California utilities — not lawmakers — are calling the shots on power outages to prevent wildfires

- Share via

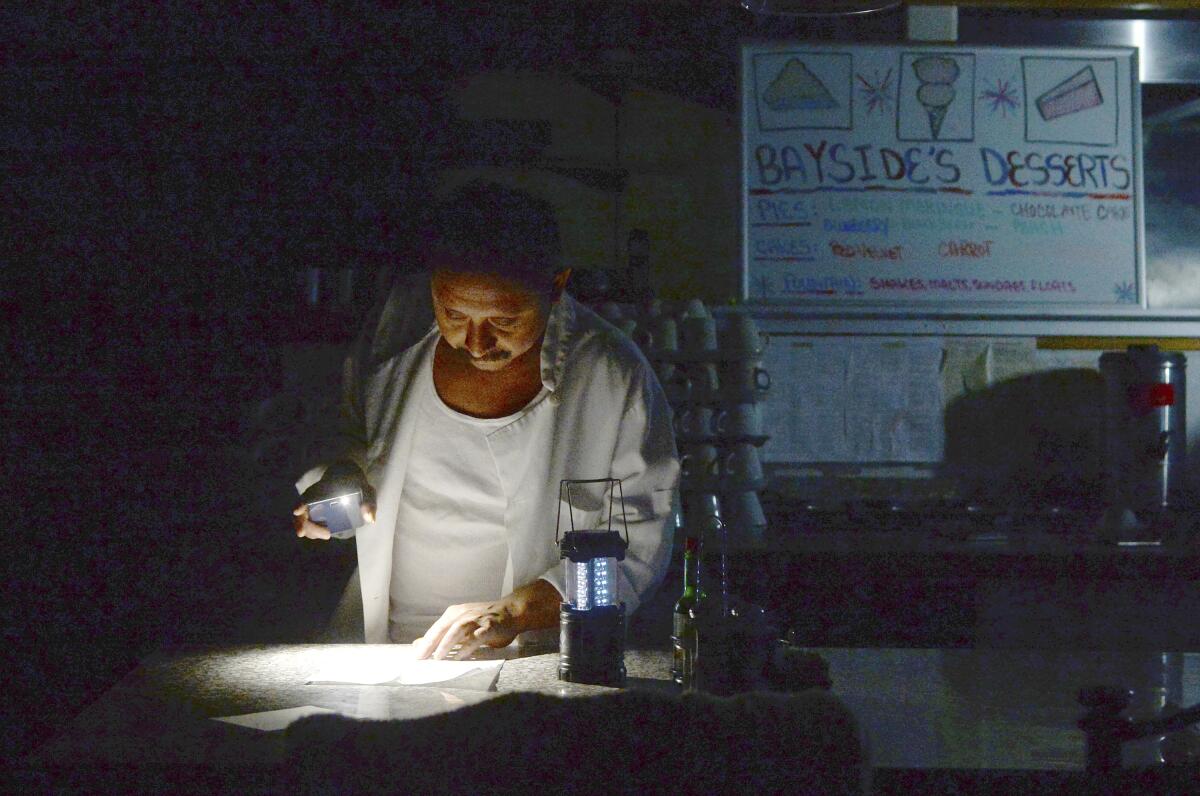

SACRAMENTO — The money wouldn’t have gone far to help Californians who needed to replace spoiled food, those who fled to hotels or shopkeepers forced to buy generators and fuel during the power shut-off by Pacific Gas & Electric Co. earlier this month.

Still, Gov. Gavin Newsom urged PG&E to do something symbolic: Give a $100 rebate to each of its frustrated residential customers and $250 to every business with no electricity.

“Lives and commerce were interrupted,” Newsom wrote on Oct. 14 to William Johnson, the utility‘s president and chief executive. “Too much hardship was caused.”

But last week, PG&E refused. And in doing so, what could have been a goodwill gesture became a symbol of defiance and futility: California’s investor-owned utilities may be criticized for their efforts at wildfire prevention, but they’re also calling the shots.

For a variety of reasons — the limits of existing regulations, the off-season for lawmaking in Sacramento, challenges in finding political consensus on policy — the status quo isn’t likely to change anytime soon. Millions of Californians can do little more than watch as the lights go off, then on and maybe back off again during the blustery autumn of 2019.

“This is simply unacceptable,” a visibly angry Newsom told reporters in Los Angeles on Thursday. “It is infuriating beyond words to live in a state as innovative and extraordinarily entrepreneurial and capable as the state of California, to be living in an environment where we are seeing this kind of disruption and these kinds of blackouts.”

In some ways, the disruption is by design. State officials have long known that in the otherwise highly regulated world of utilities, they have little control over what is known as a “public safety power shut-off.”

