Winds drive California’s fire season. But people are what make it so dangerous

- Share via

California’s problem with wildfires is reminiscent of a line from the “Pogo” comic strip: We have met the enemy and he is us.

“The simplest formula is people equal fires,” said Bill Patzert, retired climatologist with the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Ninety-five percent of fires are ignited by humans.”

And those humans continue “building where we should not build,” said Char Miller, professor of environmental analysis at Pomona College. Sprawling subdivisions have added more fuel to what were already flammable, fire-prone landscapes.

“The fire danger has always existed as part of the geography and meteorology of the region,” Patzert said. Strong, dry Santa Ana winds have blown for millenniums, usually peaking between October and December, coming at the end of the seven generally dry months that precede about five wet months in California’s Mediterranean climate.

After months without rain, fuels — plants and plant debris from growth that sprouted and flourished after the relatively wet months — are bone dry and ready to burn. “Just in time for the Santa Anas,” Patzert said. “Every fall, it’s the great drama about which will arrive first: the wet season or the Santa Anas.”

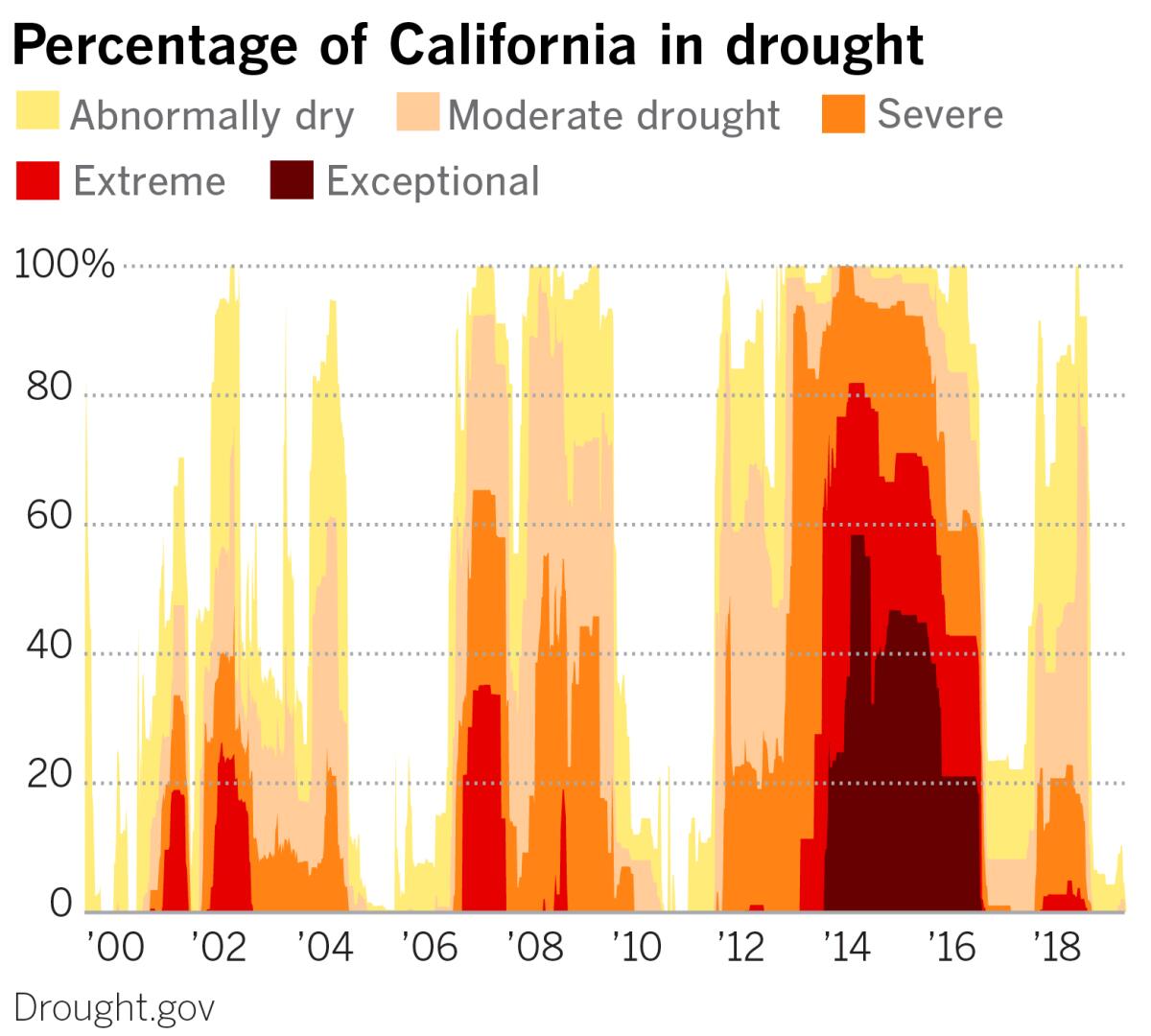

