For high school seniors, return to campus is a trip back in time

- Share via

This is the April 26, 2021, edition of the 8 to 3 newsletter about school, kids and parenting. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox every Monday.

It’s another week of transitions for California students.

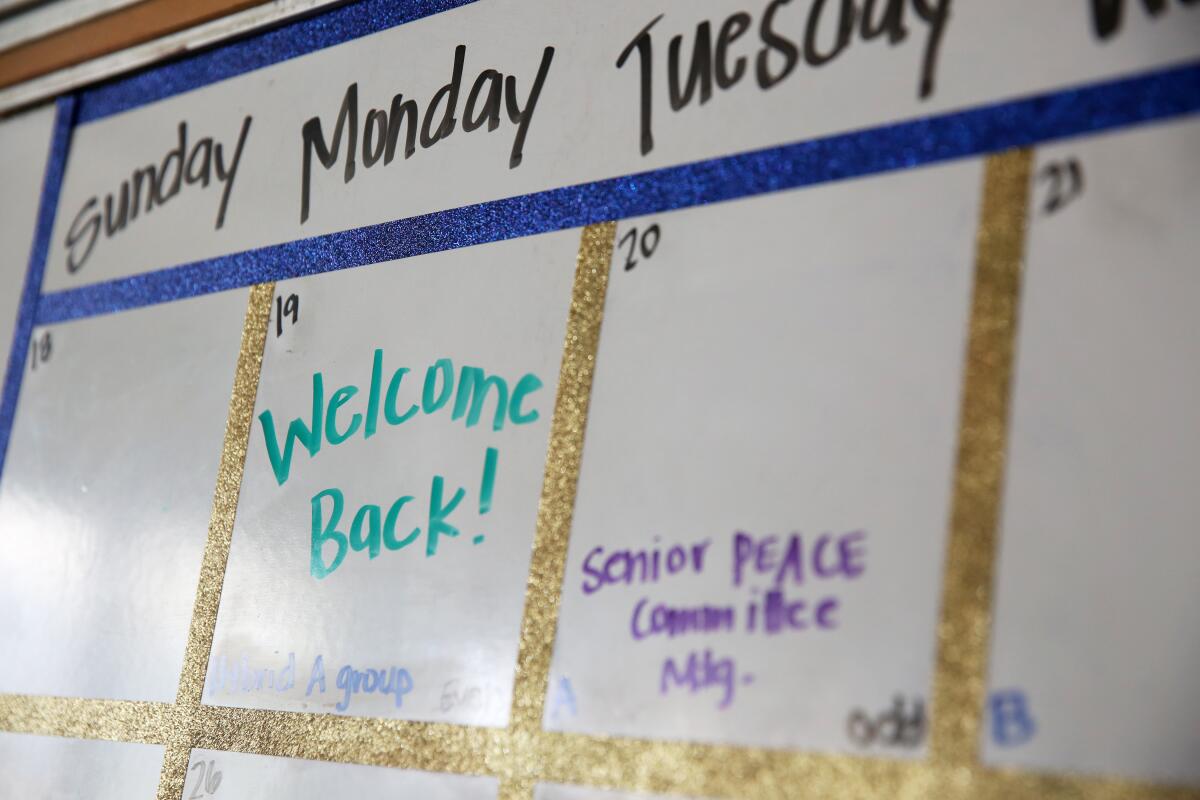

Last week, I wrote about kindergartners, who entered the classroom for the first time this month in a quantum leap forward. Now, I want to turn to the opposite end of the K-12 spectrum — high school seniors. If kindergartners were hurtling into the future, these soon-to-be graduates may feel more like they’ve entered the Twilight Zone.

Some of this is logistics: Fewer than half of California high school students currently have the option to learn in person, and among those who do, just a sliver have decided to return. At most schools, only half of those will be on campus on any given day, and many will still be learning on laptops from their classrooms.

