Jeff Crouthamel can never forget the time his father was asked to deliver a wriggling cow to a ship docked in San Pedro Harbor. The cow twisted out of the sling being used to hoist it aboard and had to be fished out of the water.

Or the shipment of 100 live chickens intended to feed a delayed ship’s crew that instead spent five days around the Crouthamel household, doing what chickens do. Crouthamel’s job was to help put up chicken wire around the family home and collect newly laid eggs from the hens, who weren’t happy about the arrangement.

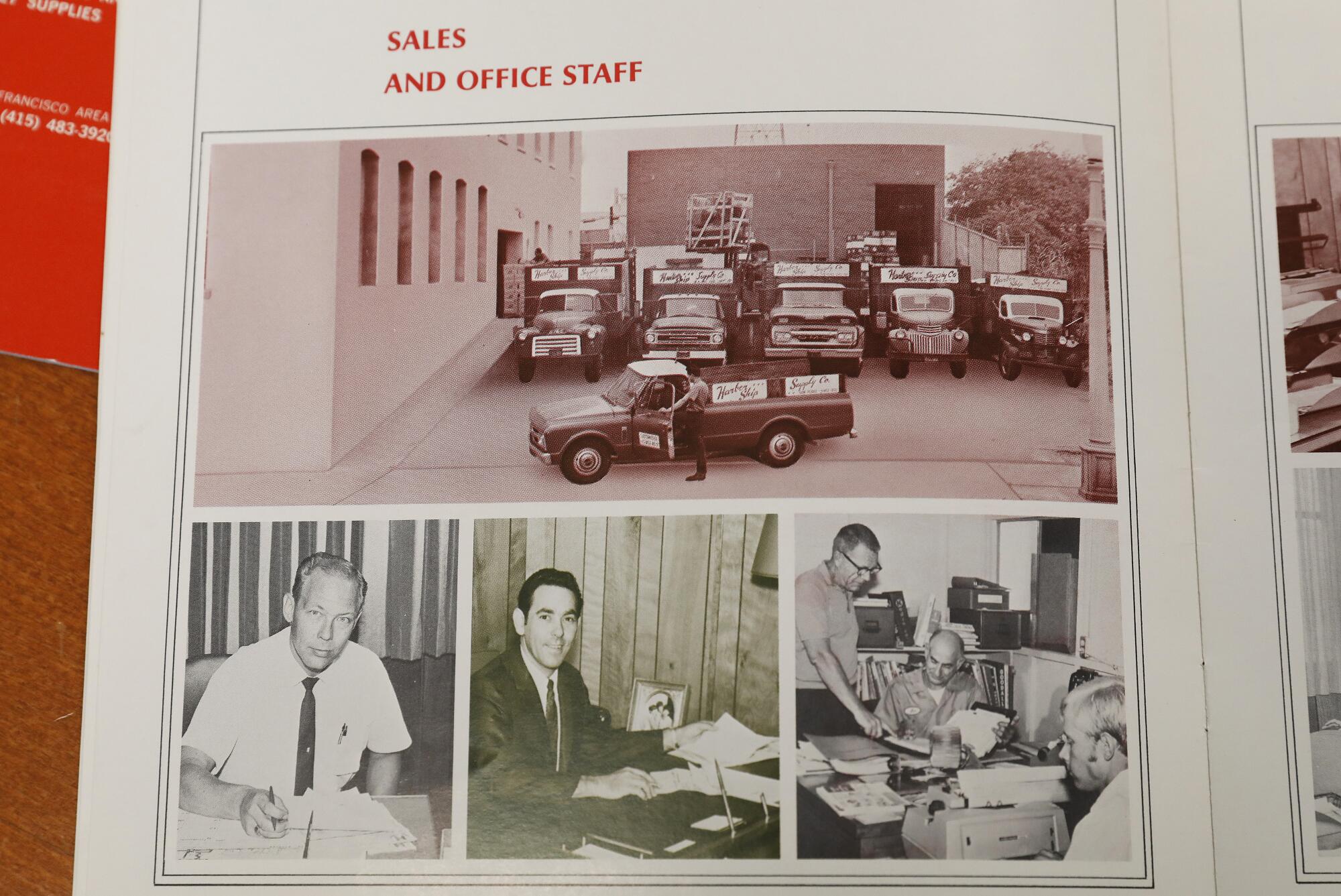

Those are pleasant memories compared with the problems currently facing Harbor Ship Supply, a small San Pedro business started by Crouthamel’s grandfather to provide goods for vessels arriving at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. The 90-year-old company now holds a dominant position in its line of work, controlling the California coast from San Diego to Oakland, with inroads as far north as Anacortes, Wash.

At 68, Crouthamel ought to be basking in that position, swimming in profits and perhaps readying to hand over the reins to one or both of his capable sons. That’s because, when ships arrive from distant ports, it’s Crouthamel’s company that is called upon to restock them with a wide variety of goods, including groceries, tools and all manner of gifts for the folks back home.

But talk to him, and it’s like a dam bursting.

