How to spot fake coronavirus news on social media

- Share via

Bad information about the novel coronavirus appears to be contagious. But there are some steps you can take to verify information on social media before you share it.

The temptation to share unverified but alarming information is understandable. Many of the people who share hoaxes don’t do it to mislead; they think they’re sharing valuable information with their friends and family. But it’s easy to hit “retweet” on something that’s just not true. And false information isn’t helpful to anyone.

For the record:

2:52 p.m. March 26, 2020A previous version of this article misstated a French doctor’s erroneous advice; he advised people against taking ibuprofen, not Tylenol. Since he made those statements, however, experts have said either drug is fine to help reduce fever in people with COVID-19.

“We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic. Fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus and is just as dangerous,” said World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Feb. 15.

For starters, if someone high up in the government or military was attempting to communicate vital information to American citizens, they probably wouldn’t do it with a rambling screenshot from the Notes app. A source in Homeland Security is not trying to get the word out about impending martial law, and there is no “high-ranking military friend in D.C.” passing along a tip about the president using the Stafford Act for a nationwide quarantine.

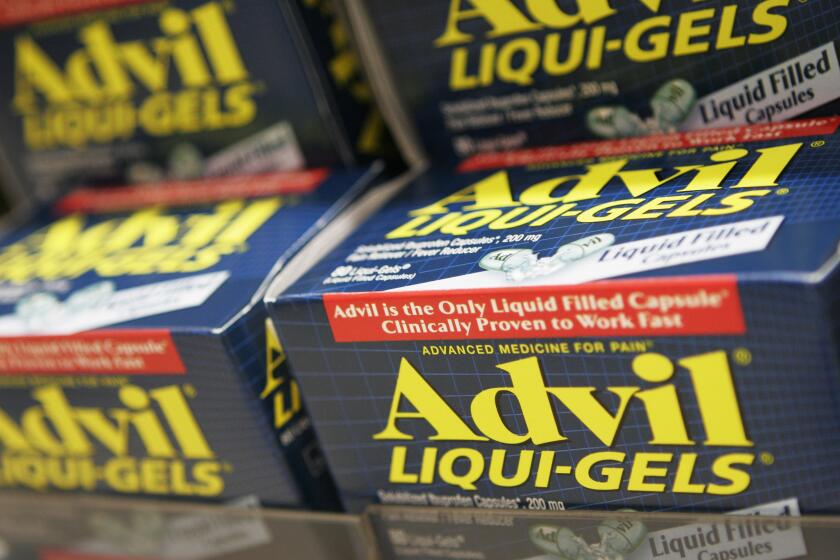

Another hot topic: ibuprofen. The French doctor who originally advised people to take Tylenol probably meant well, but medical experts around the world say there’s no evidence ibuprofen is linked to a higher risk of COVID-19 infection, nor has it been linked to increased complications from the disease.

Ibuprofen is not linked to a higher risk of COVID-19 infection, nor has it been linked to complications in those infected with the novel coronavirus.

President Trump, no stranger to repeating rumors that would reflect well on him, has repeatedly claimed that certain existing drugs could treat coronavirus. Elon Musk shared that optimism. But while scientists are working to test the efficacy of the malaria drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in fighting coronavirus, there’s currently no reliable, published, peer-reviewed evidence on the subject. The Food and Drug Administration has not approved either drug to treat the disease, and no one should be attempting to self-medicate with it. Already, this bad information has had tragic repercussions: A man reportedly died after ingesting chloroquine at home in Arizona in hopes of preventing coronavirus.

So take a beat before you retweet. Here are some ways to verify what you’re reading before you share.

Verify the account that’s posting the information.

- Check the account. Are they verified on Twitter or Facebook? That lends more credibility to what they say. If they aren’t verified, do more checking.

- Check the photo on the account. Does it seem like a real person, or is it a photo of a celebrity or something generic, like a sunset or a flower? You can use reverse Google Image search to see if the photo was taken from elsewhere on the internet.

- Check the age of the account and how many followers it has. A brand-new account with a dozen followers is unlikely to be one that’s breaking major national news.

- Scroll back through some older posts — has the account always shared news, or was it a meme account a month ago?

- Take note of how the news is being presented to you — just in the tweet? Is there a link to a longer story somewhere? Again: A screenshot of an email, text message, Google Doc or Notes app is unlikely to be good information.

- Check the source. Is the account attributing the information to an organization, a politician, a news outlet, or “a friend of a friend”? Good information will have a reputable name to back it up.

Hoax emails and messages, including those about martial law and the Stafford Act, are as dangerous as the coronavirus itself, health officials say.

Verify the site the information is coming from.

- If there’s a link, click it. Does it go where you expected it to go? Check the URL — are you really on the site you think you’re on, or does something seem off? Look for strange spelling and anything weird in the web address.

- A website you’ve never heard of is unlikely to be the first and only source for major breaking news, no matter how slick the layout looks.

- Check the date on the article. Is it new or old?

- Check the byline. Is it a real name? Click through to the bio page — does it sound real? Does the author have social media accounts where you can verify that he or she is an actual reporter? This is another opportunity to use Google Image reverse search if there’s a photo.

With so much false information circulating about the coronavirus outbreak, health officials are trying to set the record straight. Here’s why that can backfire.

Verify the information itself.

- The best way to verify a piece of information is to see whether reliable news outlets have reported it. As news organizations, there is a burden on us to do more digging to verify things before we share them on social media. We don’t always get it right, but there’s a better chance something tweeted from your local newspaper is true than something from a completely random person with no accountability to anyone.

- Read the story or post. Does the wording sound off — maybe like it was run through Google Translate a few times? That’s one way fake news websites rip off articles from legitimate sites.

- Trust your gut. If there’s a nagging voice in the back of your head saying, “Eh, I’m not entirely sure this is true,” or “Wow, that sounds kind of far-fetched, but who knows?” it’s better to hold off on sharing it until you can verify.

If you see someone on social media sharing information that’s not true, try to be gentle when pointing it out. Correcting false information can backfire. People are prone to be defensive and to double down when they’re challenged. We’re all a little tense right now. Be kind. And don’t forget to wash your hands.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.