“Routines will be really helpful,” advised Daisy Camacho-Thompson, assistant professor of psychology at California State University, Los Angeles. “They don’t have to be marked or purposeful mental health routines; it can be every day we go for a walk after school, or every night we prep the food for tomorrow — just to have something that you can expect that will be the same every day.”

Still, experts say many of those reentering high school this spring aren’t so much returning to campus as reverting to a previous form. That’s especially true for seniors who’ve spent the past year helping support their families, whether by caring for younger siblings who are stuck at home, or by going out to work full time.

Officials have struggled to identify just how many students have taken on these grown-up roles amid the pandemic, which crushed many California families under the dual weight of infection and economic hardship. But anecdotes abound.

“We had many cases where a single mom got laid off from work, so the student steps in saying, ‘I gotta do something or we’ll lose our apartment,’” said Ricardo Mireles, principal of Academia Avance Charter School in Highland Park. “There’s even anecdotes of students who got sick at work, went home, and got their family sick.”

Neither Mireles nor any other administrator knows exactly how many California high schoolers have entered the workforce this past year. Many students never told their teachers they were working. Others didn’t tell their bosses they were still in school.

That’s how Fran, a senior at Avance, ended up working 50 hours a week as a cashier at a local restaurant.

“At first I didn’t say anything about my school,” said the Berkeley-bound 18-year-old, who asked me to identify her by her nickname because of her immigration status. “[Eventually] my manager helped me fix my schedule, once she understood I’m still a student. Now I’m working just 35 hours.”

The decision had been an intuitive one: Her mother lost work, their rent became unmanageable, and even after they’d moved, the bills were overwhelming. Still, keeping up with classwork while pulling shifts five days a week left her worn out. When we talked, she was about to go back to learning in person — another challenge in a year that’s been full of them.

”It’s going to be hard,” she confessed. “I get out of work at like 10:45 p.m., so I’m kind of tired.”

Balancing work with school isn’t new, but the pandemic made it more urgent, and probably more widespread, than in normal years. Remote learning also created the need for some adolescents to become caregivers at the same time it made it easier than ever for others to work.

As my colleague Laura Newberry reported in February, many have seen their grades slip and their mental health suffer as a result. Seventeen-year-old Luis Leon told Laura his brain was fried by working, caring for his younger siblings, and trying to keep up with school.

Still, others have thrived.

“It can be normal and rewarding for teenagers to help out their families,” said Camacho-Thompson, the psychology professor. “They’re assisting their families in culturally normative ways, which they find rewarding and builds their sense of identity.”

Indeed, Fran said she was proud of everything she’s done this past year. Still, she was eager to get back to school.

“I just want to start getting used to being in a classroom, being able to pay attention, because that’s been really hard on Zoom,” the senior said. “I want to be ready so college will not be a drastic change for me.”

Fran plans to double-major in economics and poli sci at Cal and hopes to become an immigration lawyer. Ultimately, those dreams are what pushed her to cut her hours at work and head back to her desk at Avance.

“[My mom] said it’s going to be hard, but she understands,” she said. “I’m not doing this just because it’s fun — I’m going to college because I want a better education and to be financially stable.”

The vaccine, too, has helped ease the transition.

“Now I’m more relaxed about it,” she said of her return to school. “I’m feeling like it’s normal again and that we’re just high school seniors.”

More than 60,000 California kindergartners were no-shows this year

Here’s what it means for elementary schools in fall 2021: Amid school closures during the pandemic, kindergarten enrollment plunged in California and nationwide and educators are bracing for an influx of new students come fall. In Los Angeles Unified alone, kindergarten enrollment dropped by 6,000 students, or 14% — with the biggest drops generally coming from neighborhoods with the lowest household incomes, according to Supt. Austin Beutner.

Some of the missing students attended private school, others were home-schooled, and still others may not have received formal schooling at all.

California, like many states, does not mandate kindergarten, so the no-show children could begin either kindergarten or first grade this fall. The decision will be up to parents in concert with their schools and districts, with some guidance likely to come from the state as it works to support parents on myriad issues as they transition back to in-person learning this fall, a California Department of Education spokesman said.

