Only two months into pursuing his dream to be a sound engineer, David Gross knew he’d made a mistake.

The single father in 2013 signed up at a for-profit college in Burbank that convinced him it was his path to a Hollywood job. But after two classes, he realized it was “definitely not what I was promised,” he said.

Gross took a leave of absence. But before he decided whether to return, the U.S. Department of Education forced the school, Video Symphony EnterTraining, to close after an investigation found altered records and thousands of dollars in missing financial aid money.

Five years later, Video Symphony, now transformed into a debt holding company, took aim at Gross. It sued him for $14,000 — the amount covering almost eight months of the program that it says Gross attended, and including federal loan amounts the government refused to give the school after the allegations of misconduct.

More than 500 lawsuits have been filed against the school’s ex-students by Michael Flanagan, the educator-turned-debt collector who owned Video Symphony. He says students signed binding contracts and are obligated to pay.

“This is not money you were getting for free,” Flanagan said in a recent interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Demonstrate that you don’t owe the money and we will certainly revise and drop or reduce the demand, but essentially every single person here owes the money.”

Students and legal experts say the cases are more complicated. They claim Video Symphony broke its end of the deal by not providing the education it advertised, letting them believe they were receiving federal aid when they weren’t and failing to keep accurate records.

The story of Video Symphony highlights a larger problem with regulation of for-profit colleges and the aftermath when they fail, say legal experts: No level of government, from local prosecutors to federal and state education officials, has enough interest or responsibility to examine these cases.

For the record:

11:11 a.m. Jan. 22, 2020Michael Flanagan, the owner of Video Symphony, disputes that former student David Gross attended the school for two months. Flanagan said Gross attended 22 classes during an eight-month period. Additionally, Flanagan said Gross had an option to finish his degree through an arrangement with a similar for-profit college and disputes that he received federal financial aid.

In California, oversight of for-profit colleges and student loan debt remains convoluted and unreliable, despite years of reforms. Its patchwork nature has left each student to fight their own battle in a limited debt collection court that lacks the jurisdiction to look at the complaints collectively.

The result, said multiple legal experts familiar with the cases, is that Flanagan has won many lawsuits — collecting more than $300,000 — when students attempt to represent themselves or fail to show up at court, a common occurrence for those without legal savvy who don’t understand that not being present means losing.

