- Share via

The Cheesecake Factory’s official taste tester leaned toward a massive mound of steaming, parsley-flecked rice and jabbed his fork into a chunk of glistening cashew chicken.

He closed his eyes for a moment, considering the texture of the dish, a longtime staple that, after a couple-year hiatus, would soon return to the chain’s menu.

“Not as soft as I’d like it,” he told the executive chef, who nodded.

Next, he turned to the seared ahi tuna salad, but he doesn’t like fish, so he took a single bite of lettuce and radish before confidently setting down his fork.

“Nicely dressed. Great crunch!”

Third up was Cajun salmon with mashed potatoes and corn. He dredged a spoonful of potatoes through the sauce and his lips wiggled from side to side. He nodded twice.

“OK, delicious.”

In the 46 years since he opened the first Cheesecake Factory restaurant in Beverly Hills and grew it into the behemoth of casual dining with locations across the globe, David Overton — the company’s official taster, but also its chief executive and co-founder — has built a deep trust in the profitability of his own palate.

Overton has tasted and approved every one of the menu’s more than 250 items, which despite the factory in its name, the company likes to emphasize are prepared from scratch on site or at the company’s two bakeries.

“What I like, millions of people like,” Overton, 77, said on a recent morning at the company’s Calabasas Hills headquarters as he weighed in on new offerings. “I have the taste buds of the common man.”

Over the last few decades, as Cheesecake Factory locations popped up at malls and suburban plazas, they brought to each new corner of the country a sense that you were now in on some universal slice of Americana — a slice, it turns out, that provokes impressively fierce reactions.

It didn’t matter if you were in Tucson, Tampa or Tulsa, you, too, could now laugh with family and friends as you collectively gorged yourselves on the chain’s iconic brown bread. Before long, you, too, would come to associate the restaurant’s decor — a mashup of Egyptian-style columns, dark-wood wainscoting and ethereal murals that, when combined, exude the same over-the-top-yet-somehow-appealing vibe as a Vegas casino — with a sense of nostalgia. This would become the backdrop of birthdays and graduations and late-night meals after prom.

You were now part of the collective experience shared by doctor and author Atul Gawande, who penned a sprawling ode to the Cheesecake Factory in the New Yorker, a Los Angeles Times food columnist, who, in a viral review in 2019, called his love of the chain “irrational and possibly pathological,” and rapper Drake, who sings about his love for the Cheesecake Factory, christening it as “a place for families that drive Camrys and go to Disney.”

But not all of the attention is fawning.

The chain made national headlines in 2017, when a man detonated a homemade explosive device inside a Cheesecake Factory in Pasadena. The FBI said the case remains unsolved.

The norms around whom, and how much, Americans tip have shifted in recent years — and consumers are increasingly confused.

Late last year, a video went viral on TikTok of a woman refusing to get out of the car during a first date.

“This is the Cheesecake Factory,” she says, filming herself, in what some viewers suggested was a staged scene.

“What’s the problem with that?” he asks.

“This is a chain restaurant.”

“I literally met my husband at the bar of a Cheesecake factory 10 years ago,” Rachelle Tomlinson tweeted. “Stop all the slander!”

Before long, someone compiled a list, which also circulated on social media, of places women should refuse to go on first dates, listing Cheesecake Factory as No. 1. (No. 2, Applebee’s; No. 15, the gym; No. 16, church.) The discourse swept the internet, earning two separate pieces in the Washington Post, and loyal fans soon swarmed to the brand’s defense on X.

“WHO THE HELL DOES NOT WANNA GO TO THE CHEESECAKE FACTORY? BRO IF I WAS TAKEN THERE I WOULD PROPOSE,” one person posted on X (formerly Twitter).

The first Cheesecake Factory restaurant opened in Beverly Hills in 1978 and now has over 200 locations. With everything from Tex-Mex eggrolls to Thai lettuce wraps, it captures the essence of America — the good and the bad — in one over-the-top dining experience.

“I literally met my husband at the bar of a Cheesecake Factory 10 years ago,” Rachelle Tomlinson tweeted. “Stop all the slander!”

Tomlinson, 30, was on a girls trip to Honolulu in 2014 when she visited the chain for the first time. Tomlinson recounted in an interview how she can still visualize the moment the double doors opened and she locked into a gaze with a man with hazel eyes.

