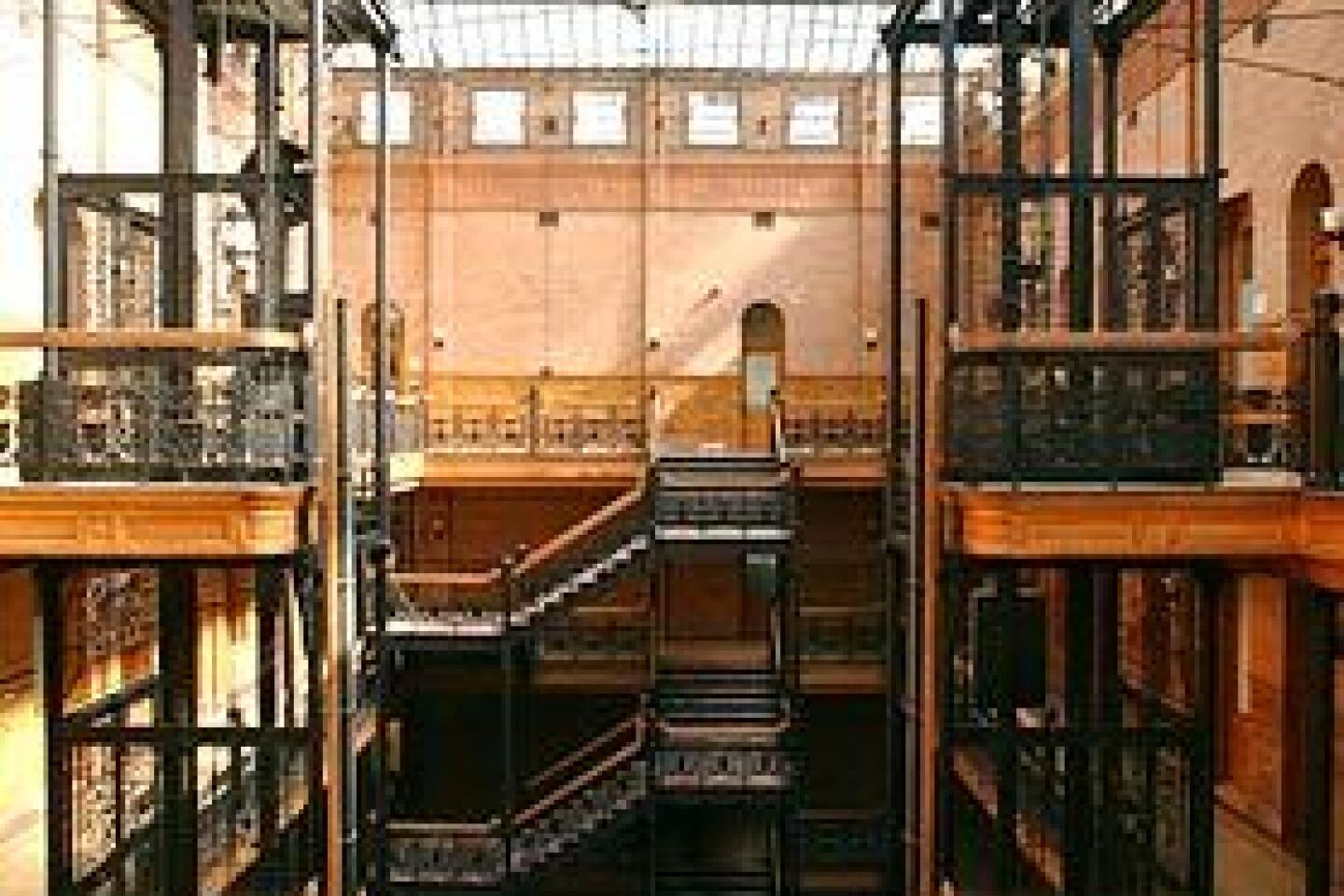

Bradbury Building

304 S. Broadway, downtown L.A.

An iron-and-glass skylight gives this 1893 office building by Sumner Hunt and George H. Wyman one of the most breathtaking interiors in the city.

Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels

555 W. Temple St., downtown L.A.

Jose Rafael Moneo added a wall of glass to the northern edge of the plaza, offering freeway views and a wry commentary on L.A. architecture.

Department of Water and Power

11 N. Hope St., downtown L.A.Albert C. Martin Jr.’s landmark sandwiches glass between protruding floor plates and seems to float at night.

Eames House and Studio

203 Chautauqua Blvd., Pacific Palisades

Extensive glass makes the division between the 1949 house and its eucalyptus-covered lot nearly disappear.

Ennis House

2607 Glendower Ave., Hollywood Hills

The dining room of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1924 concrete block design includes a mitered corner window — a thoroughly modern gesture for the time.

Gehry House

1002 22nd St., Santa Monica

Forget the chain-link: The most striking addition Frank Gehry made is the faceted glass, part glass ceiling and part skylight, to the right of the front door.

Chemosphere

7776 Torreyson Drive, Hollywood

Also known as Malin House, John Lautner’s 1960 residence features a band of flying-saucer windows.

Modular House

2914 Highland Ave., Santa Monica

Ray Kappe’s glass-filled design for the builder Living Homes is among L.A.’s first “modern prefab” houses.

Pacific Design Center

8687 Melrose Ave., West Hollywood

Cesar Pelli’s “Blue Whale” uses opaque colored glass and a roofline from London’s 19th century Crystal Palace.

Walt Disney Concert Hall

111 S. Grand Ave., downtown L.A.

Gehry added an unusual feature to the auditorium: a window, partially hidden and 36 feet high, that brings natural light into the hall during matinees.

— Christopher Hawthorne

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.