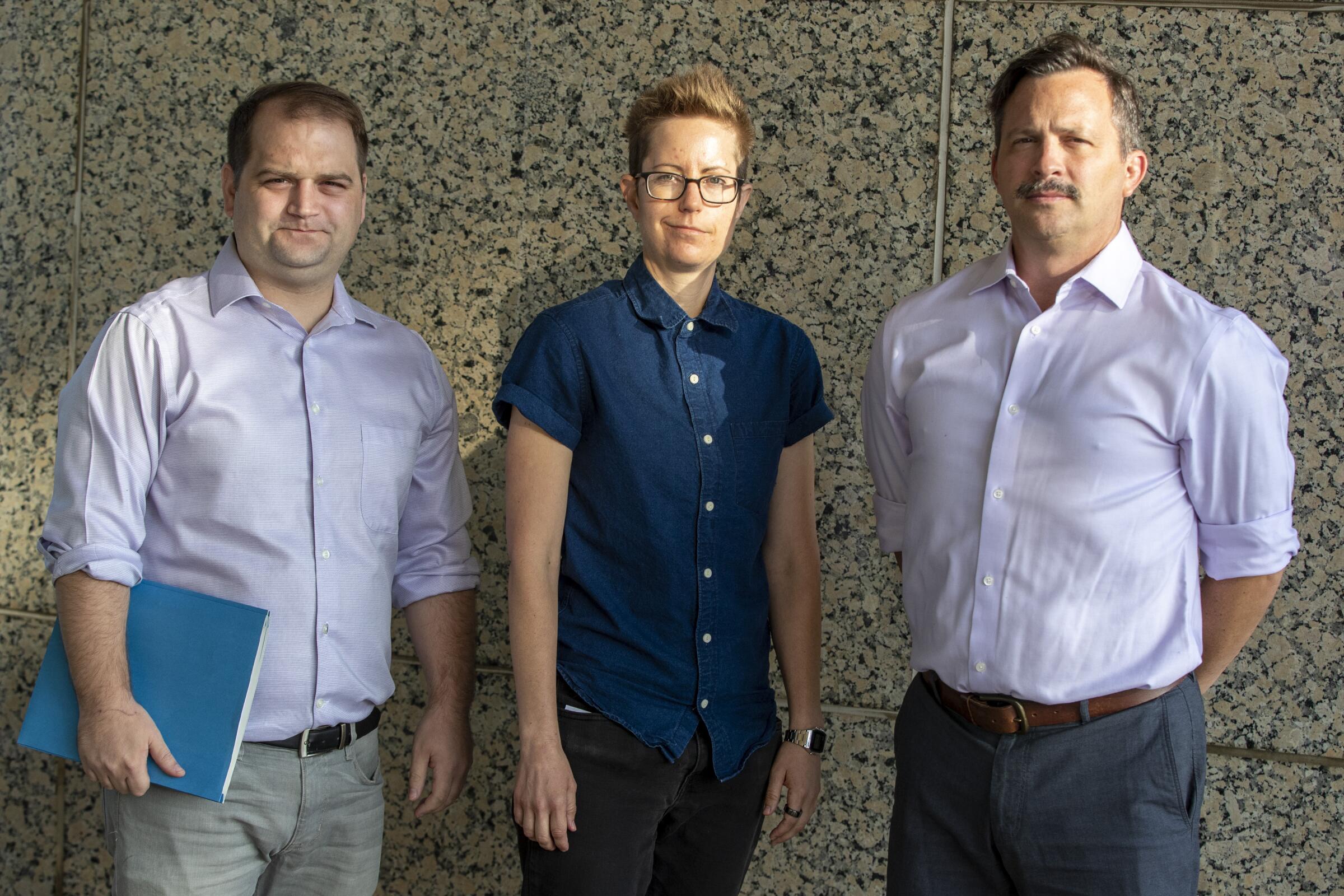

Robert Muth, managing attorney of the Veterans Legal Clinic at the San Diego School of Law, has successfully represented two veterans sued by Video Symphony. He said the lack of scrutiny by authorities is “surprising.”

Attorneys at Public Counsel, a Los Angeles nonprofit legal firm that has successfully defended several Video Symphony students, have argued in court that there may be issues of fraud if the cases are viewed as a whole. Like multiple attorneys who have defended Video Symphony clients and spoke with The Times, they believe the lawsuits should be examined by state or local prosecutors, who have the ability to file civil actions on behalf of residents.

The Times found that the offices of Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey and state Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra were contacted about Video Symphony, but so far have taken no action on behalf of the students.

Lacey’s office referred students to Public Counsel. Becerra’s office declined to comment on Video Symphony, issuing a statement that it was “deeply disturbed by the lack of accountability of for-profit colleges” in general and “focused on system-wide fixes.”

Large-scale for-profit failures such as Corinthian Colleges, ITT Tech and L.A.-based Dream Center schools have received such scrutiny from public prosecutors for similar complaints — though the financial stakes were higher.

In 2013, then-Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris filed a civil action against now-defunct Corinthian Colleges on behalf of its 27,000 California students. Investigations found the school used deceptive marketing and unfair debt collection practices. Harris won a default judgment that required Corinthian to pay more than $800 million in restitution to students. Becerra has also weighed in on high-profile failures and the resulting debt, including an ongoing civil suit against Ashford College, an online for-profit owned by a San Diego company.

Prosecutors are meant to be the last line of defense for for-profit students in California, though. Another source of frustration for those familiar with Video Symphony is the track record of a key state regulator, the California Bureau for Private Postsecondary Education, a troubled agency whose future will be debated by legislators in coming months. The agency is charged with investigation and oversight of the state’s 700 for-profit colleges, which cater largely to low-income people, veterans and students of color.

The bureau was informed by accreditors and the U.S. Department of Education of problems at Video Symphony in 2013. It inspected the school and cited it for record keeping problems that year, documents obtained by The Times show. But students say the bureau didn’t follow up as the school spiraled down to ensure they were informed about rights, including loan forgiveness.

While the bureau has little jurisdiction over closed schools, documents The Times obtained under the California Public Records Act also show the bureau knew about the lawsuits in 2016 and was concerned enough to request a list of students being sued from Flanagan. But it does not appear to have taken further action — the veteran who filed the complaint, Robert Harden, said he never heard back from the agency. The bureau declined to comment on whether it had ever investigated the school.

Michael Peck, a former Video Symphony student being sued for $16,000 he claims was awarded to him as grants and tuition discounts, said he believes the cases are “the shadiest thing ever,” but needs “someone to help the students figure out what’s going on.”

Flanagan disputed that any of the cases are unjustified. He said Gross is misrepresenting the amount of time he attended, and disputes Peck was given what amounts to half of his tuition as discounts or grants.

“This is money you have to pay back,” Flanagan said.