Lynn Conway was the bravest person I ever knew.

It wasn’t merely her struggle to make her way in the male-dominated computer engineering world of the 1960s and 1970s. It was that she did so, with spectacular success, while contending with her own psyche, her family and her bosses at IBM to complete her transgender transition.

Conway died Sunday, according to her husband, Charles Rogers, at home in Jackson, Mich., of a heart condition.

As I recounted in 2020, I first met Conway when I was working on my 1999 book about Xerox PARC, “Dealers of Lightning,” for which she was a uniquely valuable source. In 2000, when she decided to come out as transgender, she allowed me to chronicle her life in a cover story for the Los Angeles Times Magazine titled “Through the Gender Labyrinth.”

Thanks to your courage, your example, and all the people who followed in your footsteps, as a society we are now in a better place.

— IBM apologizes for firing Lynn Conway for her gender transition in 1968

That article traced her journey from childhood as a male in New York’s strait-laced Westchester County to her decision to transition. Years of emotional and psychological turmoil followed, even as he excelled in academic studies.

He won admission to MIT, but flunked out due to a lack of social or medical support. What would have been Conway’s MIT graduation day found Conway in San Francisco, living on the fringes of the gay community, searching for how to fit in as a male. But he did not see himself as a gay man attracted to other men, but as a woman attracted to other men.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In 1961 he enrolled at Columbia University, acquiring bachelor’s and master’s degrees in electrical engineering in only two years. That led to a position on a team at IBM secretly designing the world’s fastest supercomputer, a pet project of IBM President Thomas Watson Jr. Conway moved with the team to Menlo Park, Calif., in the years before the surrounding landscape was dubbed Silicon Valley.

By then Conway had gotten married and was raising two daughters. But family life intensified his inner turmoil, and in 1968 he decided to undertake gender reassignment surgery.

As I wrote in 2000, Conway had visualized a nearly seamless transition. IBM was supportive, at least at first. It was willing to change the name on company records and execute a transfer to another lab, giving the employee henceforth known as Lynn Conway a fresh start.

But even as the $4,000 operation was still in the planning stage, it became clear that IBM executives could not understand how a transgender employee could fit into a corporate culture that was “still white shirt, blue serge suits and wingtip shoes,” as Conway’s IBM supervisor told me. “This simply wasn’t the IBM image.” The company fired him.

Decades later, Conway was philosophical and nonjudgmental about IBM’s decision. Gender transition and sex reassignment surgery were alien concepts at the time.

“Christine Jorgensen was the last time anything had come out about stuff like this,” Conway told me in 2020. Jorgensen’s transition, which had made front-page news in 1951, had been reduced to a historical curiosity nearly two decades later. T.J. Watson Jr., the president of IBM, “was thinking there would be endless publicity, and I can understand that.”

Lynn Conway’s brilliant contributions to computer science didn’t stop IBM from firing her during her gender transition. Now it has apologized.

The family went on welfare for three months. Conway’s wife barred her from contact with her daughters. She would not see them again for 14 years.

Beyond the financial implications, the stigma of banishment from one of the world’s most respected corporations felt like an excommunication.

