Column: He died homeless and alone, but his wife had never lost hope he’d return.

- Share via

L.A. County coroner’s investigator Adrian Munoz had one last duty to perform in the case of Alvin Robinson, a homeless man whose body was retrieved from a West L.A. sidewalk: making the call no one wants to receive.

He dialed a Las Vegas phone number and a woman picked up.

“I asked if she knew anyone by the name of Alvin Robinson and she said yes, that was her husband,” said Munoz. “I told her that unfortunately he was discovered deceased by the Los Angeles Police Department.”

Lola Robinson had to compose herself. For years, she wondered where her husband was, and she never let go of the hope that he’d come back home. But she had also worried that a call like this might come.

Alvin Robinson, 61, was found sprawled face down Sunday on Massachusetts Avenue near Sepulveda Boulevard. I arrived at the scene at the same time as investigator Munoz. It was unclear how Robinson had died, but he had a surgical scar on his chest and prescription medication in his backpack. Blood had puddled on a cardboard mat near his mouth.

In L.A. County this year, nearly three homeless people are dying each day on the streets, in vehicles, shelters, hospitals and parks. Robinson was the third homeless person to die Sunday, and the 680th this year. By Friday afternoon, 18 more had died, bringing the count to 698.

There’s a lot I could say about that, but the numbers don’t need my amplification. You only have to do the math. There are an estimated 60,000 homeless people in the county. If the current pace continues, more than 1,000 of them will die, topping last year’s total of 921. That’s one in 60.

We’ll never know all their back stories, but having watched Munoz load Robinson’s body into a coroner’s van, I wanted to know this one. Maybe there’d be something in it to help us figure out what everyone wants to know:

How did we end up with as many homeless people as Arcadia has residents, who are they, and what do we have to do to get in front of this epidemic?

Lola Robinson arrived at the Greyhound bus station in Los Angeles before dawn Thursday. She had taken an overnight bus from Las Vegas, traveling with her son, Stephan, to claim her husband’s property and make burial arrangements.

When I picked them up, I already knew part of Alvin Robinson’s story because I’d spoken to Lola and Stephan by phone. Lola met Alvin at a party in Bakersfield when they were in their 20s. They married in 1984, had five children and every expectation of a normal life, with Alvin working at restaurants and at a carpet company.

But Alvin grew increasingly erratic and unreliable over time, Lola said. He drank, he dipped into drugs and was sometimes guided by irrational thoughts no one could fathom. He was a loner who disappeared for long stretches, came home, then vanished again.

“He had a prosthetic eye,” from an accident as a child, Lola said, “and he felt that people were looking at him or talking about him, even his own children.

“He would not admit that he had mental issues,” she went on, “and he was not going to try to get help because according to him, he was good. But if people knew what I went through and lived through, they would be amazed.”

The coroner’s office wasn’t open yet when Lola’s bus pulled into L.A., so we went to breakfast near Union Station. A few homeless people had congregated near the Denny’s parking lot, and while we ate, Lola Robinson eyed a dirt-crusted, manic, nearly naked man ranting outside.

We know, of course, that thousands of people in our jails and on the streets are mentally ill. Seeing the pain in Lola Robinson’s eyes reminded me that every one of them represents a family’s heartbreak and frustration. Every family wonders how it can be, in a civilized society, that sick people languish.