Existing rules state that utility companies have broad discretion over when and where power outages will be imposed. Neither the California Public Utilities Commission nor local governments have a formal role in the decision-making process. CPUC officials can only weigh in after power is restored.

The events Wednesday in Sonoma County, where an energized PG&E transmission line failed near what’s believed to be the origin of the Kincade fire, offer a glimpse at how subjective the decision-making can be. Company officials said Thursday that PG&E’s own forecasters believed wind speeds in the area would require turning off only distribution systems, not transmission lines. Johnson, who became chairman of PG&E six months ago, told reporters only that the utility uses “a formula or an algorithm” to evaluate historical data on winds and fire danger, but did not offer further details.

State regulators have established guidelines for the types of anticipated weather conditions that should prompt utilities to turn off electricity service and the warnings that should be issued before an outage. But many actions are left to the discretion of the companies, an opaque process criticized by state Public Utilities Commissioner Genevieve Shiroma during an Oct. 18 meeting.

“I keep coming back to the Wizard of Oz, where smoke and mirrors and this and that,” Shiroma told PG&E officials.

California’s other large utilities, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric Co., have the same relative autonomy over when and where to turn off power. Within 10 business days of an outage, a company must submit a report to CPUC officials explaining its decision to shut off power, including information on weather conditions in the outage area.

The report must include details on the types of customers affected and the advance notice they were provided, the location and duration of the shut-offs and an accounting of any wind-related damage to company equipment.

Regulators are supposed to use the report to determine whether the outage was reasonable. But the documents often provide only summary information, making their value unclear. Though CPUC officials can penalize companies for how they carry out wildfire-prevention blackouts, they never have. Even then, an administrative law judge would decide such a case under a process that could take several months.

Only the California Legislature can strengthen the CPUC’s power over utilities. And reaching consensus on expanding the agency’s operations could be tough — it has struggled with oversight of a vast and varied portion of the state’s economy, including electricity, telephone service, ride-hailing and limousine companies.

Even if lawmakers want to do something now, they can’t. The Legislature has adjourned for the year and isn’t scheduled to reconvene until January. The only way to engage more quickly is to convene a special legislative session.

History offers a lesson from California’s last energy crisis of almost two decades ago. In December 2000, then-Gov. Gray Davis promised to convene a special session to draft plans to help the state’s utilities. One key proposal — requiring the state to sign long-term energy purchase contracts with major utilities — went from introduction to law in just a month. Additional efforts to address the causes of the widespread blackouts were put in place that spring.

Laws passed in a special legislative session, even those requiring a simple majority vote, take effect 90 days after the end of the proceedings. Similar bills in a regular session don’t become law until the next calendar year. And unlike in 2000, when an election had just taken place and lawmakers had yet to take the oath of office, California legislators this year are in the middle of their terms and appear more inclined to act. Varying ideas have been floated, including incentives for clean energy that can be locally stored for broader outages and a broad investment in “microgrid” technology to better isolate power shut-offs to communities where fire danger is most extreme.

Action could be swift at the state Capitol, but only if Newsom convenes a special session.

So far, the governor has sounded unconvinced.

“To the extent that’s necessary, I would be open to it,” he told reporters in Sacramento on Oct. 17. “But in the absence of the necessity, I’m not sure. I think it’s more symbolic benefit than a substantive one.”

That leaves lawmakers few options other than convening informational hearings. Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) said Thursday that a “working group” would study blackouts, comprising state senators from many of the communities hit hardest. Atkins also announced a public hearing on the issue to be held next month, just days before Thanksgiving and probably after dangerous fire conditions have dissipated.

The state budget that legislators approved and Newsom signed in June sets aside $75 million to offset the effects of mandatory blackouts. Half of the money will be spent by state officials to ensure government services aren’t disrupted, with the rest allocated to grants to help affected communities purchase generators or other energy backup systems. But state officials haven’t said whether the money will provide widespread help over the coming weeks.

Perhaps the most difficult part of what happens next is deciding who ultimately bears responsibility with the public for the blackouts. The governor wrote to each of the state’s major utilities on Thursday to complain that they haven’t fully kept state emergency services officials in the loop on outage plans.

“They better step up,” he said of the utilities on Thursday.

But the key players, including Newsom, undoubtedly realize the danger in being seen as decision-maker when lights are turned off or homes and businesses are destroyed by utility-sparked wildfires. Johnson wrote in a letter to the governor last week that the state should consider taking over the responsibility of making the final determination when to shut off the electricity.

Newsom, who told reporters just last week that his advisors had considered the effects of broader government control over power shut-offs, rejected the idea after touring firefighting operations in Sonoma County on Friday and lashed out at the state’s most embattled utility.

“It doesn’t surprise me that PG&E is looking for a bailout,” Newsom said of the now-bankrupt company. “We will not bail out PG&E.”

Times staff writer Phil Willon contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.