Column: More proof that a wealth tax on billionaires is desperately needed

- Share via

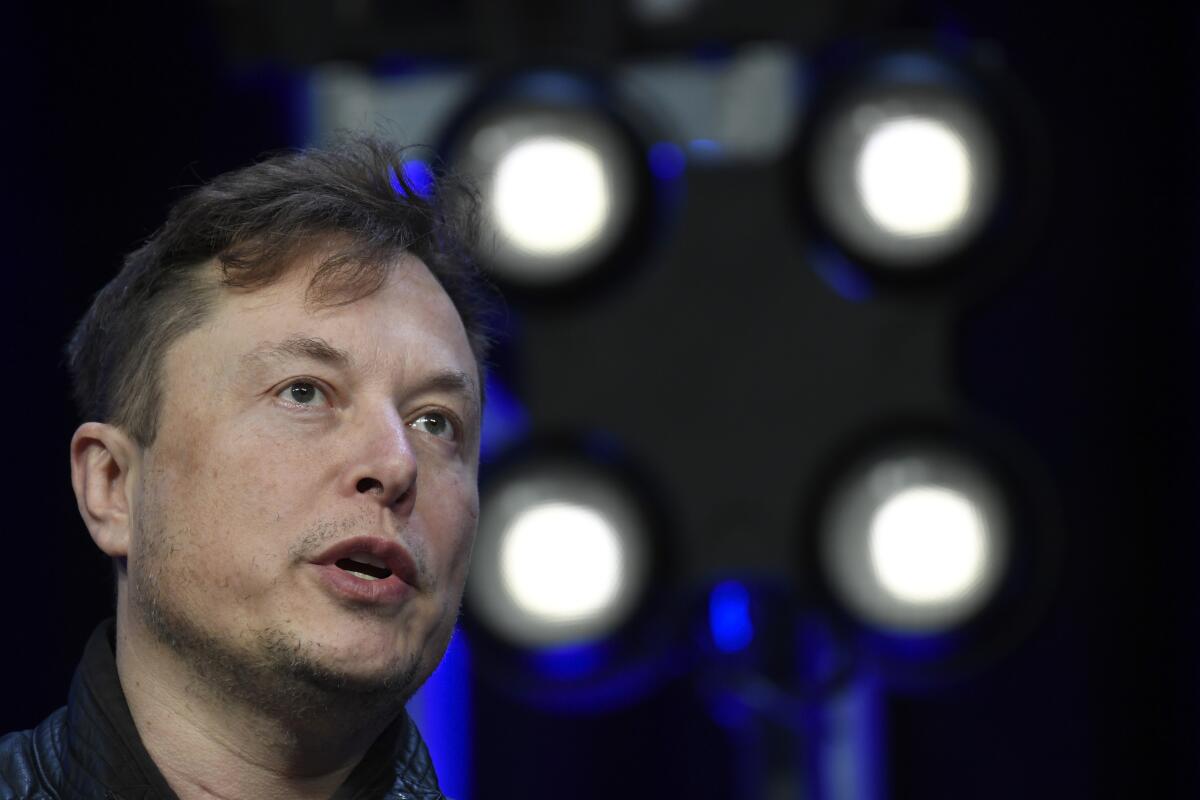

The nonprofit news organization ProPublica has just performed a significant public service by publishing federal tax records of some of America’s leading billionaires, including Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk.

The records are eye-opening, showing how the super-rich have gained from a tax system rigged in their favor. As ProPublica reports, the system allows them to pay a minuscule portion of their wealth, and sometimes their conventional income, in taxes.

It’s not their tax-avoidance methods that are so striking, for those are familiar to anyone paying attention, but the scale of tax breaks.

This is a system designed for the fortunate few by professional tax dodgers.

— Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), in 2019

Bezos’ wealth grew by $99 billion from 2014 to 2018, but he paid only about 1% of that growth in federal taxes. Musk’s fortune grew by about $14 billion in that time frame, but he paid only about 3.27% of that increase in federal taxes.

Statistics like these illustrate the adage that what’s really scandalous in American society isn’t what’s illegal, but what’s legal.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

All the tax-avoidance devices documented by ProPublica are, in fact, perfectly legal. But they’re useful chiefly for millionaires and billionaires who have the legal flexibility to sequester their wealth in categories that enjoy either low tax rates or infinitely deferrable tax liabilities.

What’s most important about the disclosures is that they point to a remedy for economic inequality that has been heard more and more often: Tax wealth, not merely income.