“Legit love at first sight,” her husband, Sam, recalled, saying the other thing he remembers from that night is that he drank a bunch of Mai Tais.

Exactly a year from their Cheesecake meet cute, they got married.

Growing up in Detroit, Overton said, his family could afford to eat out only once a week, usually Sundays at a deli or Chinese spot.

His father worked at a department store and his mother sold cheesecakes she baked in the family’s basement based on a recipe found in a newspaper. Back then, there were only two varieties — original and original with strawberry topping — and Overton said he and his sister earned a penny for every bakery box they helped their mother fold.

Years later, when Overton was in his 20s and chasing dreams of becoming a rock ’n’ roll drummer in San Francisco, his parents, Evelyn and Oscar, tired of Detroit and a string of business ventures that never took off, decided to move west.

They opened a small, wholesale bakery in North Hollywood, expanding their cheesecake options to include several more flavors, but the Cheesecake Factory Bakery floundered. They were in their mid-50s, working long hours and struggling to find customers who would buy in bulk.

“I was really getting tired of all these restaurateurs that wouldn’t buy the cake,” Overton said, recalling the frustration that inspired him to start a restaurant of their own.

On the day they opened in Beverly Hills in 1978, they began welcoming patrons at 2 p.m. and, by 2:10 p.m., Overton said, they were so busy that people had to wait to be seated — an immediate rush he attributes to divine intervention.

“God was really watching over us,” he said. “I like to say that we had a line in 10 minutes, and it’s really never stopped for the last 45 years.”

The company opened its second location in Marina del Rey in the early ’80s and, in 1991, opened the first out-of-state location in Washington, D.C. The next year, the company went public — ticker symbol: CAKE — and today has more than 200 locations in the U.S., as well as several in the Middle East, Mexico and Asia.

“The brand has really found a spot in the hearts of consumers.”

— Joshua Long, managing director, Stephens financial services firm

Cheesecake Factory locations brought in $2.5 billion of the company’s $3.3 billion in revenue in 2022, an average of about $12 million in sales at each restaurant, according to the company’s latest annual report to shareholders. (The company also owns the growing chain North Italia, acquired in 2019, as well as Fox Restaurant Concepts, whose upscale, fast casual restaurants the chain sees as a vehicle for expansion.)

A key growth point, the report notes, has been an increase in takeout and delivery orders, which accounted for about 25% of total sales in 2022.

Last year was bruising for a restaurant industry still recovering from pandemic shutdowns and buffeted by rising costs and labor shortages. But during the first nine months of 2023, the Calabasas Hills company racked up increased sales and income, and continued to expand.

The chain has differentiated itself with ample portions, a variety of “craveable” dishes difficult to replicate at home and the fact that it, unlike some competitors, still prepares everything from scratch at each restaurant, said Joshua Long, who follows the company in his role as managing director of the financial services firm Stephens.

“The brand,” Long said, “has really found a spot in the hearts of consumers.”