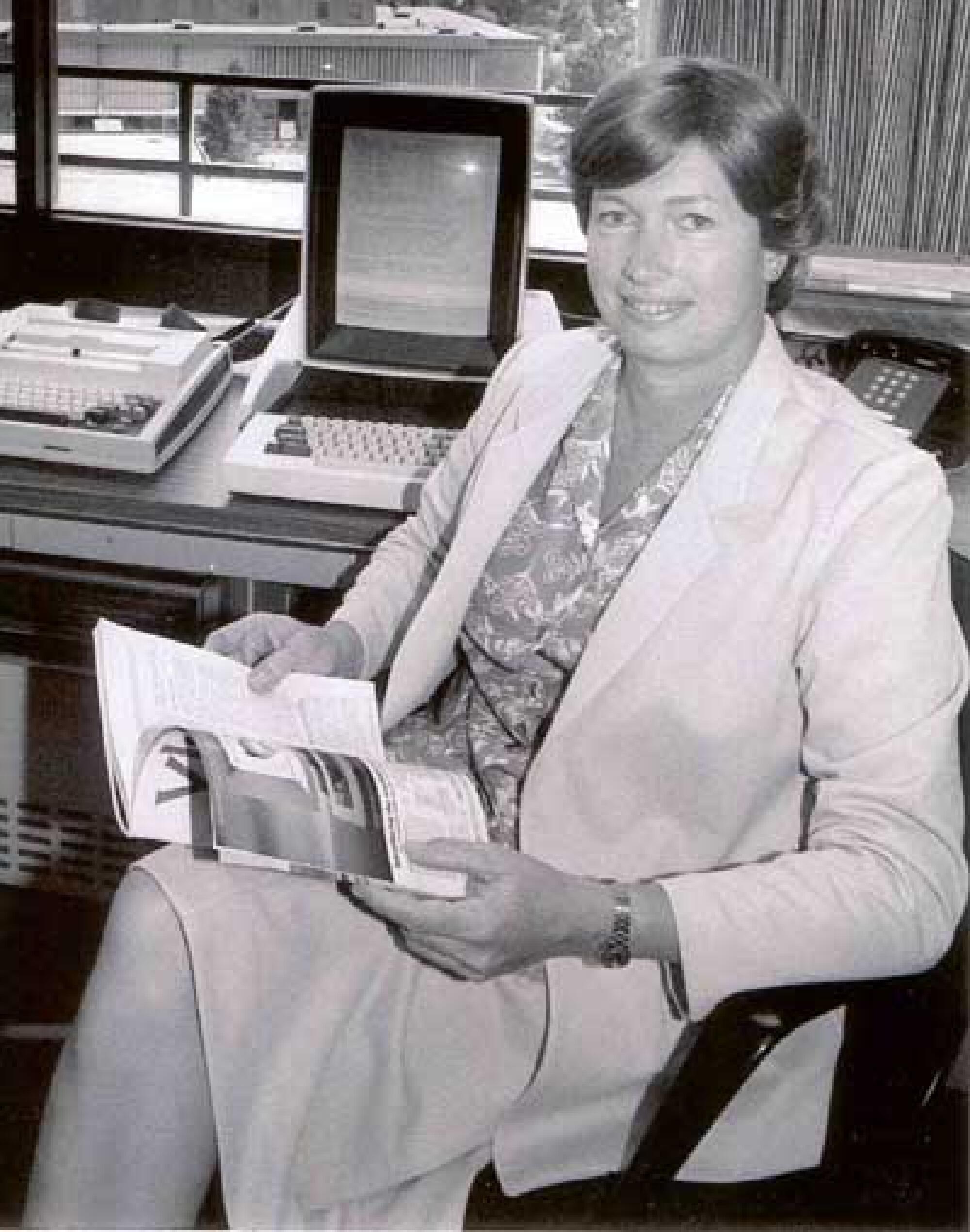

She sought jobs in the burgeoning electrical engineering community around Stanford, working her way up through start-ups, and in 1973 she was invited to join Xerox’s brand new Palo Alto Research Center, or PARC.

In partnership with Caltech engineering professor Carver Mead, Conway established the design rules for the new technology of “very large-scale integrated circuits” (or, in computer shorthand, VLSI). The pair laid down the rules in a 1979 textbook that a generation of computer and engineering students knew as “Mead-Conway.”

VLSI fostered a revolution in computer microprocessor design that included the Pentium chip, which would power millions of PCs. Conway spread the VLSI gospel by creating a system in which students taking courses at MIT and other technical institutions could get their sample designs rendered in silicon.

Conway’s life journey gave her a unique perspective on the internal dynamics of Xerox’s unique lab, which would invent the personal computer, the laser printer, Ethernet, and other innovations that have become fully integrated into our daily lives. She could see it from the vantage point of an insider, thanks to her experience working on IBM’s supercomputer, and an outsider, thanks to her personal history.

After PARC, she was recruited to head a supercomputer program at the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA — sailing through her FBI background check so easily that she became convinced that the Pentagon must have already encountered transgender people in its workforce. A figure of undisputed authority in some of the most abstruse corners of computing, Conway was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1989.

She joined the University of Michigan as a professor and associate dean in the College of Engineering. In 2002 she married a fellow engineer, Charles Rogers, and with him lived active life — with a shared passion for white-water canoeing, motocross racing and other adventures — on a 24-acre homestead not far from Ann Arbor, Mich.

In 2020, she received an unexpected gift: A formal apology from IBM for firing her 52 years earlier. At an emotional ceremony witnessed by 1,200 IBM employees signed on to a company website, Diane Gherson, an IBM senior vice president, told her, “Thanks to your courage, your example, and all the people who followed in your footsteps, as a society we are now in a better place.... But that doesn’t help you, Lynn, probably our very first employee to come out. And for that, we deeply regret what you went through — and know I speak for all of us.”

At Michigan, she is remembered for her “positive outlook, warm encouragement, creativity and ‘singular vision,’” the university observed in a retrospective posted Tuesday. “Conway described herself in 2014 as a perennial beginner, never afraid to take on learning how to do new things.”

Her role as a leader in the transgender community may be even more important than her role in the extraordinary advances of the technology revolution of the late 20th century. She fought not a few battles over anti-transgender discrimination and what she called “the systemic psychological pathologization of gender variance.”

On her personal website she reflected with well-deserved pride of having used the website to offer “gender transitioners ... information, encouragement and hope for a better future.” When she began to do so in 2000, she recalled, “trans women especially were considered sexually-deviant and mentally-ill by prejudiced psychiatrists and psychologists. By compiling stories of those who went on to fulfilling lives after transition,” she wrote, she tried to provide “role models and hope for the many people then in transition.”

She added , “Fortunately, those dark days have receded. Nowadays many tens of thousands of transitioners have not only moved on into happy and fulfilling lives, but are also open and proud about their life accomplishments.”

It’s a reproach to our society and our politics that Lynn’s confidence that the “dark days” of transgender discrimination and prejudice were past has proven to be premature. I hope that she didn’t allow herself to be too discouraged by the cynicism and hypocrisy of the political leadership in some of our most benighted states, and that she never forgot the extraordinarily positive impact she had on all the communities, professional and personal, of which she was a member.

Lynn Conway faced more challenges in her life than most of us can contemplate. She should be remembered as someone who, to paraphrase William Faulkner, not only faced them, but prevailed over them. And in doing so she enriched us all.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.