Wealth taxes were proposed by Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders during their presidential campaigns. Warren reintroduced her idea in Congress this year. The scale of wealth concentration in a few hands makes a wealth tax imperative.

There’s been a certain amount of sniffing that the ProPublica disclosures are old news — that the tax dodge of unrealized capital gains and other breaks available chiefly to those with a lot of money have long been known. The disclosures “told me things I already knew,” tweeted Washington Post libertarian columnist Megan McArdle.

McArdle is correct; we’ve been writing about the scandal of untaxed capital gains for years. But so what? Sometimes putting a face to a scam finally gets people’s attention sufficiently to do something about it. That’s the value of the ProPublica package.

McArdle — like the IRS itself — is also distracted by the side issue of how ProPublica got its hands on the tax returns, raising the issue of whether the leaker of private information should be prosecuted. There’s something to be said for that. Neither you nor I would probably relish our tax returns going rogue, whether or not they’re pristine.

But sometimes the value of the information trumps the manner of its disclosure. Arguably, that’s the case here.

Let’s examine what the billionaires’ returns tell us about the accumulation of wealth in this, the second Gilded Age.

Fundamentally, they demonstrate how the U.S. tax system has been rigged to favor the accumulation of wealth and its passage from generation to generation. “This is a system designed for the fortunate few by professional tax dodgers,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) wrote in 2019.

Wealthy Americans know the capital gains tax is their biggest loophole — and they won’t give it up easily.

As we’ve reported, the principal device for this is the capital gains tax.

Edward Kleinbard, the late taxation bard of USC, used to describe the capital gains tax as our only voluntary tax. It’s levied only when capital assets such as stocks, bonds or real estate are sold and the gains “realized.” Therefore, it can be deferred indefinitely simply by not selling.

But wait, there’s more: Another feature of the tax code allows wealthy families to avoid the tax permanently. That feature is the step-up in basis upon death. What that means is that when a capital asset is bequeathed to heirs, the basis — the price originally paid for the asset — is reset to its value at the owner’s death. When the owner expires, so does the tax liability.

Think of it this way: Say your father bought a share of stock for $100 (his cost basis) and over his lifetime it grew in value to $200. If he sold it while alive, he’d pay a tax on the $100 gain.

If he kept the share and willed it to you upon his death, its cost basis would be reset to $200, and you could sell it at that price tax-free. That break alone has been estimated to cost the U.S. Treasury more than $50 billion a year.

Of course, some people have to sell assets, realize their gains and pay the tax. But not, typically, billionaires like Bezos and Musk. They have the creditworthiness and expertise to capture the value of their assets without selling them. They can use the assets as collateral for loans or sell options against their holdings, for example.

ProPublica couldn’t find much about loans in the IRS documents because they’re not reportable as income, though evidence of big borrowing by the wealthy leaks into public disclosures now and then.

What’s especially insidious about the avoidance of tax on wealth by the super-rich is that much of their wealth is founded on public services paid for by taxpaying Americans.

It’s widely assumed that the biggest tax scofflaws are those with the most money. A new study tells us things are much worse than anyone suspected.

Take Bezos’ Amazon. The merchandise it sells customers is delivered over public highways funded by taxpayers or via airports funded by taxpayers. In 2007 and 2011, according to the ProPublica documents, Bezos didn’t rank as a taxpayer, since his tax bill came to zero.

Amazon has also gained from lax government policies, especially labor regulation. Labor leaders allege that the company’s exploitation of anti-union laws helped it defeat a union organizing drive at its warehouse in Bessemer, Ala., in April.

Musk also has gained from taxpayers’ indulgence. Sales of electric vehicles by Tesla Motors, which he controls, have been assisted by taxpayer-funded incentives awarded to his customers — $319.3-million total from the state of California, and an undetermined amount from the federal government, which awarded Tesla buyers up to $7,500 per car until the credit phased out Jan. 1, 2020, when Tesla sales reached the statutory limit.

Musk paid no taxes in 2018, according to ProPublica.

Both entrepreneurs have also profited handsomely from taxpayer-funded subsidies to their companies. Amazon has collected $3.2 billion in state and local tax credits, abatements, rebates and other subsidies since 2000, according to the subsidy tracker Good Jobs First. Tesla has collected $2.5 billion in state and local handouts since 2007. Good Jobs First ranks Amazon 10th and Tesla 15th in total subsidies among companies in its database.

Musk’s company SpaceX has collected $106.5 million, mostly in the form of a federal loan guarantee, since 2012, the database indicates.

