Who’s sending mystery Uber Eats orders to L.A. neighborhoods? The plot thickens

Separated by about 16 miles of traffic-snarled L.A. roads — and an income bracket or two — Westwood Hills and Highland Park may not seem to have a lot in common.

But earlier this year, the neighborhoods were bound by a strange phenomenon: Days and days of unwanted food deliveries from Uber Eats.

In Highland Park, the errant orders were mostly met with bemusement, as The Times previously reported. But in Westwood Hills, an affluent neighborhood nestled between the UCLA campus and the 405 Freeway, the free McNuggets were hardly just free McNuggets.

As deliveries from McDonald’s, Starbucks and other restaurants piled up on people’s doorsteps in late January, Terry Tegnazian, a member of the board of the Westwood Hills Property Owners Assn., began hearing from worried neighbors, including one man who thought there could be “something nefarious and criminal going on.”

The resident, Tegnazian said, wondered whether the orders, which were paid for and in the names of other people, were being sent “as a way of casing houses, to see if anybody was home for a possible burglary.”

For more than two weeks, residents on a street in Highland Park have received unsolicited Uber Eats deliveries from McDonald’s and Starbucks, creating a confusing whodunit.

The theory spread quickly, sparking alarm and leading the homeowners group to report the matter to the Los Angeles Police Department. A Westwood Hills resident who asked that her name not be disclosed over privacy concerns called the dozens of unwanted orders that she received “creepy and unnerving.”

“It felt invasive because there was a revolving door of strangers dropping off food,” she said. “But is that what they were really doing?”

In the end, though, no burglaries were tied to the deliveries, which predated the similar spate in Highland Park. Westwood Hills residents were told by Tegnazian in a Feb. 9 message on their private email network that the LAPD had “concluded that all these deliveries are not initiated by a burglary ring.” The LAPD did not respond to questions about its interaction with the homeowners group.

A spokesperson for Uber, the parent of Uber Eats, told The Times that the San Francisco company had been in contact with the LAPD, and there was no indication the unwanted deliveries were directly tied to any residential burglaries. The Uber representative said the company had banned some accounts from the platform and taken other unspecified steps to prevent misuse of the service.

“The reports of unsolicited deliveries are concerning,” the Uber spokesperson said in a statement. “We ... will not hesitate to take additional action if the unsolicited orders continue.”

For some of the armchair detectives in Westwood Hills and Highland Park who’ve concocted elaborate theories to explain the avalanche of unwanted food, the burglary-ring hypothesis seemed to be out, and it was back to the drawing board. But there was no shortage of fresh conjecture. Among the explanations floated were those focused on the deliveries being the product of a university psychology experiment, a GPS glitch, a marketing ploy or a phishing scheme targeting drivers.

Although getting to the bottom of the Uber Eats mystery may seem unimportant — especially given everything else that is going on in the world — the fact that the stakes are so low may be what makes it such an irresistible topic of speculation. This is, after all, a whodunit that’s centered on free food. It’s “mostly something that’s not terrifying,” said sociologist Malka Older, author of the science fiction novel “Infomocracy.”

“Somebody is doing something, and it’s hard to explain,” said Older, a faculty associate at Arizona State University. “That’s why we read mystery novels. Some kind of plot has happened. There is something going on here that’s worth something in either money or satisfaction. That makes us curious.”

Tall cans of AriZona iced tea have cost 99 cents since 1992. The family behind the company says it’s committed to that price even as the prices of aluminum and corn syrup climb higher.

Good mysteries make good neighbors

The Westwood Hills deliveries had stopped by mid-February. And residents in Highland Park, where the unwanted orders began arriving in late February, said they had received none since The Times wrote about that community’s ordeal March 15.

Unlike in Westwood Hills, residents on Range View Avenue in Highland Park — a hip neighborhood popular among creative types — mostly seemed puzzled by the deliveries. And if they wanted to sample a free Shamrock shake or two, well, why not?

It’s a difference noted by Range View resident Will Neal, who said he’d received about 40 of the Uber Eats deliveries.

“Westwood was entirely sure it was people trying to seek out their houses to burglarize them,” said Neal, a documentary film editor. “My neighborhood came to the near consensus that it was some sort of weird promotion for these [food] companies.”