Since about 2000, California has been mostly in a drought. Wet and dry periods tend to be decadal events, Patzert said. The preceding period from 1978 to 1998 was mostly wet in California, but before that, the period from about 1945 to 1978 was largely dry.

These phases are related to what’s known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a recurring pattern of ocean and atmosphere variability in the Pacific basin. It’s kind of like a decades-long version of the El Niño-La Niña variation.

So droughts can be long “and tend to wax and wane,” Patzert said. “Not only that, they’re large, encompassing the entire Southwestern U.S.”

Miller agreed but added that the “whole Southwest has been in a drying trend since 1980,” citing a national climate assessment by the U.S. Global Change Research Program.

“Fire is normal, natural and historical in California,” Patzert said, “and we’ve ignored that.”

It’s a natural part of the ecology. Fire season has lengthened and the wet season has condensed with the prolonged drought. Starting in the 1950s, Smokey Bear has campaigned to prevent forest fires, but smaller, controlled fires are healthy and necessary for the forest.

Trees that are too dense compete with one another and end up starved for water. They are exploited by pests such as bark beetles, which have always been present in the ecosystem. The beetles are able to get the upper hand when trees are too tightly packed together and stressed for water. The trees lack sufficient protective sap, creating a chink in their natural armor.

“We’re victims of our own success,” Patzert said.

