How much did L.A. test scores improve over the last year? Beutner touts ‘real progress’

- Share via

Los Angeles schools Supt. Austin Beutner touted gains in student achievement, rising graduation rates and lower absenteeism as “real progress” and evidence that the nation’s second-largest school district is making strides in his annual State of the Schools speech Thursday.

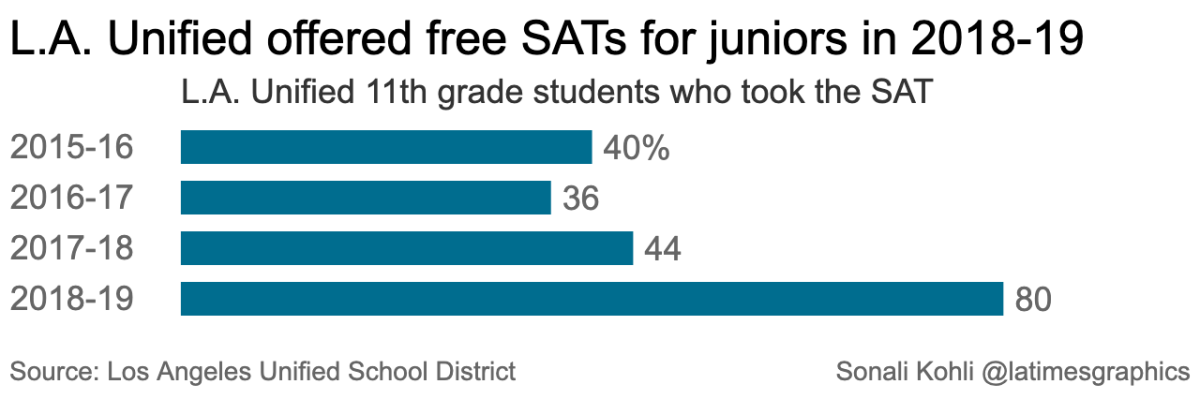

A gain of 1.6 percentage points over the previous school year on state tests in English and 1.9 percentage points in math represent an upward pace that some experts regard as realistic and even commendable if they can be sustained over the long term. Graduation rates increased just under 1 percentage point and absenteeism is down by half a percentage point. In the biggest jump, 80% of high school juniors took the SAT college admissions test, up from 44% a year ago, thanks to the district providing free testing during the school day.

“By traditional standards, we’d say it was an extraordinary year,” Beutner said in an interview before the speech. “Everything that we wanted to see go up, went up. Everything we wanted to see be reduced was reduced.”

Some education activists and groups, however, consider such incremental climbs far too small and do not address the large achievement gaps separating white and Asian students from Latino and black students.

“At this rate of improvement, the children now in kindergarten will be 65 years old before every kid in Los Angeles can read,” said Seth Litt, executive director of the local advocacy group Parent Revolution, which recruits parents on behalf of causes it supports. “Are we OK to live in a city where poor children, where black children, where Latinx children do not have a chance of success?

“It looks like the superintendent has become a true believer in incrementalism,” Litt said.

In his address, Beutner insisted the data show that “because of the dedication and hard work of those in this room and our 60,000 colleagues, we’re truly making real progress.” He spoke before an audience of nearly 2,000 that was mostly administrators, but also included invited guests and dignitaries.

The district’s biggest problem he said, is insufficient funding, a theme he has returned to repeatedly. And this shortfall, Beutner said, directly affected all areas in which the district needs to be much better.

He noted that 56% of students still fall below proficiency in English; 67% in math. Only about 10% of students from low-income families are proficient in both English and math. And of 100 students who enter ninth grade, only 12 will graduate from college.

Other areas also showed incremental progress.

Suspension rates continued to go down, but the big drop was in previous years. The same holds true for the preliminary graduation rate increase from 77.3% to 78.1%, with the biggest leaps in earlier years. And underlying questions remain about both statistics. Many teachers and some principals complain about discipline issues arising from the drop in suspensions. Also, the district has never deeply examined questions that arose about the rigor of credit recovery courses that propelled graduation rates.

Chronic absenteeism is down, but this was essentially the drop from an upward spike of the previous year: In the first semester of 2016, 12.7% of students were absent about 16 days or more. The following year the number rose to 13.2%. Last year, it was back to the same 16 level of 12.7%.

Some philanthropists and civic leaders hailed the May 2018 hiring of Beutner, a businessman with no experience running a school or school district. He was widely regarded as a member of their tribe in school reform, someone willing to make tough and monumental decisions against status quo interest groups.

That hasn’t happened yet, said Fred Ali, president and chief executive of the Weingart Foundation, which contributed to a $3-million fund that Beutner used to tap outside expertise.

“I know there has been a lot of work that has been done and I’m hopeful that some of that work will result in some change,” Ali said.

Beutner’s relatively short tenure has included the rare challenge of managing a six-day teachers’ strike, for which he received mixed reviews.

On Thursday, Beutner warned against magic-bullet solutions.

“L.A. Unified is a complex organization,” he told administrators. For students, families, teachers and principals, “disruption is not what they need. They need stability and continuity. ... Dramatic plans have not worked elsewhere and they will not work in L.A. Unified.”

He added: “Our schools should not be test kitchens with the recipe changing every 24 months.”

In that tone, Beutner sounded a lot like recent Supt. Ramon C. Cortines, who retired in 2015. Cortines was widely regarded as a capable administrator, but was criticized by some reform advocates as “not moving fast enough.”

Beutner said the mission ahead was like the war on poverty or the goal of putting a man on the moon — people needed to be in it for the long haul.

“It is time for our moonshot in public education,” Beutner said. “There will be doubters just as there were in the 1960s.”

Josemie Jackson, the administrator of two early-education centers in San Pedro, was struck by the moonshot reference. If man can reach the moon, she said, “then we can make it: helping students be self-sufficient, to go to college, to their career, to be citizens in this society.”

She and other administrators also support Beutner’s emphasis on cutting down on bureaucratic mandates and paper-pushing that take away from their time with students and teachers.

Beutner did not lay out a specific plan or goal as his moonshot, but he’s embraced a decentralization plan that is supposed to bring decisions and resources closer to schools and make it easier for parents to be involved.

Such local control is strongly supported by school board President Richard Vladovic, whose vote was key in hiring Beutner and whose support remains crucial to Beutner keeping his job.

Beutner’s emphasis on vastly improved funding aligns closely with the thinking of board member Jackie Goldberg. She won a special election to fill a vacant board seat and is expected to exert an outsized influence on the board.

After the address, board member Scott Schmerelson praised the recognition of funding needs, but “what I did not hear was a plan for generating the additional resources and support that our children need and deserve.”

It didn’t come up Thursday, but Beutner is skeptical about another district plan currently in its final stages of development: a system to rate schools on a scale of 1 to 5. That effort is strongly supported by board member Nick Melvoin. Melvoin was part of a narrow board majority elected with substantial financial backing from advocates for charter schools.

Melvoin’s priorities extend well beyond supporting charter schools, but he is generally associated with those pushing for more rapid change. Melvoin was among those who had pressed for hiring Beutner, but his influence has waned somewhat with Goldberg’s election in May.

In contrast, Goldberg’s arrival means that unions representing teachers and administrators are likely to have a louder voice. Goldberg was greeted enthusiastically when board members were introduced Thursday.

Board member Monica Garcia said she felt Beutner hit the mark.

“His desire to remove obstacles and support the leaders of our schools was evident and focused,” Garcia said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.