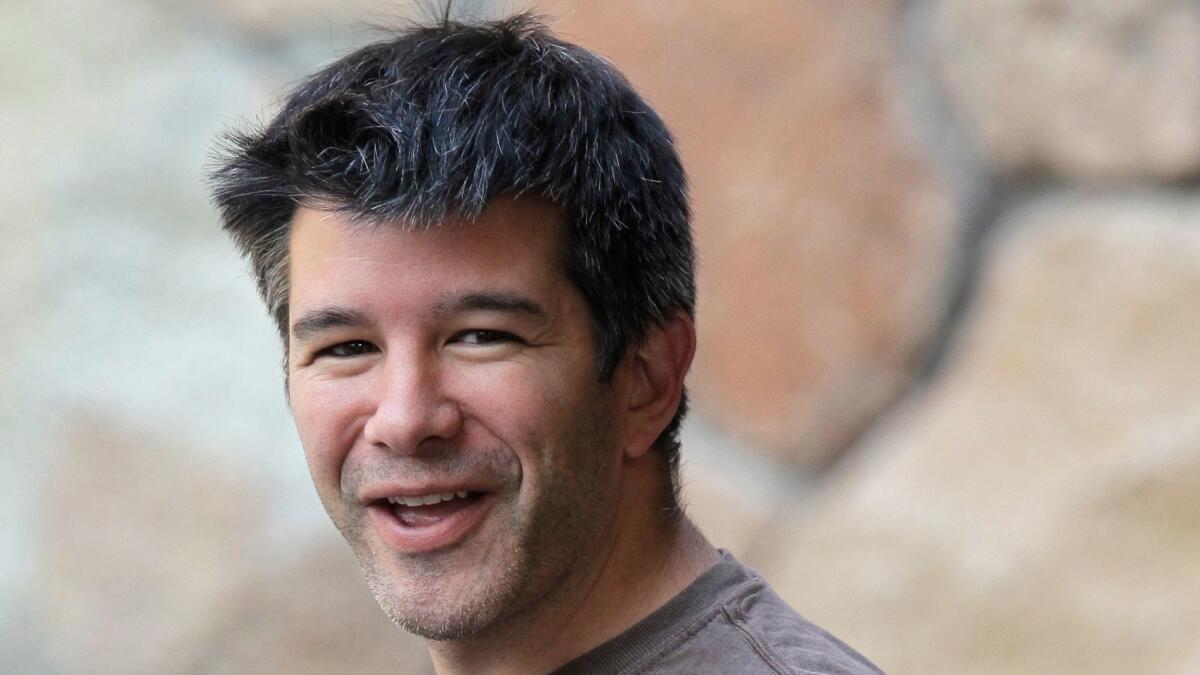

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick is on leave. Now what?

- Share via

When chief executives take a leave of absence, it’s typically because they have a serious problem on their hands. So when Uber co-founder and CEO

Kalanick’s announcement came at a tumultuous time for Uber. Former U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. had just wrapped up a months-long investigation into allegations of systemic sexual harassment, discrimination and bullying at the company. Holder’s firm, Covington & Burling, had made 47 recommendations on how Uber could address its toxic culture.

Kalanick’s move signaled a shift in the company’s too big-, too hot- and too-innovative-to-fail attitude. It was an admission that as CEO he had to bear some of the responsibility for the mess in which Uber now found itself.

But his leave of absence means a lot more, business and management experts said.

What does it mean for a CEO to go on leave?

When CEOs go on leave, it means that they’re taking a break from their day-to-day duties and that others will step in to perform their roles. It’s different from taking a vacation because it signals that the executive, for whatever reason, is unable to effectively do his or her job at that point in time.

One of the more common reasons for executives taking a leave of absence is health issues, said David Mayer, a professor at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

Steve Jobs, for example, took multiple leaves of absence from Apple when he was receiving cancer treatment. Patrick Byrne, chief executive of Overstock.com, went on indefinite leave last year because of hepatitis C complications. He returned three months later.