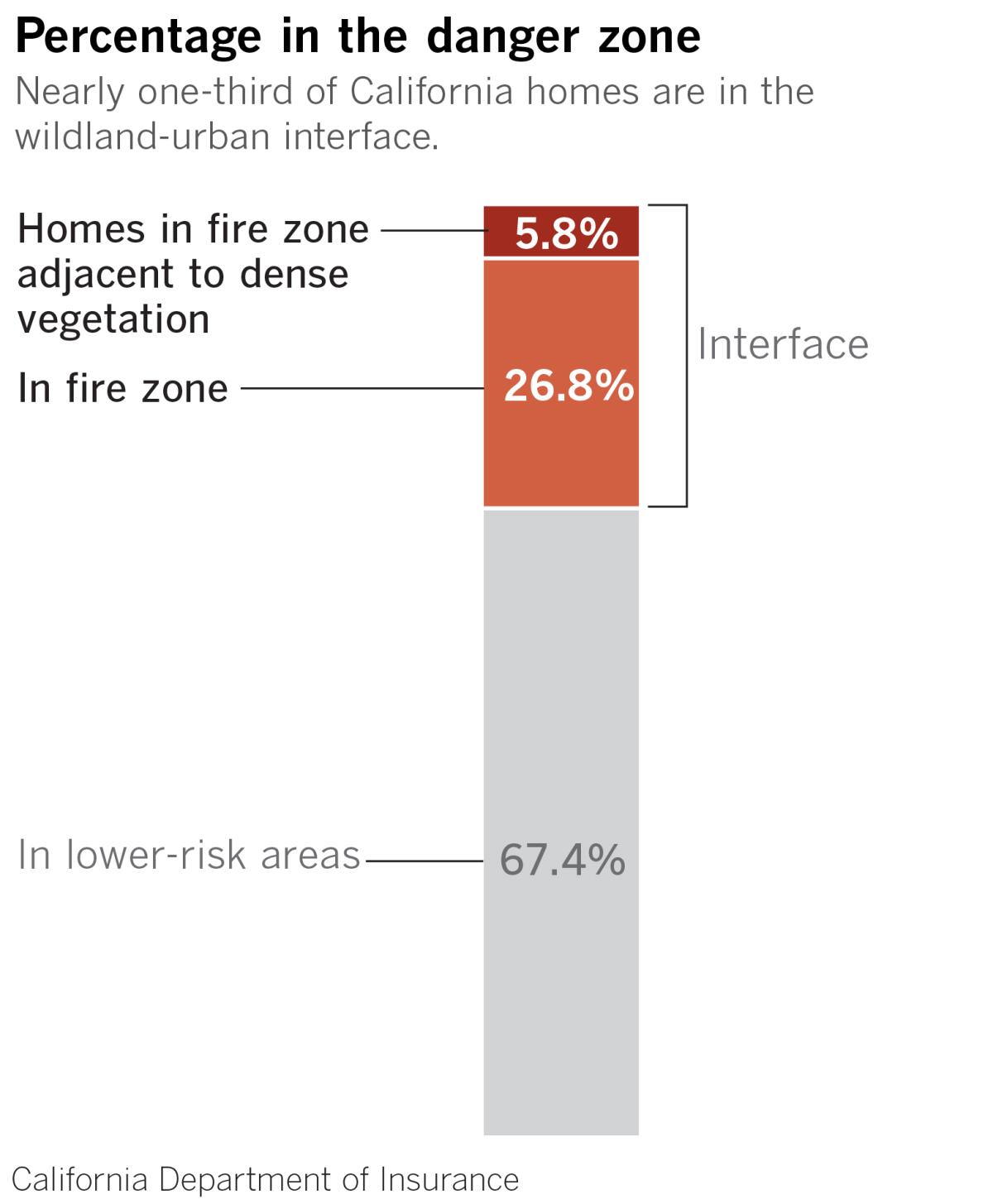

In the face of these facts and in the ongoing search for affordable housing for a growing population, Southern Californians have built in and adjacent to areas at high risk for wildfire. The housing most at risk is in trailer parks, where flammable individual units are close together. An example of the tragic result is the Sandalwood fire in Calimesa last week.