“Everything is worse,” he says with the calm of a captain fully prepared to go down with his ship. “From coordinating stores and delivering to ships to actually getting product.”

At the Long Beach port, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg praised local efforts to improve supply-chain issues. But a fresh challenge looms.

Harbor Ship Supply is trying to stay afloat in unprecedented times, facing challenges that some experts say won’t ease this year. Some say the global supply chain that moves goods from raw materials to factories to consumers’ homes has been permanently altered.

“It’s bigger than a supply-chain issue. It’s an employment issue. It’s a trucking issue,” Crouthamel said. “Our operating expenses have gone up dramatically just to maintain what we’re doing.”

Logistics expert Bill Thayer said the goods-movement industry and consumers have been reeling from “once-in-a-lifetime, world-changing kind of events: The greatest supply-chain disruption since World War II, the worst pandemic since the Great Influenza of 1918. Throw in the explosive growth of global purchasing. You’ve just taken three world-changing events and added them together.”

“You’ve been comfortable with choices and availability and accessibility to everything” before the pandemic, said Thayer, chief executive of Fillogic, a New York company that operates mall-based micro-distribution hubs for retailers. “Now [you’re] being forced to choose, not to the point that you’re not going to get your food, for example, it’s just not going to be the food that you want.”

Harbor Ship Supply is among the shrinking ranks of ship chandlers, a name that derives from the French word for candles, once a key item onboard ship.

Founded in 1932, Harbor Ship Supply is the oldest ship supplier in Southern California and is part supermarket, hardware store and gift shop to ships and seafarers.

Candles aren’t in demand anymore, but over the years the company has gotten all sorts of requests, including for rockets, pig heads and chicken feet.

On a recent morning, the company’s warehouse was filled with wooden pallets of more mundane goods destined for arriving ships. Popular items include rice, sugar, flour, cleaning supplies and toilet paper.

The containership President Wilson needed two pallets of bottled drinking water. The vehicle carrier Graceful Leader had requested Brussels sprouts, mandarin oranges and other California fruits and vegetables. The crude oil tanker Emerald Spirit needed sponges and lots of cigarettes.

But acquiring those products has become harder and more expensive, Crouthamel said.

“If we need a truckload of extended life milk,” Crouthamel said, “it comes from Utah. We used to make a call, and have it that next week. Now, truckers don’t want to come to California anymore. Regulations, fuel costs or they just can’t find a driver. Now, they’re saying, ‘We can’t get a truck. We’ll let you know.’ So it could be three weeks, four weeks.”

Follow a container of board games from China to St. Louis to see all the delays it encounters along the way.

Raising prices to cover costs is difficult, he said.

“The hard part on our business is that we’re dealing with a mobile customer” — ships that come and go — “so we’re not competing against another ship supplier here in town, we’re competing against other countries and other ports,” Crouthamel said. “So if they can’t get it in L.A., they say, ‘We’re waiting until we get back to China,’ So when they’re not happy with the cost of the product, they’ll just keep postponing as long as they can.”

“These companies are stuck taking a major hit to their bottom line while trying to stay in business,” said Nick Vyas, executive director of USC’s Kendrick Global Supply Chain Institute. “The continuous pressure from COVID coupled with our supply-chain issues at home, in terms of low labor participation, shortage of inventory and not having enough people to support the operation. There’s tremendous pressure on the cost side with customers who aren’t willing to absorb the increases.”

Crouthamel says his 41-employee company was on pace to post $21 million in revenues last year, but instead of the 30% margin on his sales his dominant place in the market should demand, he’s settling for half that. “That’s why so few want to do this work, because of the amount of work involved for such a low margin,” he said.

To cope with the changes, Crouthamel said he has diversified where he gets his products because his traditional sources are having trouble filling orders.

“Before, we had a limited number of suppliers we knew that we could trust,” Crouthamel said. “Now we have to have A, B, C and D lists of suppliers we can turn to because we are being shorted on so many orders. We’re having to run out to local markets a lot now too, for example, to pick up two cases of Coca-Cola because they shorted our order because they didn’t have enough aluminum for the cans. We’ve had to adjust and be a lot more flexible.”

When Harbor Ship Supply opened its doors, ships stayed in port much longer and there were few tight delivery deadlines. The ships lacked refrigeration and required large amounts of easily found items such as coal and ice. Live animal deliveries were common, including the cow that went for a swim.

The most unusual aspect now includes trips that seafarers used to be able to make on their own, before pandemic precautions forced them to stay on their ships.

That has included treks to Best Buy for electronics and Victoria’s Secret for dozens of bottles of perfumes and lotions. On rare occasions, seafarers give in to their attachment to American fast food, necessitating trips to Domino’s Pizza, In-N-Out Burger and McDonalds, among others.

“You name it, we’ve delivered it,” he said.

Crouthamel said he stays in the business “because it’s in my blood, from my grandfather Charles and father Harold before me.”

“If you don’t have a personal stake in this business,” he said, “you’re never going to work hard enough to make it work.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.