“Another reason a CEO might go on leave is because there are performance or ethical issues,” Mayer said.

David Baazov, who was chief executive of online gambling company Amaya, took an indefinite leave of absence in March 2016 after he was accused of insider trading. He resigned from the company five months later.

Kalanick has not given a timeline for when he expects to be back.

Why would a board of directors put an executive on leave instead of just firing him or her?

Putting an executive on leave doesn’t necessarily mean that a board of directors has lost faith in that person, said Micah Alpern, an organizational and leadership expert at A.T. Kearney.

“It could be that there are things going on in their personal life, that they’re distracted and are not able to manage right now,” Alpern said. “It doesn’t signify that they don’t think they’re the right person to run the company in the long term.”

In Kalanick’s case, he cited his mother’s recent death in a boating accident as the reason for wanting to take time off.

One possible reason for putting Kalanick on ice instead of firing him is that Kalanick and his allies on the board — Garrett Camp, Uber’s co-founder, and Ryan Graves, senior vice president of operations — reportedly have disproportionate voting rights that would make it difficult for other board members to oust him.

But even if the board could fire Kalanick, Silicon Valley has shown a reluctance to get rid of founders who are perceived to be the secret sauce in a company’s success.

“Travis explained his vision to me of a future where no one owned a car, there was no need for parking lots, less congestion, fewer accidents, fewer DUIs,” said Bradley Tusk, founder of Tusk Strategies, who has worked with Kalanick and Uber in the past, but is not a member of the company’s board. “That was back in 2011. It's just as cogent and accurate of a vision today as it was then. Not having him driving the vision would be a mistake.”

What are the benefits to putting the CEO on leave?

First, it’s good symbolism, according to Alpern, who said it sends a strong message to employees and the public that the company is serious about changing.

But it’s also an opportunity for the executive to reflect, to undergo leadership training and for the company to implement changes without the distraction of a beleaguered CEO.

“The CEO is typically the leader that the culture of an organization is anchored around,” said Gary Mangiofico of the Pepperdine Graziadio School of Business and Management. “So if they want to see a culture shift in the organization, they have to dislodge that anchor, if you will, in order for people to even believe there’s a possibility things will change.”

Are there any downsides?

In Uber’s case, not having a second in command step up to fill Kalanick’s shoes while he is away could create uncertainty at the company, Mangiofico said.

The firm is currently without a chief operating officer, a chief marketing officer, a chief financial officer, a head of engineering or general counsel. Kalanick’s duties will, instead, be spread among the 14 people who report directly to him.

“Without a central leadership figure, the vision of a company can start to become fuzzy,” Mangiofico said. “And if that happens, the strategy potentially begins to break down.”

The indefinite nature of Kalanick’s leave of absence could also hurt morale, Alpern said.

“An employee is sitting there thinking, I can focus on my job, but they’re also going to think about what’s going to happen to our role or our policies? What will it be like to work here?”

So what happens when Kalanick comes back?

In Holder’s report, the top recommendation was for the company to review and reallocate some of Kalanick’s responsibilities. This could mean that he returns as a CEO who gets support from a newly hired COO. It could mean that he is moved into another role entirely.

Based on Kalanick’s talk about taking time off to reflect and work on himself, the expectation of investors and other stakeholders is likely to be that if he returns, he will do so as a changed man.

“There’s going to be a lot of skepticism around it,” Mayer said. “Employees and stakeholders will have their antennas up.”

The company and its board will have to figure out a way to measure that change and to hold Kalanick accountable. Otherwise the Holder report and Kalanick’s leave of absence will just be lip service, business and management experts said.

“Culture matters a lot, and over time it has a significant impact not just on the people but on the bottom line,” said Jim Barnett, co-founder of human resources platform Glint. “Companies that fail to create inclusive environments where people feel a sense of belonging will struggle to succeed in the new work world.”

tracey.lien@latimes.comTwitter: @traceylien