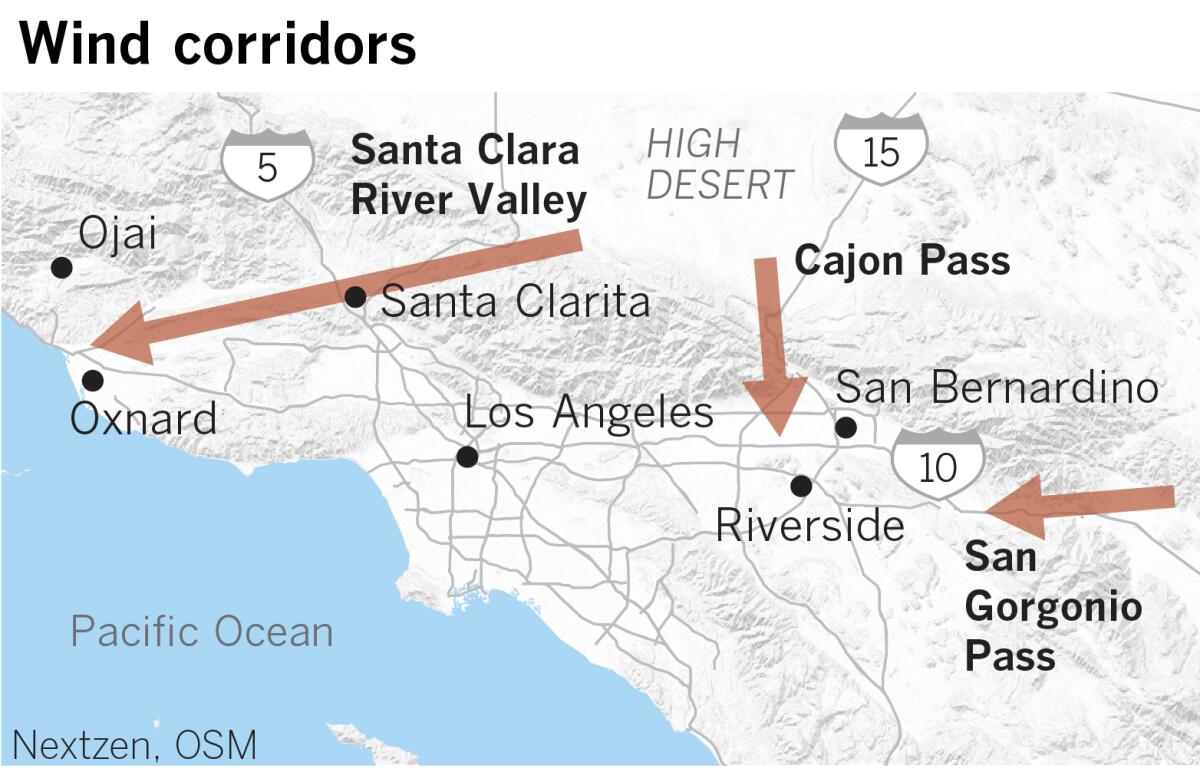

That fire burned near San Gorgonio Pass, also called Banning Pass. That’s the corridor that carries the 10 Freeway as it passes between the San Bernardino and San Jacinto mountains in Riverside County. The pass is a portal on the rim of the Great Basin and is among the most dangerous wind and fire corridors cited by both Patzert and Miller.

The other two are the Cajon Pass, through which the 15 Freeway travels, and the Santa Clara River Valley, which forms a wind tunnel-like corridor essentially connecting the high desert and the Santa Clarita Valley with the Oxnard Plain on the Ventura County coast between Oxnard and Ojai.

Toward the eastern part of that corridor, the recent Saddleridge fire was the third blaze near Sylmar in 11 years. Previously, the Sayre fire burned 11,000 acres in November 2008, and the monthlong Creek fire burned 15,000 acres in December 2017. That same month, the huge Thomas fire, at the western end of the Santa Clara River Valley, burned 280,000 acres in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties.

Wind farms have been established in both the Cajon and San Gorgonio passes, recognizing the near-constant winds in those areas.

