Retired carpenter Joe Braus of Burbank spends about $200 a week on groceries, an amount he notices is rising fast.

But that hasn’t stopped him from shopping at Whole Foods Market in Burbank with his partner or making extra trips to specialty stores such as Sprouts Farmers Market and Trader Joe’s to find healthy alternatives, including grass-fed beef and free-range chicken.

“This is the way we eat,” said Braus, 72. “We eat natural. We eat organic and if it costs more we pay it.”

We are all paying for it, whether we eat healthy or not. Across the country, grocery prices have shot up 11.9% over the last 12 months — 10.9% in the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim region — with the biggest jumps in meats, poultry, fish, eggs and vegetables, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Experts blame supply chain headaches, high fuel and labor costs, a new strain of avian flu that has led to the deaths of millions of chickens, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the persistent drought in California for contributing to the price increases.

“This is the worst price inflation since President Nixon was in office,” said Burt P. Flickinger III, managing director of retail consulting firm Strategic Resource Group.

Southern California is the nation’s largest and most competitive market for the grocery industry, with $48.6 billion in annual sales. That means shoppers have lots of options, and the potential for big savings. But prices fluctuate daily — sometimes hourly — and with many of us choosing stores that are near our homes or workplaces, it can be hard to know how prices at our local grocery store compare with the many others out there.

“Everyone has their ecosystem of where they shop and how they shop,” said Michael Swanson, Wells Fargo’s chief agricultural economist.

The Times set out to survey prices of common grocery items at 10 grocery chains in the Los Angeles area on the same day, to offer a snapshot of a typical, basic grocery haul and explain the factors behind grocery pricing.

Reporters visited 10 grocery stores in the L.A. area on Monday, June 20, and recorded the prices of 15 items.

We checked prices at the 10 most-visited grocery store chains in the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim region, as measured by foot traffic tracked through anonymous cellphone data compiled by Placer.ai, a location analytics company based in California.

