The LIV Golf-PGA Tour merger shows why sports is so good for image washing

- Share via

Sometimes sports isn’t just about sports.

For decades, athletic events have been used to launder images and reputations in a tactic called “sportswashing.” Whether embraced by a company or a nation with regressive policies, sportswashing has particular allure, experts say, because it works.

That’s what critics say is happening with the proposed merger between the Saudi-backed LIV Golf and PGA Tour.

The deal ends a bitter war with PGA Tour, turns LIV Golf into a major force in the sports world and furthers Saudi Arabia’s efforts to expand the kingdom’s revenue beyond its shrinking oil business. But the Saudis also are banking on the glamour of athletics to outshine concerns about a history of human rights abuses.

“The merger really places the Saudi government in a very unprecedented position of influence and control over the top levels of golf,” said Joey Shea, Saudi Arabia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Given the country’s egregious human rights record, it’s particularly concerning.”

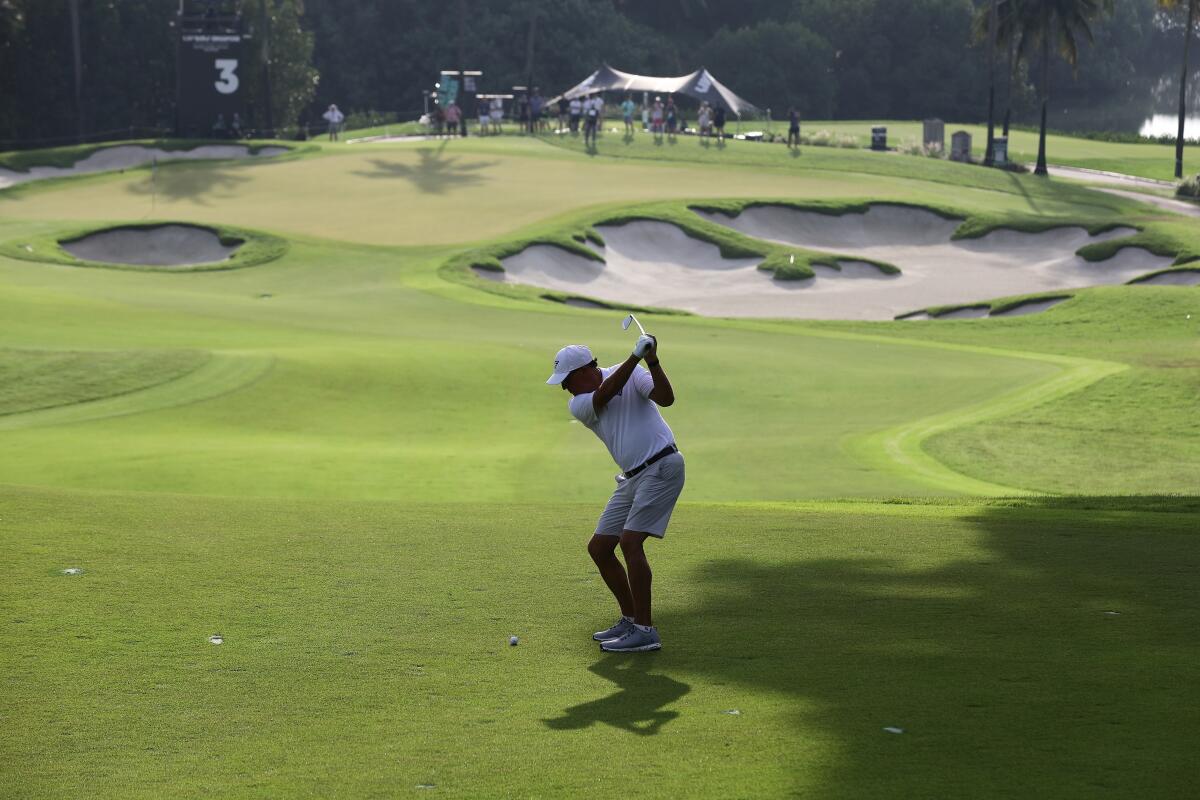

Leaders of the PGA Tour and Saudi-backed LIV Golf have been locked in a fight over the future of golf. On Tuesday, they announced a shocking merger.

Governments and companies over the years have found that using sporting events — sponsoring a team or tour, for instance, or going all out and hosting the World Cup or the Olympics — is a particularly effective tool to paint themselves in a more flattering light while also potentially enriching their coffers through lucrative broadcast rights deals and other spending.

“Sport reaches more and different people than other communication tools,” said Steve Cockburn, head of economic and social justice at Amnesty International. “A lot of people feel very deeply and connect deeply with sports.”

Using sports to launder a government’s image has several historical precedents. Hitler used the 1936 Olympics to build support for Nazi Germany, while Mussolini saw Italy’s 1938 World Cup win as a way to galvanize support for his fascist regime.

More recently, human rights activists raised concerns about China hosting the 2008 and 2022 Olympics, despite human rights abuses against the Uyghur people in Xinjiang, or Russia hosting the 2014 Sochi Olympics after the country passed anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Qatar’s hosting of the 2022 World Cup brought similar image-scrubbing complaints.

“Sports in general is a very galvanizing event or cultural phenomenon. It brings people together,” said Yoav Dubinsky, instructor of sports business at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business. “Sports events are the most watched telecasts on television. TV rights are the main source of revenue for professional sports because of their popularity, which means that the eyes of the world and the eyes of fans are on the sports.

“As a byproduct, the countries or cities or states try to capitalize on that attention to show the aspects of the countries that they want to showcase.”

After the PGA Tour and LIV Golf announced their merger, Donald Trump, Phil Mickelson and others shared their reactions. Tiger Woods hasn’t commented.

Unlike other types of image laundering — environmental greenwashing, for instance — sportswashing taps into the deep emotional ties many fans have to their teams or sports. Some of them are former athletes. Others want to feel good about who they’re cheering for and what they’re spending their time on.

“There is an elasticity when it comes to sports fandoms” that makes enthusiasts more forgiving, said Jane McManus, executive director of the Center for Sports Media at Seton Hall University. “You find a way to create a clarity in your own mind about what you’re able to cheer for and, oftentimes ... you’re not as concerned about this particular issue.”

For governments, the investment in leagues or individual teams, such as the Saudi Public Investment Fund’s purchase of Newcastle United, is negligible, experts said. The increased foray into sports is a show of strength and diplomacy, a use of soft power.

“These are trophy investments,” Cockburn said. “What they’re gaining is a huge cultural investment, loyalty from certain groups of the population and loyalty from politicians who don’t want to see that investment go away.”

Getting more involved in sports can be a double-edged sword for countries with a record of human rights violations. More involvement can lead to more scrutiny of their past record on human rights, but at the same time, it can also allow for more opportunity to showcase desirable parts of a regime.

The PGA Tour has essentially let Saudi Arabia, known for human rights violations, buy professional golf competition, columnist Bill Plaschke writes.

“The collaboration with the PGA now gives the Saudis a kosher stamp as a legitimate business partner in the U.S.,” said Dubinsky of the University of Oregon.

It’s unclear whether Saudi Arabia’s increased presence in golf will allow the country to remake its image. In a poll conducted last year by Seton Hall University, 43% of “general population” respondents said the Saudi-backed LIV Golf looked like “sportswashing,” with that percentage increasing to 52% among “avid fans.”

“You’ve seen a lot of resistance to LIV Golf among the fan base,” McManus of Seton Hall said. “I don’t know which values are going to play out more: the value of tradition or the value of money.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.