Musk and Bezos have gone head to head in the race for federal subsidies for space exploration: After SpaceX beat Bezos’ Blue Origin for a $2.9-billion NASA contract for a lunar landing craft, a $10-billion appropriation to keep both companies on the federal payroll was introduced by Democratic Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington, Bezos’ corporate seat. The measure is being labeled a “Bezos bailout.”

The key question raised by billionaires’ tax avoidance is what to do about it.

Wyden has proposed reworking this system to shrink the advantage of the super-rich by eliminating the preferential tax rate for capital gains (President Biden has proposed this too) and by requiring that unrealized capital gains be taxed every year. Warren’s proposal would impose a 2% tax on the net value of stocks, bonds and anything else of value exceeding a total of $50 million, and an additional 1% on net worth above $1 billion.

When Warren first proposed such a scheme during the campaign, critics picked it apart as possibly unconstitutional. Warren’s advisors disputed that. Critics also said it would be difficult to administer — the price of publicly traded securities is easily discoverable, but what about rarely marketed assets such as art or collectibles? The IRS, however, is perfectly capable of determining the value of virtually any asset; the challenge lies in granting the agency expanded authority to do so.

Critics also pointed out that European countries that tried wealth taxes in the past eventually abandoned the idea. But that’s no surprise: In those countries, like ours, political power is wielded by the wealthy, and they had every interest in seeing that taxing their wealth wouldn’t happen.

The least disputable aspect of the excessive accumulation of wealth in America is that a solution is desperately needed.

Ed Kleinbard knew more about taxation than almost anyone and put it to work for the public interest.

The Founding Fathers saw the phenomenon as flatly undemocratic. In his autobiography, Thomas Jefferson wrote of bills he had advocated to form “a system by which every fibre would be eradicated of antient [sic] or future aristocracy; and a foundation laid for a government truly republican.” His goal was to “prevent the accumulation and perpetuation of wealth in select families.”

Jefferson would be appalled at the concentration of wealth in America today. Presumably he would find sound economic and social sense in taxing the hell out of excessive incomes and excessive wealth.

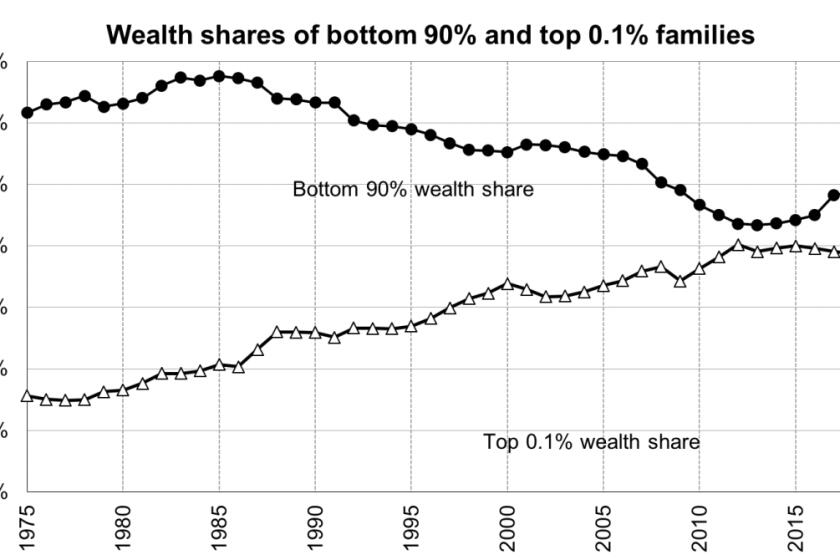

As is observed by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of UC Berkeley, who were Warren’s economic advisors, the top 0.1% today control almost as much wealth as the bottom 90%. Wealth disparity on this scale has a distinctly corrosive effect on society and democracy. As political economist Benjamin Friedman wrote in 2009, its “grave moral consequences” include “racial and religious discrimination, antipathy toward immigrants, [and] lack of generosity toward the poor” — all features of our current political landscape.

Those consequences are only growing worse. No one on Earth needs wealth on the scale of Bezos or Musk, especially as social needs are going unmet for lack of public resources, and especially given that the super-rich spend at least part of their wealth to ensure that they and their heirs can keep more of what they collected with the assistance of public services funded by other taxpayers.

Sure, whoever leaked the tax records to ProPublica should be condemned for invading the privacy of individuals. And granted our heartfelt thanks for having done so.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.