The nonprofit education research group NWEA published a brief explaining what teachers, schools and districts should keep in mind as they prepare to bring these students into the classroom. Districts may have larger and more split-age classes for kindergarteners and first-graders, the research brief said. Because kindergarten is normally a time in which students learn “how to do school,” such as sitting on the floor with legs crossed, raising a hand to speak, or forming a line to go outside, many more students than usual are likely to be unfamiliar with in-person classroom routines.

Research has shown that children already enter kindergarten with disparities in their academic and non-academic skills, stemming in part from disparities in access to early learning opportunities.

Preschool enrollments are also down this year, the brief said, meaning more students will enter school next year without having been in a formal school environment. Districts are looking at how to use summer school and enrichment programs to help them transition.

Research is mixed on whether holding kids back a year has positive or negative effects. One recent study found that older students had higher initial math and reading scores and higher initial growth when they began kindergarten but grew less than younger students did during the first and second grades.

Enjoying this newsletter?

Consider forwarding it to a friend, and support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

Did you get this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every week.

Do later school start times improve grades?

Not so much, according to one study in Minnesota. Researchers looked at 18,000 students in grades 5 through 11 after four school districts pushed back the start of the school day by 20 to 65 minutes, according to The Hechinger Report, a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on education. Student grades increased a little, an extra 0.1 points, on average. The better news could be that after the switch in start times, students were 16% more likely to meet the recommended hours of sleep, which is nine or more hours for students in grades 5 and 8 and at least eight hours for students in grades 9 and 11.

Sleepy-head kids in California have one more year to wait for later start times under a law approved in 2019. Beginning in the 2022-23 school year the law will be phased in, ultimately requiring public middle schools to begin classes at 8 a.m. or later while high schools will start no earlier than 8:30 a.m.

A superintendent’s swan song, and other news

The big education news of the week in L.A. was the announcement by Los Angeles Unified School District Supt. Austin Beutner that he’d be stepping down when his contract expires on June 30. Beutner (a former Times publisher) was not your typical superintendent. A career businessman, he had little hands-on experience in education. Although he clashed with the teachers union and sometimes with the school board, he won some admirers, especially as he navigated the district through the COVID-19 pandemic this past year. The school board appointed Megan Reilly, who oversees the district’s massive finance, business and operations arm, as interim superintendent.

Here are some of the other education-related stories we’ve been following:

It was a good week for a Santa Ana High School student, one of three members of her graduating class to be accepted to Harvard. What set Stephany Gutierrez apart are some of the other schools she got into: Columbia, Dartmouth and Brown, all in the Ivy League. KNBC-Channel 4 has the story — and the video.

Fresno Unified released plans last week for graduation ceremonies next month — for two years’ worth of graduates. Not only 2021, but also 2020, grads will be offered the opportunity to walk across the stage. Here’s the story from the Fresno Bee’s Education Lab.

There’s remote learning, and there’s remote learning. The New York Times reports on schools around the country, including California, that are seeing students Zooming in from rather far-flung locations. One teacher in Brooklyn said he had students logging in from Yemen, Egypt and the Dominican Republic. But that’s nothing compared with Elizabeth, N.J., where on one recent day, records show that 767 students were attending class from 24 countries.

Andrea Lopez-Villafaña at the San Diego Union-Tribune profiles Chula Vista middle school principal Luis Aparicio and his evolution from rebellious high school dropout to teacher and school administrator. “I ... convinced myself that [with] hard work and determination — and having someone to guide you even through dysfunctionalities — you could get places. Education kind of became the equalizer for me,” he said.

Finally, the San Francisco Chronicle‘s Susie Neilson reports on a demographic phenomenon that will be shaping California schools beginning in about five years: The state’s birth rate plunged by 15% during this past pandemic year, with even larger declines in some counties, including San Francisco and Los Angeles. “It’s going to take a while to figure this out, but there’s no way of getting around that this is a very large-scale event,” Philip Cohen, a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, told the Chronicle.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.