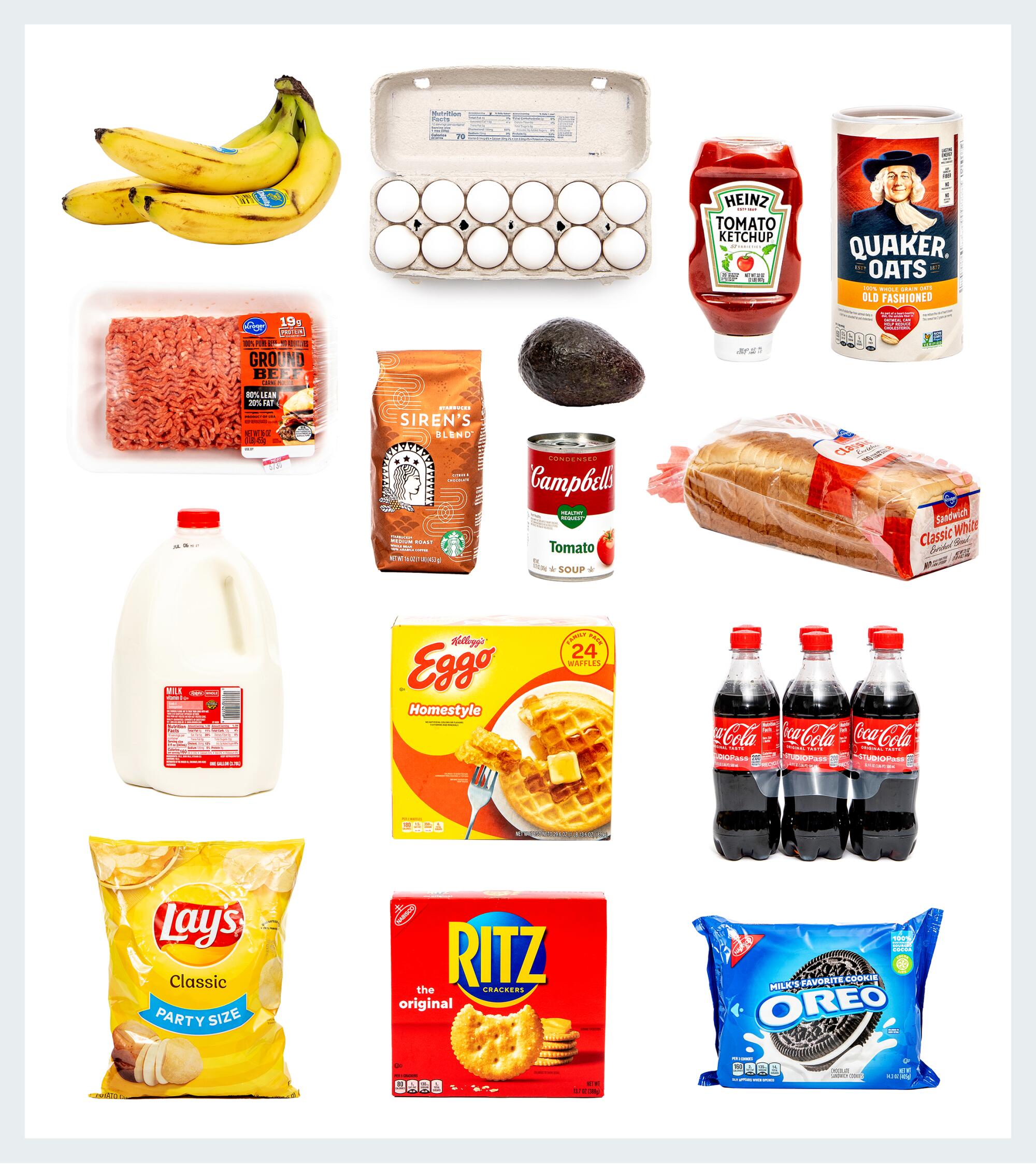

The 15 foods we price-checked include 10 of the most popular grocery items nationally, according to consumer surveys by YouGov and Trader Joe’s. We added several items to reflect Southern California tastes, such as avocados, coffee and bananas.

Because the survey was limited and not scientific, little can be deduced from the data on how prices are moving as inflation continues to tear through everyday life. By comparison, the Bureau of Labor Statistics determines the consumer price index, the measure of inflation commonly cited, by comparing the prices of more than 32,000 food items. (See our note on methodology at the end of this story.)

Try these tips for saving on groceries as prices soar.

How prices differed

Still, some broad patterns were apparent.

Industry experts said the prices at same-name stores should be roughly the same across different locations. For example, a pound of bananas at Ralphs in Los Feliz should be priced the same as at a Ralphs in Pasadena.

We found that prices of staples such as milk and eggs can vary widely between competing grocery stores. Prices can even vary between grocery chains that are owned by the same company.

Kroger Co. owns Ralphs and Food4Less but the same item sold at the two chains — an 18-ounce container of Quaker Oats, for example — differed by 38%, according to the data Times reporters collected.

With grocery prices up nearly 11% in the past 12 months in the Los Angeles area, The Times is researching the best ways to save. Please share your tips in our form.

A gallon of whole milk can range in price from $3.59 to $4.99, depending on where you shop. A loaf of white bread sells for as little as $1.49 and as much as $3.99. A dozen large eggs can sell for $2.49 at one store and $3.99 at another. Buy all 15 items and you can spend as much as $79.65 or as little as $48.88, based on the grocery store.

Here are the price tallies for the 15 items on our list:

- Trader Joe’s: $48.88

- Food4Less: $59.14

- Stater Bros.: $61.64

- Smart & Final: $66.12

- Whole Foods: $67.45

- Albertsons: $69.62

- Ralphs: $70.08

- Northgate Market: $70.97

- Vons: $73.02

- Sprouts: $79.65

Why the disparity? The largest chains — such as Walmart and Kroger— have tremendous bargaining leverage to negotiate lower prices with producers and suppliers.

On the other hand, specialty markets such as Whole Foods and Sprouts may charge a premium price for staples such as bread, fruits and vegetables that are promoted as fresher and more nutritious than those sold in rival stores.

“We are actually trying to be measured on how we do pricing,” said Neil Stern, the chief executive of Good Food Holdings, the company that operates Bristol Farms, Lazy Acres Natural Market, Metropolitan Market, New Seasons Market and New Leaf Community Markets.

Tall cans of AriZona iced tea have cost 99 cents since 1992. The family behind the company says it’s committed to that price even as the prices of aluminum and corn syrup climb higher.

A representative for Trader Joe’s did not respond to a request for comment, but the grocery chain says on its website that it keeps prices low by buying in bulk and directly from suppliers whenever possible and does not charge suppliers what is called a “slotting fee” to keep items on the shelf, which results in higher prices.

Also at play is the strategy of individual grocery chains. Many are willing to absorb up to half of the price hikes on their most popular items — dubbed “known value items,” such as milk, eggs and bread — to keep loyal shoppers returning. Over the last several months, the producer price index, which measures the cost of producing goods and offering services, has risen several percentage points faster than the consumer price index, which measures what shoppers pay for those products and services.