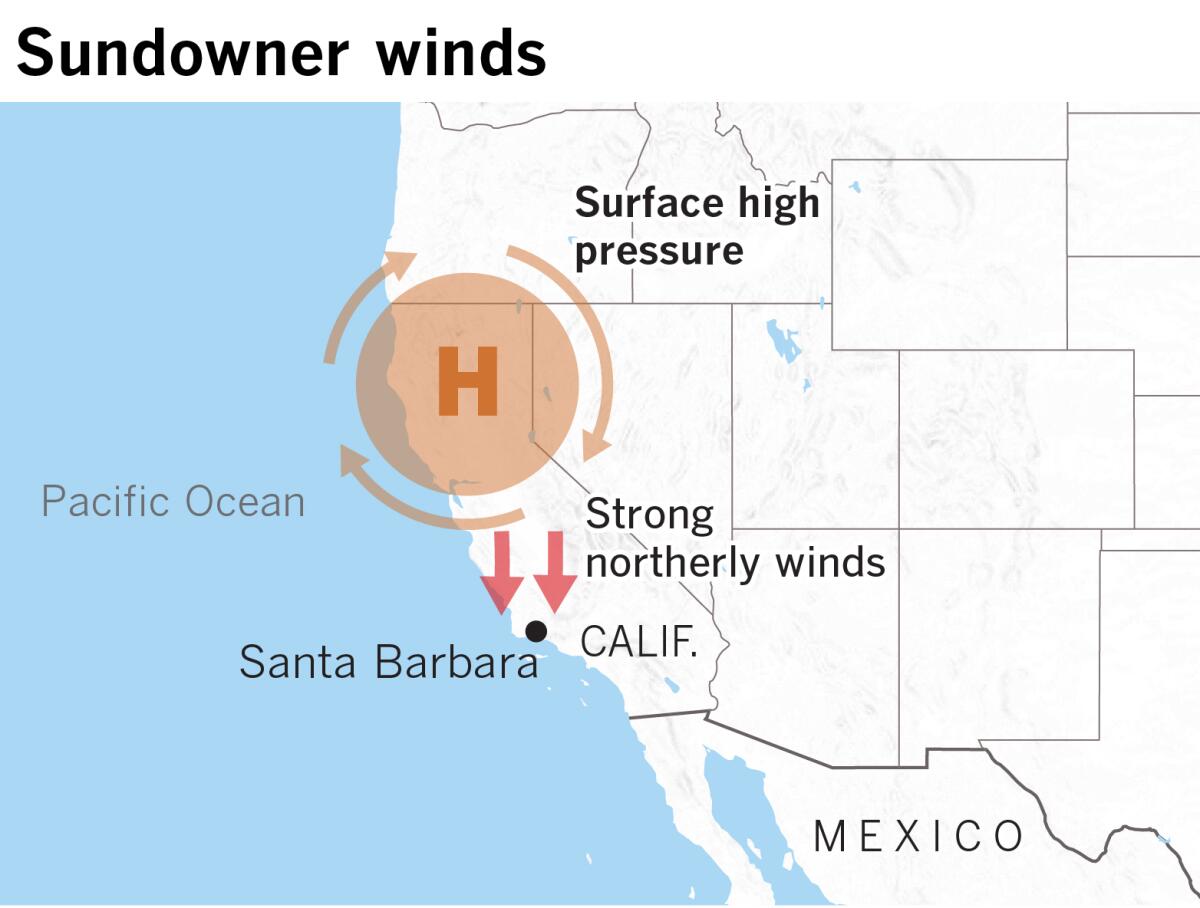

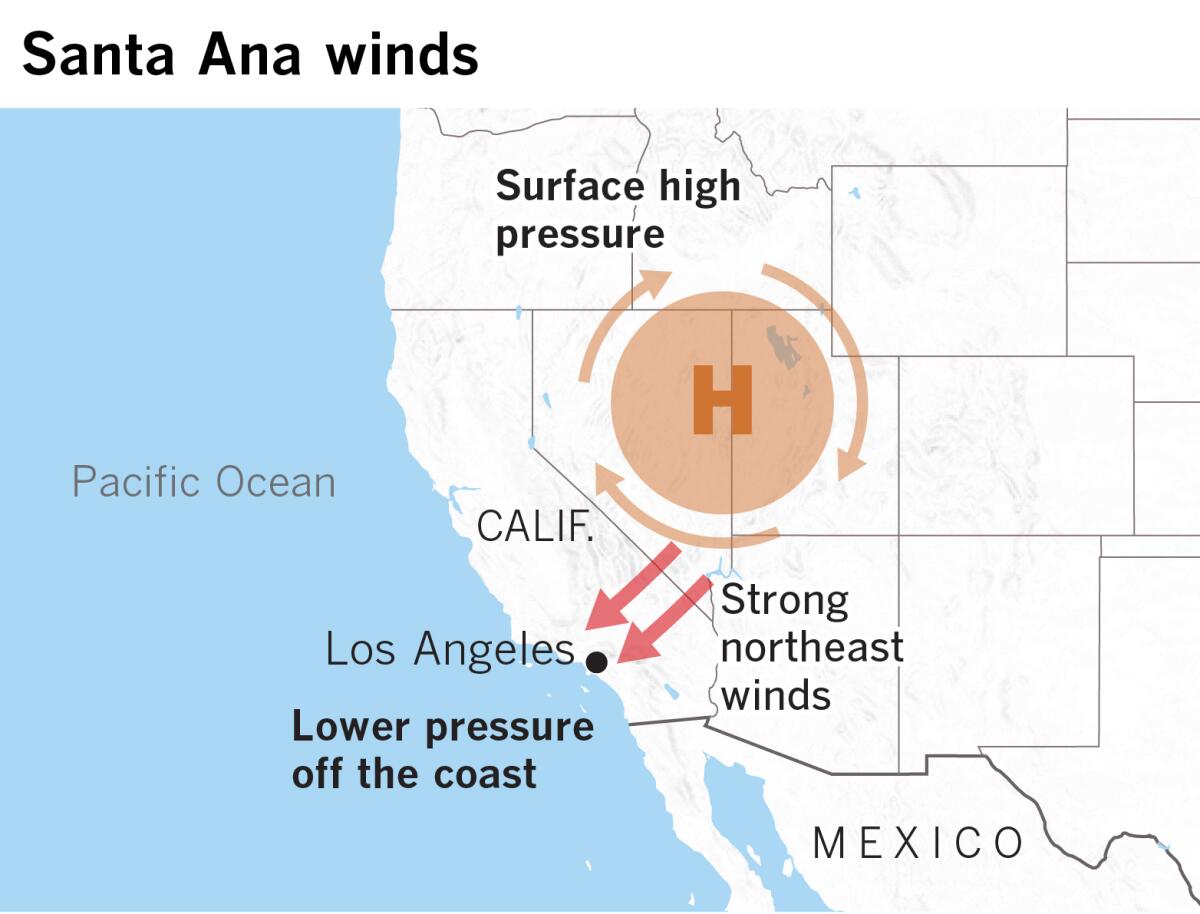

The typical setup for a Santa Ana event occurs when a surface high-pressure system moves east across California’s Central Coast. As it traverses the coast, its circulation generates northerly winds through every north-south canyon and pass in the Santa Ynez range of southern Santa Barbara County, and then through the 5 Freeway corridor immediately to the east.