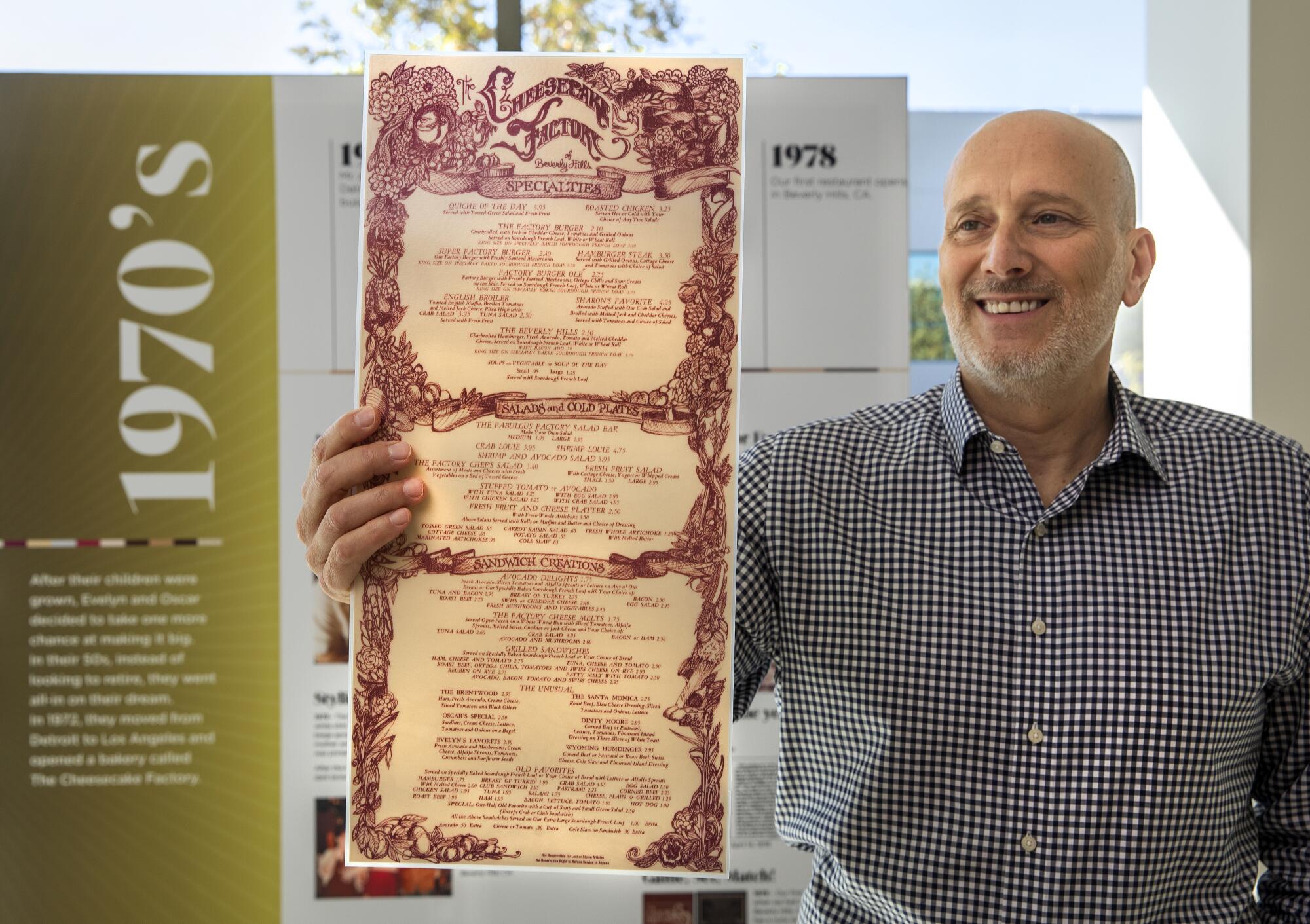

As the company grew, so did the length of the menu.

It started as a single page, front and back, of items simple enough that, if a chef walked out on him, Overton could make them himself — a factory burger, which sold in the early days for $2.10, the Avocado Delights sandwich for $1.75, a slice of cheesecake for $1.25.

For several years, Overton’s taste buds kept him from adding fish to the menu, and he also dragged his feet on selling steak, because of its price tag.

“If you went on a date,” he said, “I didn’t want anybody ordering the steak and you couldn’t afford it.”

Whenever he ate at a rival restaurant, he kept an eye out for dishes he could simplify or transform. During a meal at the Peninsula Beverly Hills years ago, he saw a menu item of cheese straws with avocado, which inspired the idea for avocado egg rolls, now a top seller.

“How did I let the menu get so big?” Overton said. “I didn’t know what the heck I was doing. If I knew what I was doing and understood the restaurant business, it probably wouldn’t have turned out this way.”

But it worked — and today, it’s become a key marketing tactic.

The sheer size of the multi-page, spiral-bound menu has earned a ribbing from Ellen DeGeneres and inspired Halloween costumes and a BuzzFeed list of jokes, including one that, given the menu’s girth and cultural relevance, compared it to the Bible.

“We get so much PR just cause of that big menu,” Overton said, smiling. “I always say that our greatest difficulty is the size of the menu, but our greatest defense against competition is the size of our menu.”

The menu items themselves are a cacophony of calories.

Every year, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a nonprofit health advocacy group, releases an “Xtreme Eating Awards” list of single restaurant dishes that contain about a full day’s worth of calories. Two Cheesecake Factory items made the latest list — an Italian combo plate at 2,800 calories and a French Dip cheeseburger with fries at 2,200.