Older was also struck by the differing reactions.

“The fundamental thing is ... do we feel threatened by anything unknown?” she asked. “There are the people who are kind of trained [to say], ‘Yeah, of course they are going to try to come get our stuff.’ And the people who [say], ‘Our stuff isn’t that great — it’s fine — why would someone want it badly?’ ”

Older also emphasized a positive that had come out of the situation for both Highland Park and Westwood Hills: the strengthening of neighborly bonds, one unwanted McDonald’s McCrispy at a time.

Indeed, a resident in Highland Park previously told The Times that she and neighbors had pondered “doing a little podcast” about the episode. In Westwood Hills, meanwhile, there was a vigorous discussion about the Uber Eats deliveries on the private email network. And neighbors also looked out for one another. Tegnazian said some residents would remove deliveries from the doorsteps of people they knew to be out of town so that the food wouldn’t pile up and point to the fact that those houses were unoccupied.

“You had people receiving this who were actually forming community around it because they were talking to each other about it,” Older said.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The author couldn’t help riffing on the mystery. She joked that she could imagine the saga as the subject of a procedural TV drama. “I can also picture a cold open to one of those shows ... it seems silly and then there’s a body in your McCrispy,” she said.

An intriguing theory

Even though the deliveries stopped in both Westwood Hills and Highland Park, a new theory attempting to explain them has emerged in recent days. It centers on a fairly well-known phishing scam affecting Uber Eats drivers — one that’s been the subject of several news reports.

Here’s how it typically plays out, according to a handful of gig workers interviewed by The Times: First, a courier receives notice of an incoming order via Uber Eats’ mobile app. After picking up the food from an eatery, he or she will get a message from the customer canceling the delivery. Then the courier gets a call from someone purporting to be a representative of Uber Eats, who claims to need the driver’s login credentials to process a credit for the canceled order. With those details in hand, the scammer drains the funds from the courier’s Uber Eats account.