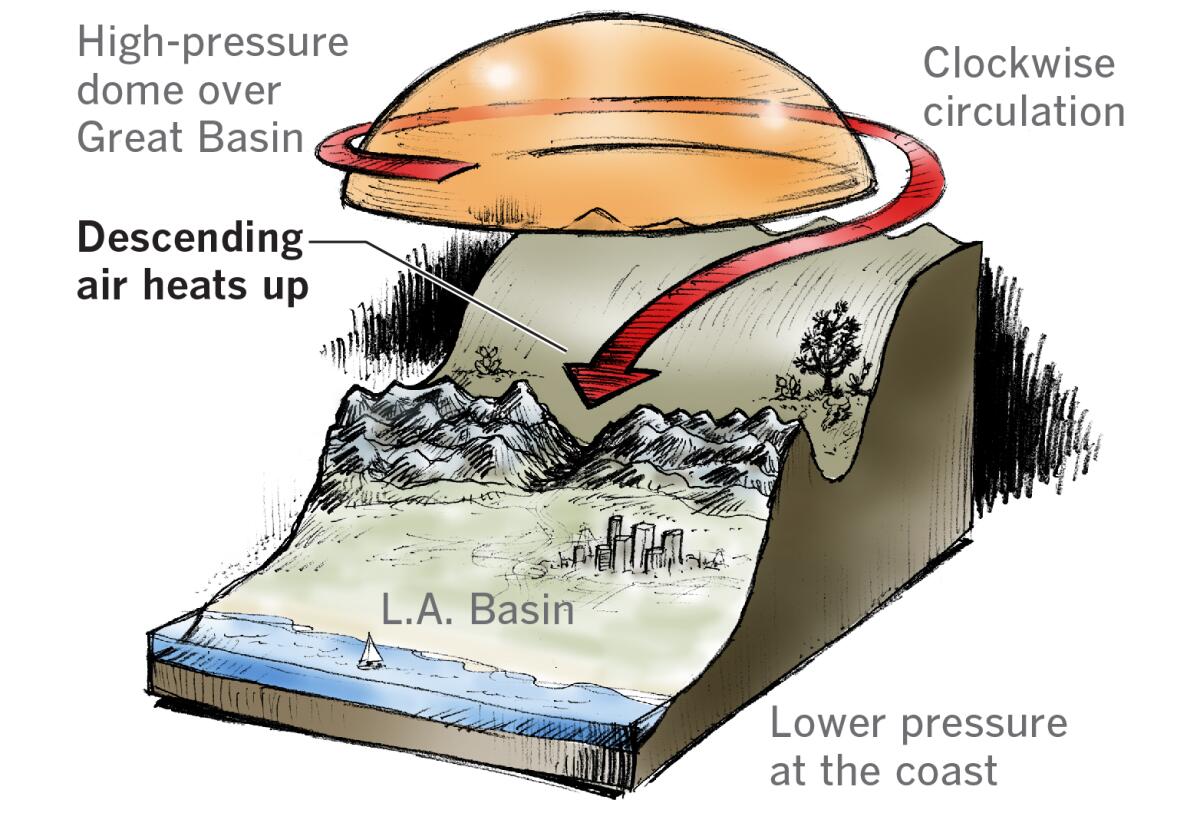

The high-pressure system then continues to move east and centers itself about 500 miles inland from Southern California in the Great Basin of central Nevada. There, it generates strong, dry, northeasterly Santa Ana winds. These are driven by clockwise circulation around the high-pressure system. Unlike low-pressure systems, which spin in a counterclockwise direction, with the strongest winds near the center — think of a hurricane — the strongest winds in a high-pressure system are in the periphery. These powerful winds blow across the high deserts of Southern California and through mountain passes, generating the “devil winds” that propel the Southland’s punishing fires.

Winds in high-pressure systems converge high in the atmosphere and have low humidity. As the air sinks toward lower pressure at the California coast, it is compressed and heats up. As the air warms, its moisture capacity increases, causing evaporation, drying out everything at the surface and further drying vegetation that is already dry by this time of the year.

As the downslope winds are pushed through narrow passes and canyons, they are constricted and speed up by what’s known as the Venturi effect.

Santa Ana winds are sometimes compared to a hair dryer. They suck remaining moisture out of fuel and can fan any spark into a raging inferno as efficiently as a blacksmith’s bellows. They also carry burning embers beyond a wildfire, spreading the inferno.

Climate scientists Janin Guzman-Morales and Alexander Gershunov of UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography have proposed that climate change may weaken high pressure in the Great Basin in the 21st century, pushing the Santa Ana season later, but persistent drought could keep California tinder dry with a wildfire season that stretches to year-round status.

Patzert sees the Santa Ana winds as but one small player in California’s fire story. Climate change is an existential threat to humanity, but the fire story is about so much more. It’s about where and how we live, disregarding the normal climate and wet-dry cycle, Patzert said. It’s about population growth and building in wind- and fire-prone areas.

Ventura County’s population, for example, has increased by a factor of seven since the 1960s and ’70s, Patzert pointed out. And most of that has been in a huge east-west fire and wind corridor that stretches all the way to to the Pacific Ocean.

In an op-ed piece in The Times, Char Miller called on local governments to stop greenlighting housing developments in fire zones and float bonds to purchase land in the wildland-urban interface to keep it out of harm’s way.

Who or what is responsible for the havoc of California’s ever-lengthening fire season? “Don’t blame the power companies and climate,” Patzert said. “That lets everybody off the hook.”

The evidence suggests that if we want to know who’s to blame, we need to take a collective look in the mirror.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.