With profit margins typically under 2%, grocers must be judicious when deciding how much of the rising costs to absorb, how much to pass on to consumers and which grocery prices they can boost without losing loyal customers. The average grocery store offers 31,000 different items, giving grocers lots of pricing options.

Often grocers set prices primarily to match those of rival supermarkets, said Rick Phegley, executive vice president at Smart & Final.

Residents of the Los Angeles area are changing how they eat, shop and do business to cope with some of the nation’s highest gas and housing prices.

“We are always paying attention to what competitors are pricing products when we sell the same products,” he said, adding that a supermarket chain can keep prices low during an inflation surge only by cutting into its narrow profit margin.

Representatives for Ralphs, Trader Joe’s, Vons, Food4Less, Stater Bros., Albertsons, Whole Foods, Sprouts and Northgate did not respond to requests for comment.

Grocery stores will often sell a handful of popular items at a price so low that it makes them no profit — known as “loss leaders” — to attract shoppers in the hopes they will then spend heavily on other items, resulting in a profitable visit overall. This strategy is common before the Thanksgiving holiday with the sale of turkeys or around the Fourth of July with the sale of hot dogs.

But no matter how careful grocers are at trying to blunt the pain of inflation, some shoppers have begun to put cost savings ahead of store loyalty.

Julieta Miguel, 43, lives in Montebello but was recently shopping at a Food4Less in Pico-Union to get lower prices on tangerines, Oreo and Chips Ahoy cookies, Cheez-It crackers and mayonnaise.

Vons is the closest supermarket to Miguel’s home, but she said the prices there are more expensive so she goes only when she really needs an item or two. Instead, Miguel prefers Ralphs and Food 4 Less for her twice-a-week grocery trips.

Miguel, a mental health case manager, began noticing the uptick in prices at the beginning of the year. “It’s probably 10% more for each item,” she said, which has pushed her average grocery bill to more than $200. With summer vacation here, she worries that her food spending will rise as her three children spend more time at home.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Shifting habits

When prices began to surge in March and April, shoppers in Southern California started to visit low-price grocery chains such as Food4Less and Smart & Final more often, and to shop less often at specialty stores such as Trader Joe’s and Sprouts, according to Placer.ai.

But within a few months, shopping patterns at most grocery store chains returned to previous levels, Placer.ai’s data showed.

Low-income shoppers are more likely to change their shopping habits, such as switching from fresh to frozen meats, according to an April study by the Food Industry Assn., a trade group representing grocers and producers. More than one-third of shoppers said they turn more often to store brand items rather than well-known national brands, the study found.

John Kalish, a Los Feliz resident and TV producer who shops at Trader Joe’s, found the recent jump in prices hard to miss.

“I’m pretty careful with my budget, but I’ve noticed that the totals have gone from the $40s to the $70s,” he said. To make up for the difference, Kalish changed a key shopping habit: “I buy cheaper wine.”

The good news is that price hikes in the past have almost always been followed quickly by price drops, thanks to improved efficiencies, such as automation, and competition among producers, said Swanson, the agriculture economist.

One of the biggest factors in the recent rise in prices was labor shortages, which Swanson said are easing, with a hiring surge for truck drivers and food factory employees.

The state’s minimum wage for large employers is currently $15 an hour, with employers that have fewer than 26 workers paying $14 an hour.

“The market is responding,” he said.

And shoppers who adjusted their buying habits may not go back to their old ways.

Consumers who switched from national brands to a grocery store’s private label brand — also known as generic brands — may continue to buy private label items, realizing that they are often equal in quality and much cheaper, Swanson said.

“A lot of branded food markets may suffer some erosion from this shopping experience,” he said.

Times staff writers Andrea Chang, Laurence Darmiento, Sam Dean, Jack Flemming, Somesh Jha, Andrew Khouri, Suhauna Hussain, Nour Malas and Ronald D. White contributed to this report.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

About this story

For example, Vons, Ralphs, Food4Less and Stater Bros. all sell Eggo Waffles in a 24-unit box. Trader Joe’s sells an eight-unit box of multigrain toaster waffles. We multiplied the price of the Trader Joe’s waffles by three to match it up with the Eggo Waffles price. Similar adjustments were made to calculate prices for other products. We performed the same price checks on a Monday two weeks earlier, to see whether prices changed in that window and to account for sales, discounts and other price anomalies. Prices broadly remained unchanged.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.