Judge orders Google to hand over anti-union strategy documents in retaliation hearing

Google will have to turn over documents outlining its anti-union strategy in response to a National Labor Relations Board complaint against the online search giant, according to an order issued Friday.

The board first filed its complaint against Google in December 2020, accusing the company of spying on employees, blocking employees from speaking with one another about work conditions and firing several employees in retaliation for attempting to unionize, all of which are illegal under federal labor law. In June of this year, the board expanded its complaint to include three more former workers who allege that the company fired them in retaliation for protesting its work with U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

At stake is a weighty question for American workers in the tech sector and beyond: Do workers have the right to protest at work?

The precedent is clear for some areas, explicitly protecting workers from retaliation for workplace organizing over traditional labor issues such as wages, hours and working conditions. But when the NLRB added to the complaint the workers who say they were fired for organizing against Google’s work with the border agency, the case’s scope grew to include the possibility that protesting the broader business decisions of an employer could be protected under labor law.

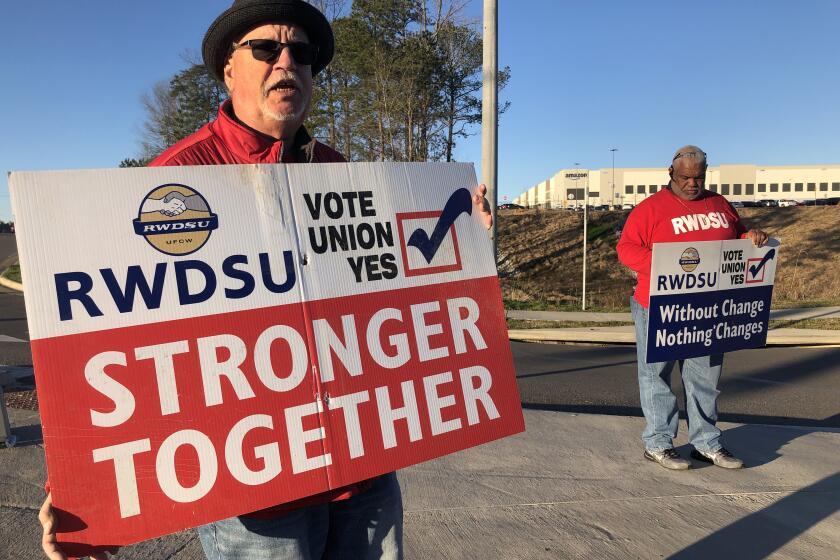

The order for a new union election for Amazon warehouse workers comes after a review of the company’s conduct during the union drive this year.

Google has said that it fired the workers in the complaint not for their workplace activism but for violating its data security policies, an allegation that the workers have denied. The company did not respond to a request for comment on the order.

The new ruling revolves around Google’s work with IRI Consultants, a labor relations firm that Google retained in 2019 to create a campaign of “antiunion messaging and message amplification strategies and training” tailored to Google’s workforce, a project code-named Project Vivian.

This year the former Google employees subpoenaed the company’s records pertaining to the campaign. Google responded by saying that it found 1,507 relevant documents, but that it would not hand them over, arguing that they were protected by attorney-client privilege.

In September, the NLRB assigned Judge Paul Bogas to serve as “special master” in the case and review the documents one by one to determine whether Google’s argument held up.

Bogas’ interim report, filed Friday, found that only nine of the 80 documents he had reviewed so far contained any information covered by attorney-client privilege, and for many documents only small sections could be redacted under that claim. He also wrote that Google “felt it necessary to attempt to conjure a privilege by detouring IRI material through outside legal counsel” — in other words, Google asked IRI to route its communications through a law firm in an attempt to keep it shielded under attorney-client privilege.

“This effort at creating the impression of legal advice is not only disingenuous, but fails under established precedent holding that a party cannot cloak otherwise unprivileged material in attorney-client privilege simply by sharing it with legal counsel,” Bogas wrote.

Google is ordered to produce the documents immediately, barring specific sections that Bogas judged worthy of redacting because of real attorney-client privilege, and Bogas will continue to review the remaining documents in coming months.

Three of the former employees involved in the case — the three who allege retaliation for protesting Google’s work with U.S. Customs and Border Protection — also filed a lawsuit Monday accusing Google of violating California law by targeting gay and trans employees for retaliation, slandering one former employee and breach of contract.

Three former Google employees are suing the company, saying its famous ‘Don’t Be Evil’ slogan required them to go public with their concerns. They also allege they were targeted for being gay or trans.

The breach of contract claim, in particular, relies on the argument that Google’s famous motto, “Don’t be evil,” was a part of the employee handbook at the time that the protests took place, and that the employees were merely following orders to speak up against unethical company behavior.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.