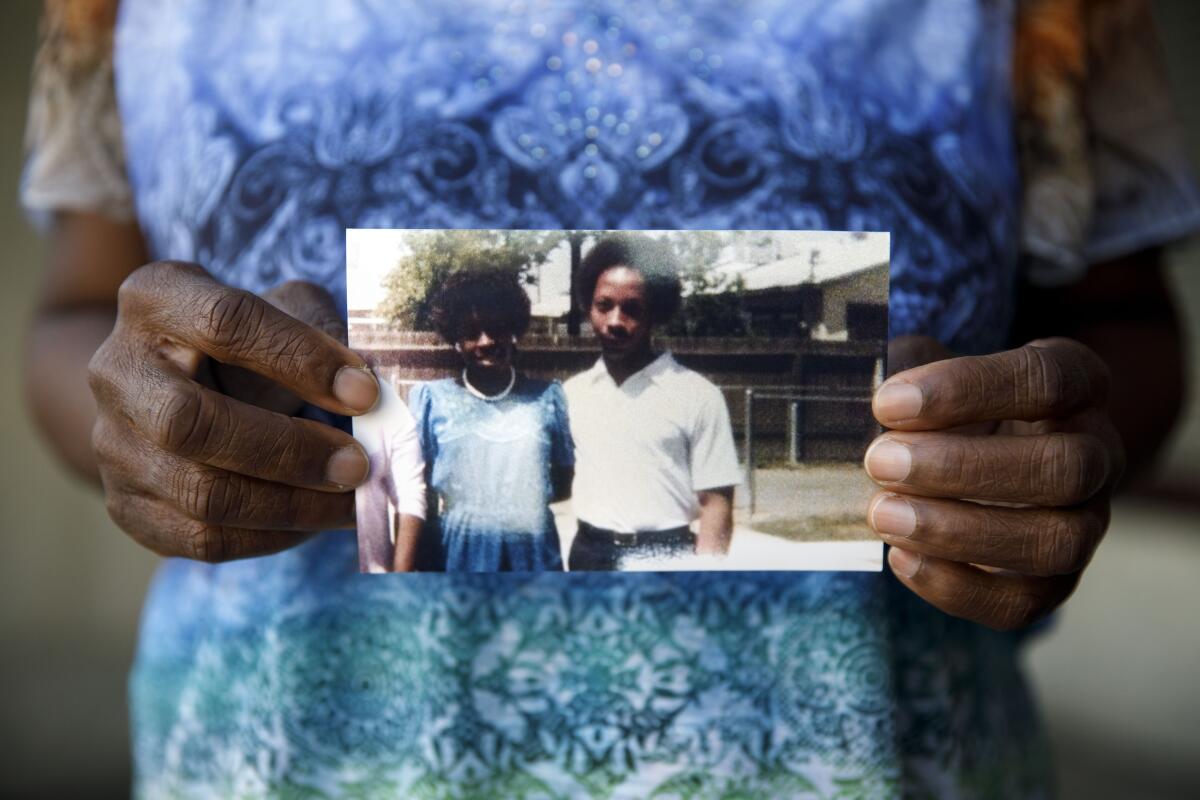

Lola Robinson showed me some family photos, including one in which she wore a fine dress, had just come from church, and was pregnant with their first child, Stephan, who is now 34. She wanted me to take a close look at the photos and tell her if I was sure that was the man I saw in West L.A.

She sagged when she heard my answer.

There were good times, she said, and happy moments. But she raised the kids largely on her own while working. She moved from Bakersfield to Las Vegas in 2004 and he came to live with her for nine months in 2006, when he had surgery for a leaky heart valve. Then he disappeared. She had not heard from him in more than 10 years when she got the phone call from the coroner’s office.

Lola Robinson had a rough start in her own life, which began in Modesto. She said mental illness ran in her family, and that she was regularly beaten with a hose while in foster care.

She dotes on her five children, her blessings, but lost a 2-year-old granddaughter to a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting. Her son Stephan was diagnosed with schizophrenia, had his own bouts with homelessness and was in and out of mental institutions. And Mrs. Robinson’s daughter has struggled to cope since being assaulted.

She carried all of these burdens without her husband’s help, and I asked whether she had ever resented him.

“I didn’t resent him because I knew he had mental issues,” she said. “I still love him. To hear that he’s dead, that’s devastating.”

Stephan was conflicted. He remembered horsing around with his dad, he said, then wondering where he was and finally getting used to his absence. The other kids had a range of views of their father.

“I told my son Justin, don’t be bitter,” Lola Robinson said. “Just forgive him because he had mental health issues, and I need your help to bury your father. He said mom, I’m not bitter. I’m just indifferent.”

She paused and added:

“I can’t leave him like he’s a nobody. I have to bury him the right way.”

An autopsy of Alvin Robinson did not reveal a cause of death, and the lab work could take 60 to 90 days. But in some ways, this is a relatively straightforward case for the Medical Examiner-Coroner’s office. Lt. Brian Kim, who leads an identification and notification unit, said it can take weeks or longer to identify someone who dies on the street.

Sometimes the bodies are decomposed, or there’s no ID on the person and no one in the vicinity knows the decedent’s full name. With Robinson, they were lucky: He had an ID in his wallet, and once they knew who he was, they were quickly able to locate his wife. It often takes a long time to find next of kin, and sometimes they’re never found. At the moment, Kim said, 97 next of kin notification cases are still open, and a lot of those involve homeless deaths.

Robinson’s story also illustrates how complicated it can be to address homelessness when a man with a mental illness or any other ailment refuses help.

In my view, the civil rights pendulum has swung too far in the wrong direction, providing an excuse for not intervening even when people are desperately in need of intervention. We stand by and watch, paralyzed, while people die of disease or addiction or both.

I told Mrs. Robinson I’m going to Italy this month to check out a model that Los Angeles is planning to try next year in Hollywood. In the United States, we closed mental hospitals without building the community clinics that were promised as replacements. Trieste, Italy, did build the clinics, and it built a culture in which the entire community is involved in rescuing and nurturing the lives of the most vulnerable.

She took a measure of hope in that, and in the thought that her husband’s death might help shine a light on the need for a better, more humane response.

At the coroner’s office, Lola Robinson wanted to see her husband, but viewings are not offered. A clerk wheeled her husband’s belongings into view.

“That’s a huge backpack,” said Stephan. “It’s probably everything he had to his name.”

The attendant then made copies of Alvin Robinson’s photo ID and gave them to his wife. For years, she had told me earlier, she had maintained her strength with God’s help. But seeing her husband’s ID nearly broke her.

She slumped and buried her face in her arms, and her body heaved as she let loose a stream of tears. Stephan put his arm around her and tried to comfort his mother, but that brought no relief.

“He’s in a better place,” Stephan said as his mother reached for a box of tissues.

It took several minutes for her to stand, still sobbing. She placed the copies of her husband’s ID into her purse, along with the photos that showed her family intact, in better times.

Lola Robinson began making arrangements a few minutes later for the cremation and a burial ceremony in Bakersfield. A few hours later, she and Stephan caught a bus back home to Las Vegas.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.