But when you bring up calories with Overton, he looks unfazed — decadence is part of the brand, and besides, he says, people rarely finish a dish in a single sitting.

“We’re the king of doggy bags,” he says. “I don’t pay a lot of attention to calories, because we let people choose what they want.”

But if there’s one thing Americans want more than delicious, fattening food, it’s the idea — the vow — that they will soon eat less of it. Enter: SkinnyLicious, the brand’s name for menu items with fewer than 600 calories, which was added to the menu in 2011.

SkinnyLicious items, Overton said, account for around 15% of sales.

In the winter of 1993, David Gordon, now the company’s president, was looking for a job as a restaurant manager.

He had applied to two places, including a Cheesecake Factory on the Westside, but was more interested in the other small chain — until he had his Cheesecake Factory interview.

The people interviewing him ate a burger in the middle of the interview — “a little strange,” Gordon says — and steered the conversation toward the intricacies and caliber of French fries. Over 20 minutes, they discussed everything from starch levels to how hollow the fries felt when you bit into them.

“It intrigued me,” Gordon said. “This is somewhere where quality is incredibly important.”

Early in his career at the company, Gordon recalled asking the person in charge of operations if there was a chance he would be transferred. He was planning to buy a house in Redondo Beach, Gordon explained, but didn’t want to if he might be moved.

“No, no, fantastic, things are great,” he recalled being told.

But a few months later, the man in charge of operations asked him to move to Woodland Hills, promising Gordon that, within a year, he would get him back to the location closest to his home. As the year mark approached, the boss kept his commitment.

“He cared about me as a person,” Gordon said, noting that the company still works hard to live out that ethos.

Founded in West Hollywood 25 years ago, Barry’s helped launch the era of the modern boutique fitness studio. Its glamorous devotees wouldn’t sweat anywhere else.

Cheesecake Factory locations are notoriously busy, so if you’re going to ask workers to be slammed all day and prepare and serve more than 200 different items from scratch, the workers need to feel a connection to the restaurant and the people they work for, Gordon said.

Last year, the Cheesecake Factory, whose restaurants employ about 35,000 people, was one of only two restaurant chains — Panda Express’ parent company was the second — to earn a spot on both Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For and People’s Companies that Care lists, which survey employees about company culture, pay, retention, opportunities and fairness.

Their reputation for conscientiousness took a hit in 2018 when the California Department of Industrial Relations held the company and two janitorial contractors jointly liable for more than $4 million in wage theft violations after an investigation found the contractors’ employees assigned to eight Southern California Cheesecake Factory restaurants didn’t get proper rest or meal breaks and weren’t paid overtime while waiting for kitchen managers to review their work at the end of a shift. Although Cheesecake Factory didn’t directly employ the workers, state law dictates that companies relying on subcontractors for labor can be held liable for workplace violations.

In January, the California Labor Commissioner’s Office announced that it had reached a $1-million settlement against the company and both contractors.

Sidney M. Greathouse, the vice president of legal services for the Cheesecake Factory, issued a statement that said “the company denies any wrongdoing and no longer utilizes the services of the janitorial companies at issue in the case.”

Today, the company sells more than 30 varieties of cheesecake, but a massive painting of one of the originals — a simple slice topped with strawberry filling — hangs above Overton’s desk in his office that looks out on the hills of Calabasas.

Sprawled across his desk are several stacks of folders each about a foot high. He’s a few years from 80, but between work and spending time with his wife, children and grandchildren, he doesn’t have much down time.

“I have no time for hobbies,” he says. “I don’t play golf. I don’t do any of that.”

He thought back on his 20s, around the time he started the business, when he first learned that you didn’t have to print your signature literally, but could sign it however you wanted.

He played around with it and, as he wrote, let emotion guide him, creating a flowing capital D, which then exploded into 14 looping, semi ovals that start big and trail off.

“It’s an emotion,” he said. “I just felt like I was moving forward.”

Through the years, a few people had mocked his signature, he said, including someone who wrote to him saying, “I’m so sorry, with a signature like that, I won’t be investing in your company.”

But he stuck with it. His gut hasn’t failed him yet.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.