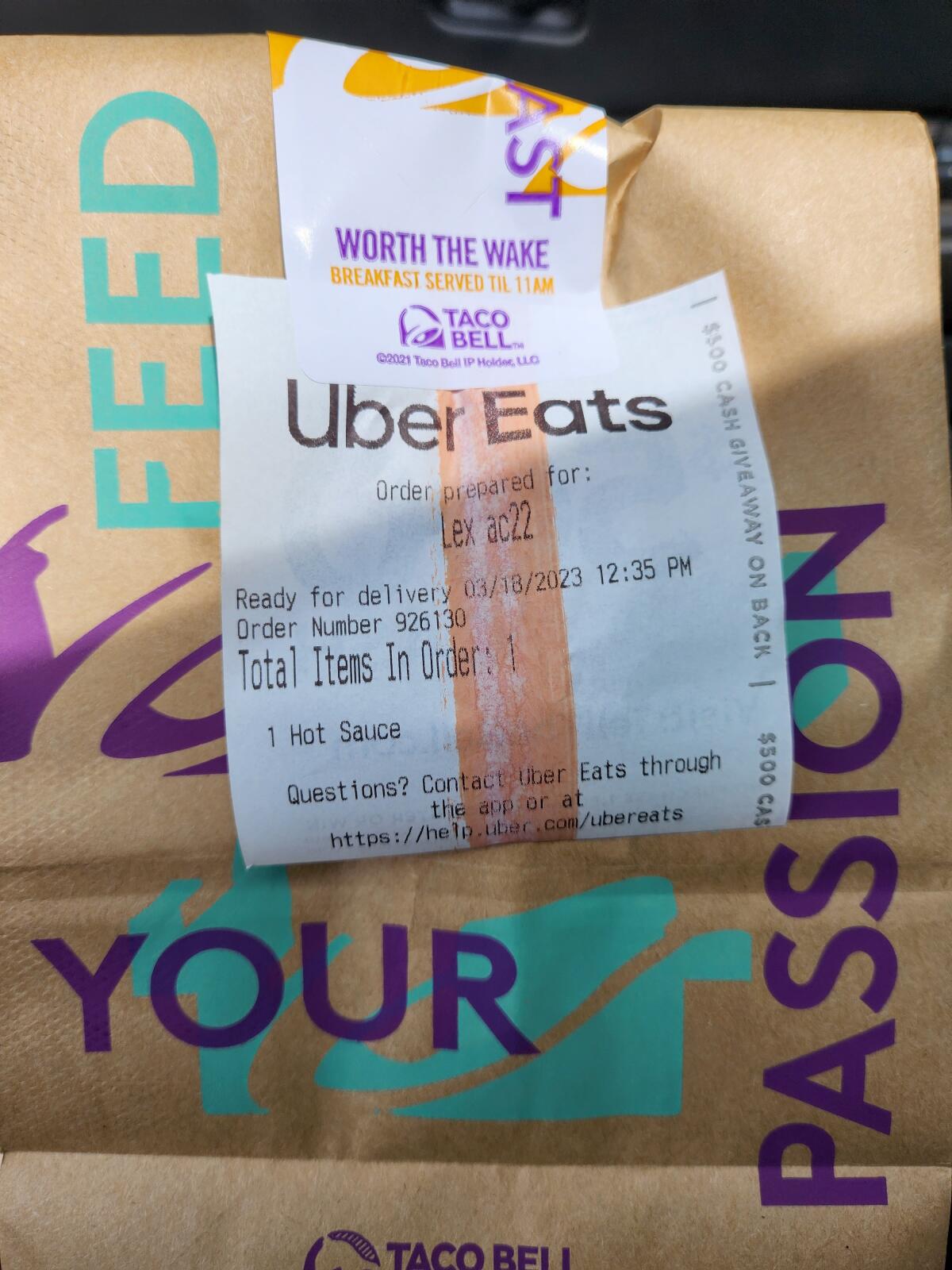

Uber Eats driver Guner Harris, 21, said he experienced a version of the scam March 18 after agreeing to deliver food from a Taco Bell location in Clermont, Fla. He said that the order he retrieved from the restaurant immediately drew his suspicion: It contained one hot sauce packet — and nothing else.

Once the customer canceled the delivery, Harris said, he got a call on his mobile phone, which displayed “Uber” as the caller. When the person requested Harris’ Uber Eats username and password to issue compensation, he refused, hung up and reported the incident to the company.

“They said it was a scam — that they’ve gotten reports of people pretending to be Uber support,” Harris said, adding that he believes the errant deliveries in L.A. bear the hallmarks of the sort of scheme he deflected.

Uber’s spokesperson said that the company had not seen activity in its system that indicated a phishing scam was connected to the unsolicited deliveries in Highland Park and Westwood Hills. The company representative also noted that it educates couriers about best practices to avoid phishing attempts, including the use of two-factor authentication for logging into its system.

LAPD Capt. Kelly Muniz said that the department did not “have anything connecting” the unwanted deliveries in L.A. to a phishing scam “as of now.”

Several recent media reports have detailed versions of the canceled-order phishing scheme. A story published by Marketwatch in July called it one of “the most common scams” affecting food delivery personnel. The article described the ordeal of an Uber Eats courier in New Mexico who lost more than $300 to a scammer. Since 2021, similar stories have been published by Santa Clarita’s KHTS FM 98.1 radio station and KNBC-TV Channel 4, among others. Some of the reports have focused on drivers for Postmates, which was acquired by Uber in 2020.

“It is just wrong to do this to drivers — some of us are working 60, 70, 80 hours a week,” said Nicole Moore, a Lyft driver and president of Rideshare Drivers United, a labor advocacy group for Uber and Lyft drivers. “The scamming is ridiculous; it is horrible. You’re not stealing from people who can afford it.”

Letting it go

Over in Westwood Hills, homeowners might be better insulated from such economic woes — but that didn’t make them any less wary.

At one point, Tegnazian said, she had asked the LAPD officer who liaises with Westwood Hills if the issue of the unwanted Uber Eats deliveries needed to be escalated.

“I asked him if we should contact the FBI for a possible cybercrime,” she said.

Soon, though, the deliveries stopped coming.

It has been more than six weeks since Westwood Hills was plagued by the errant orders. The specter of criminality no longer looms over the leafy community. Residents, Tegnazian said, seem to have mostly set aside worries that they were the target of an unlawful scheme.

“We just let it go,” she said.

Times staff writers Suhauna Hussain and Richard Winton contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.